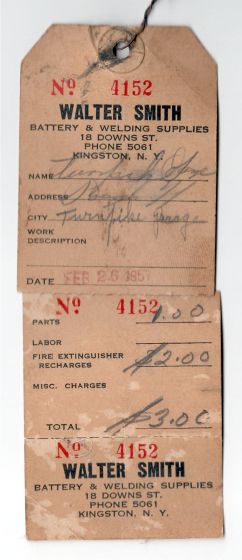

Well, a shattered lens found beside the road on a walk:

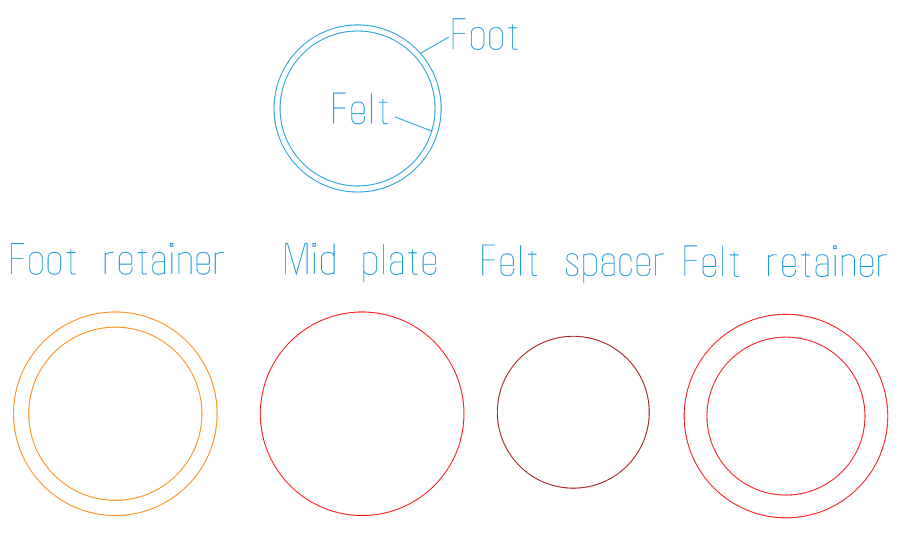

The battered frame has enough information to suggest they were once rather fancy. At this point, all that matters is they have two glass layers separated by a dark plastic polarizing film, with a gold-ish metallized front glass surface.

I fired the two pulses (on the left side of the obvious crack) at the front of the lens, both at 100 ms / 70% power:

Neither pulse penetrated the lens.

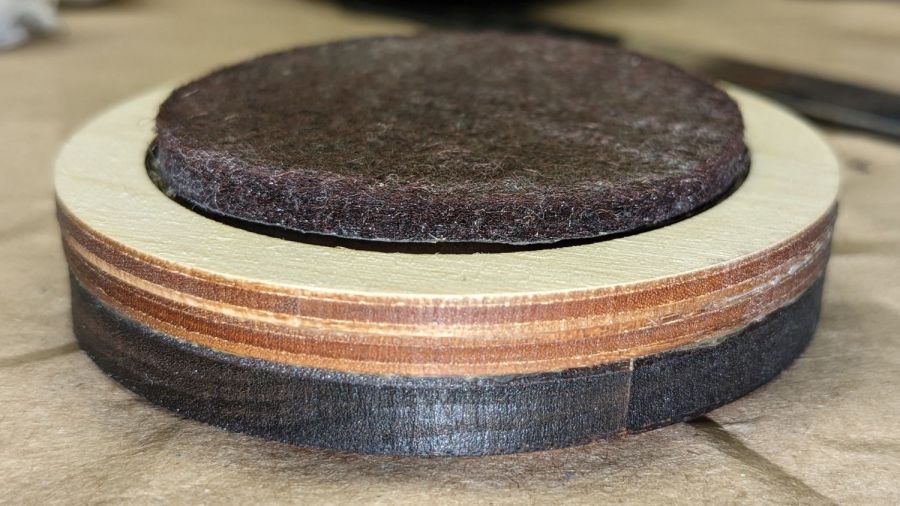

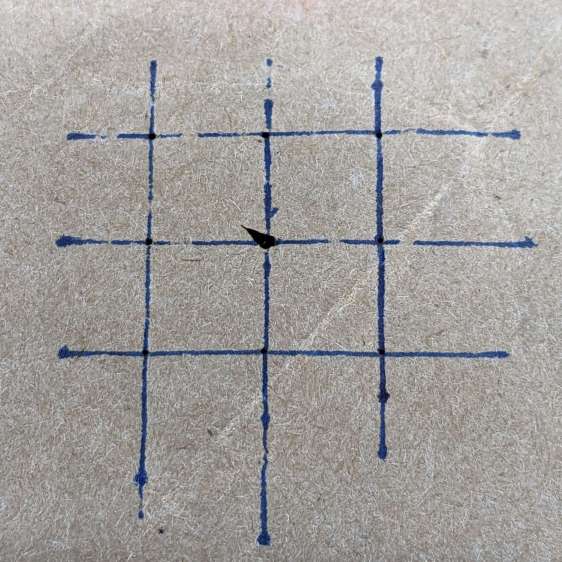

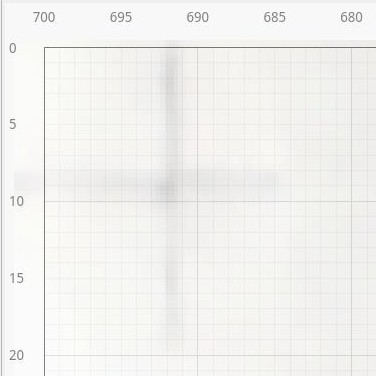

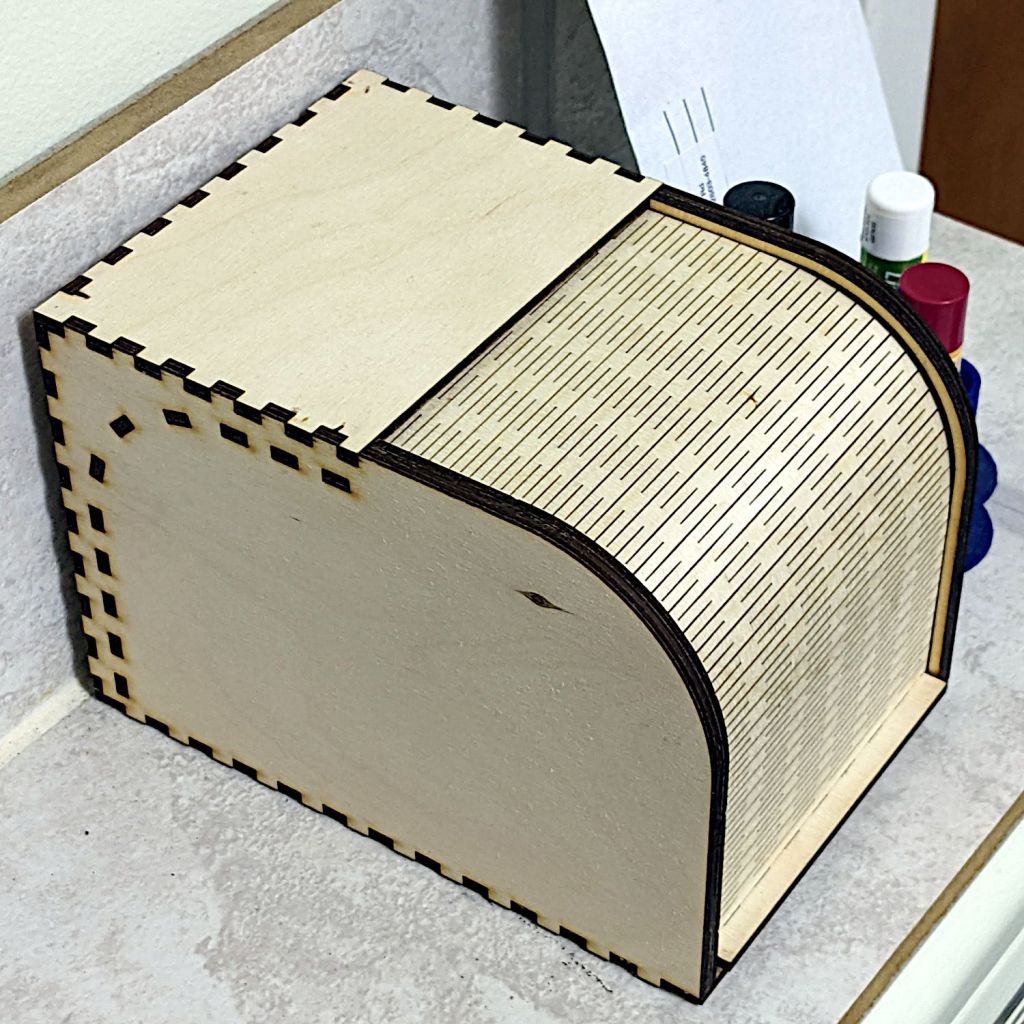

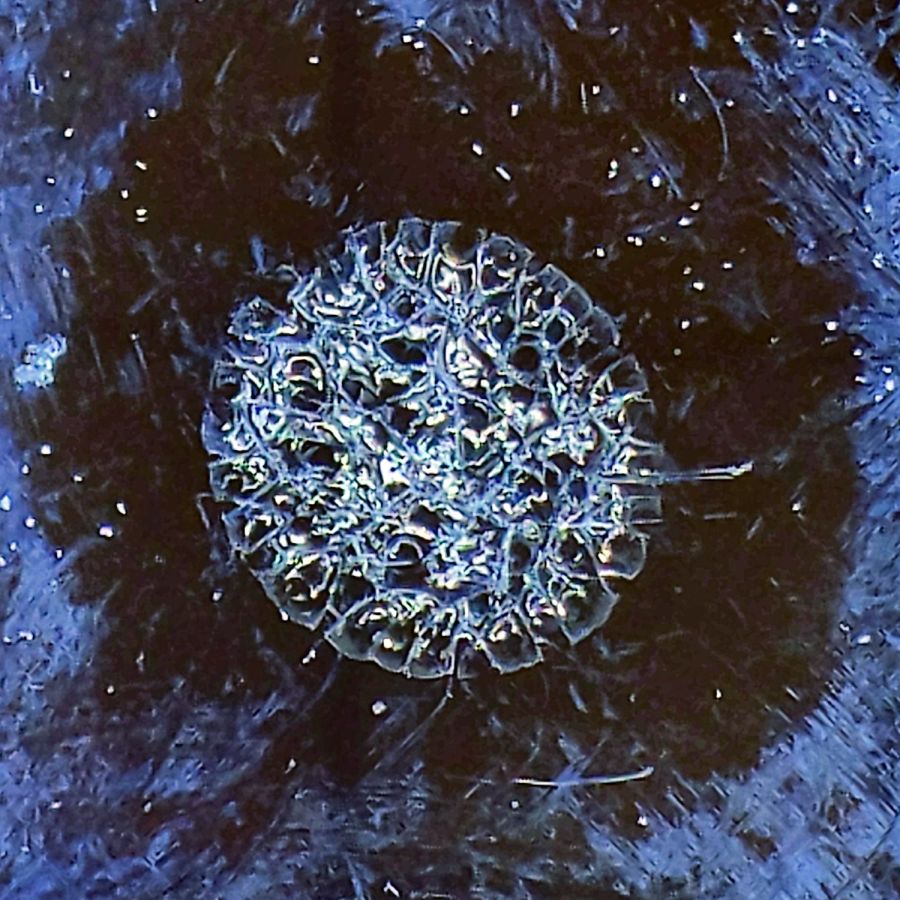

The smaller zit was fired in the position shown in the first picture, with the focal point more-or-less at the top surface of the lens. As seen from the front:

The outer part of the damaged area is about 0.5 mm in diameter. The heat around the damage seems to have cleared away all the schmutz on the lens; those things that look like scratches are oily smears and road dirt.

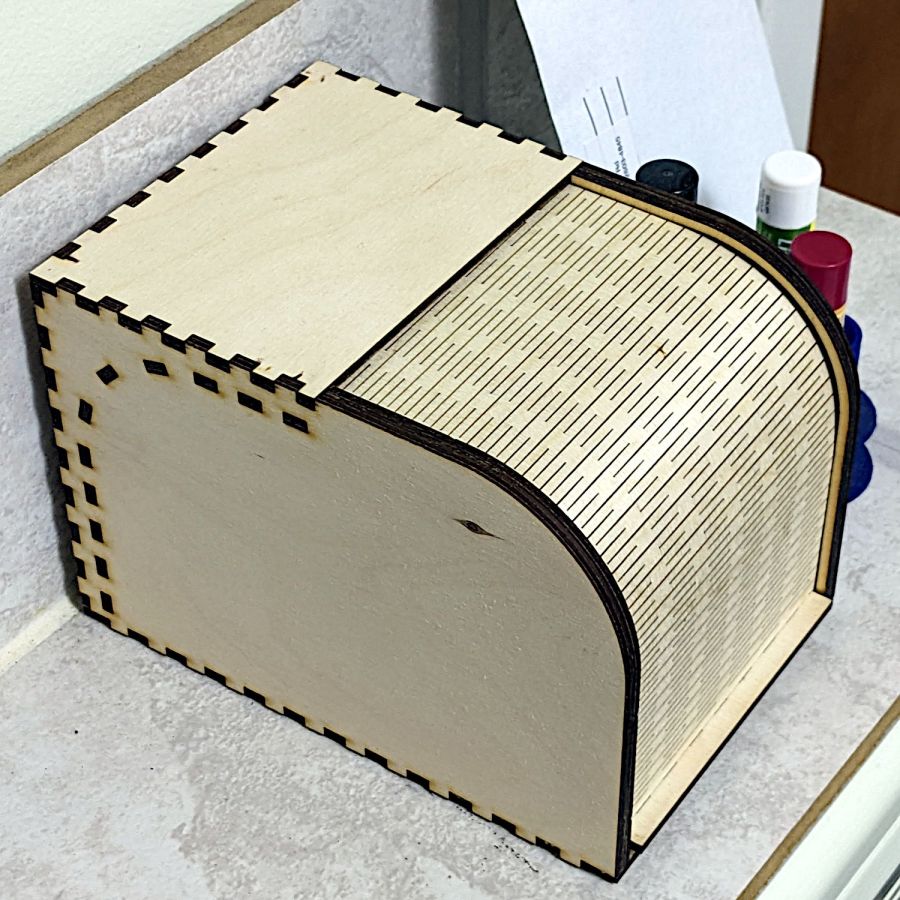

Seen from the rear:

The rear surface is blistered, but doesn’t have a hole, so I think the beam melted the glass and inflated a cavity along its path.

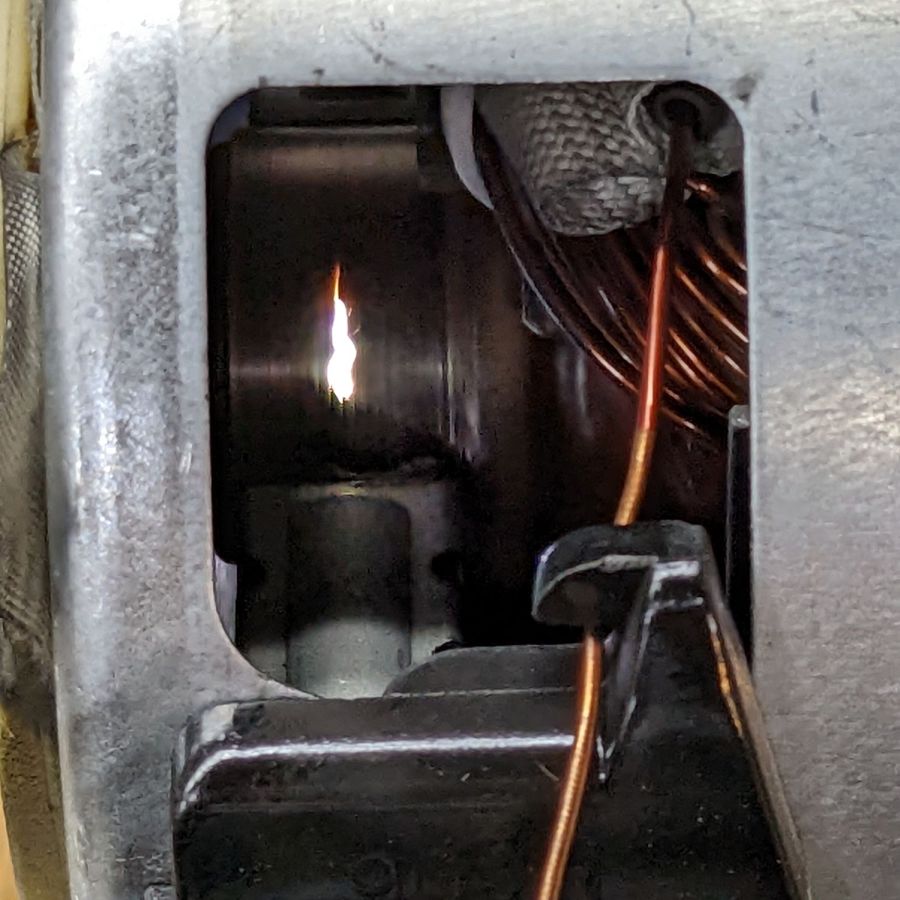

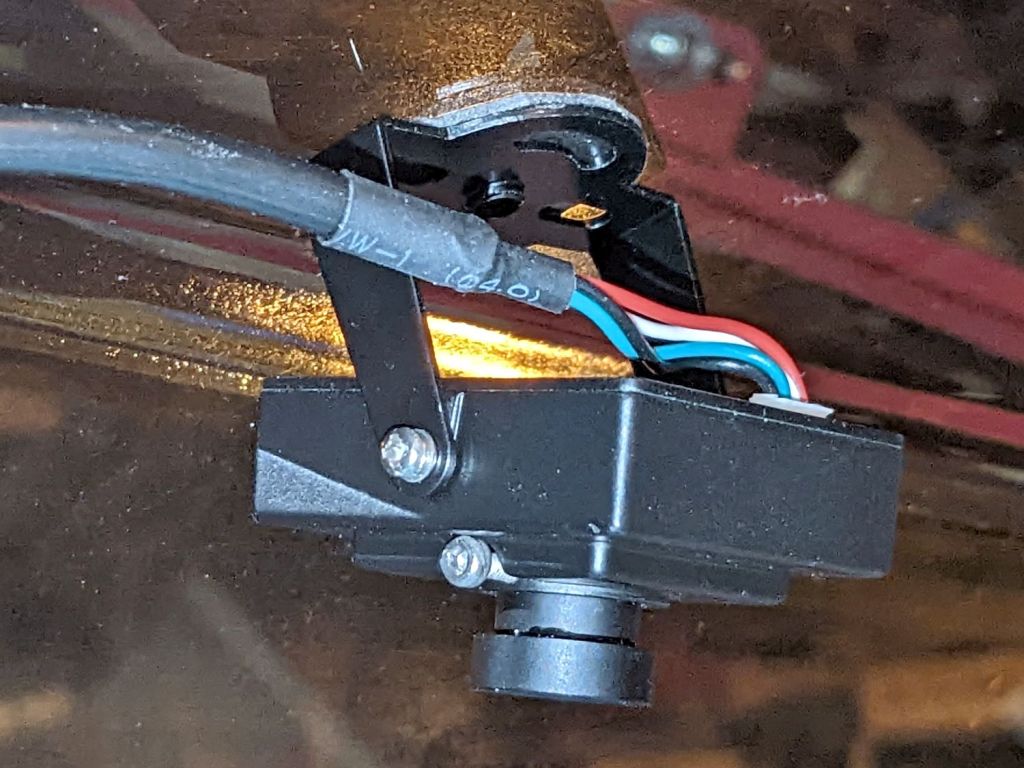

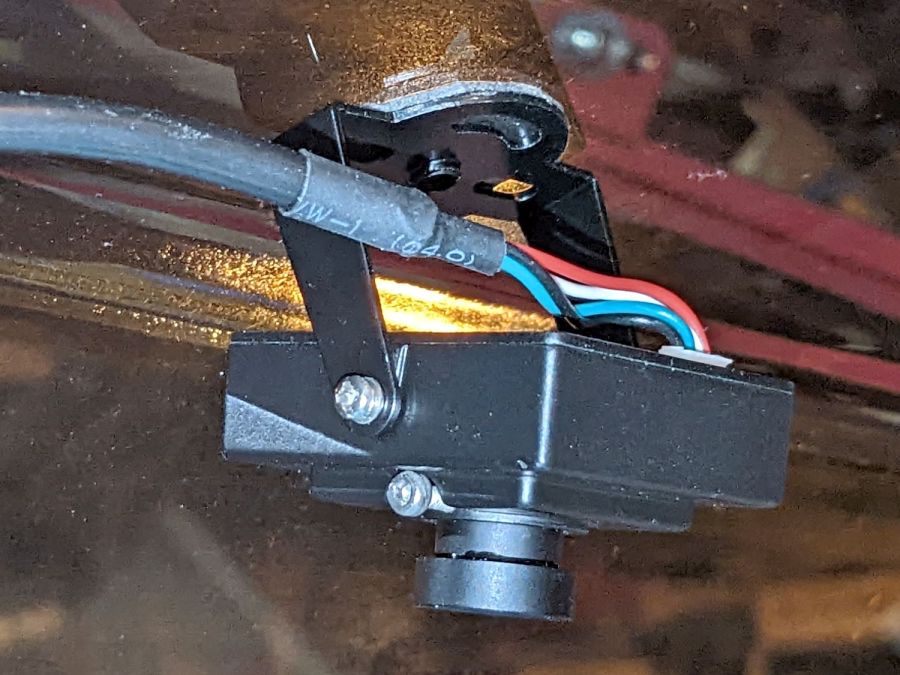

I then perched the lens in the unfocused beam path, with paper taped over the laser head opening to keep any fragments off the mirror and focus lens:

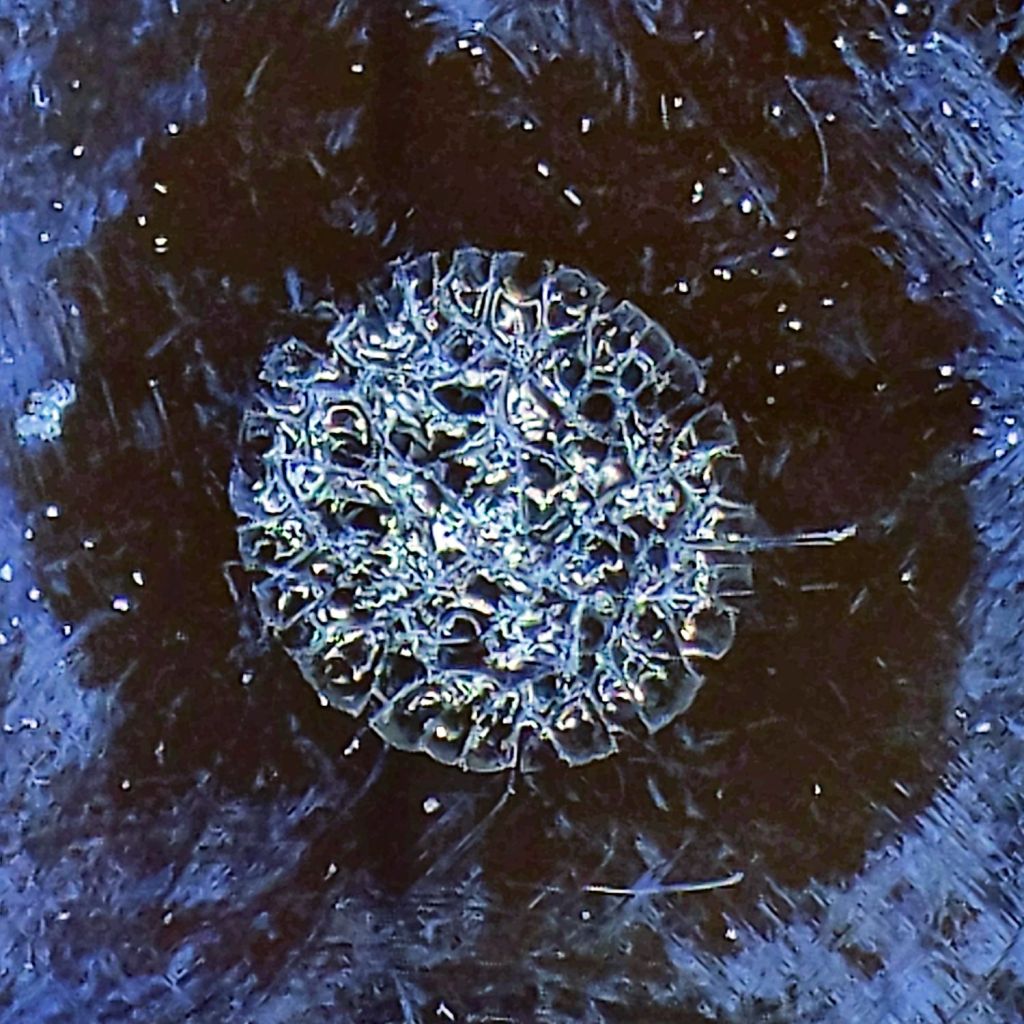

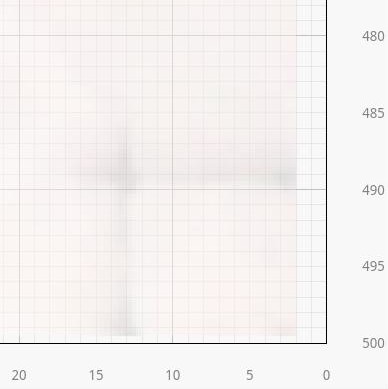

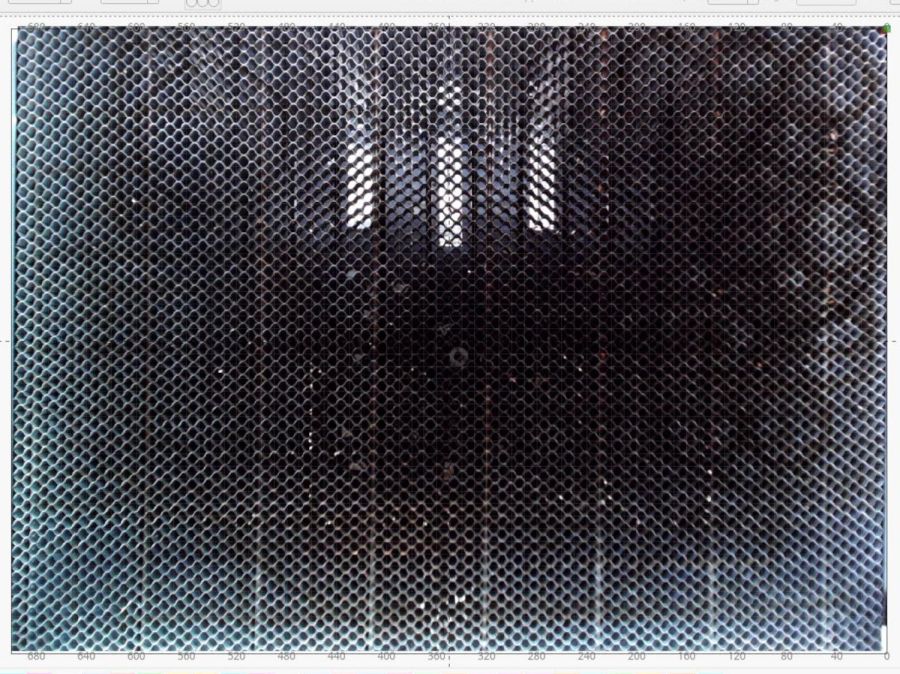

The beam produced the larger scar and also blasted off a ring of crud around the wound, as seen from the front surface:

The beam seems to have shattered a thin layer under the metallization, but didn’t do any deeper damage. The rear surface is undamaged and the paper didn’t have a scorch mark.

They’re not laser safety glasses, but at least they didn’t disintegrate.

Protip: do not lie on the laser platform and stare upward into the laser head, even while wearing fancy polarized mirrorshades.