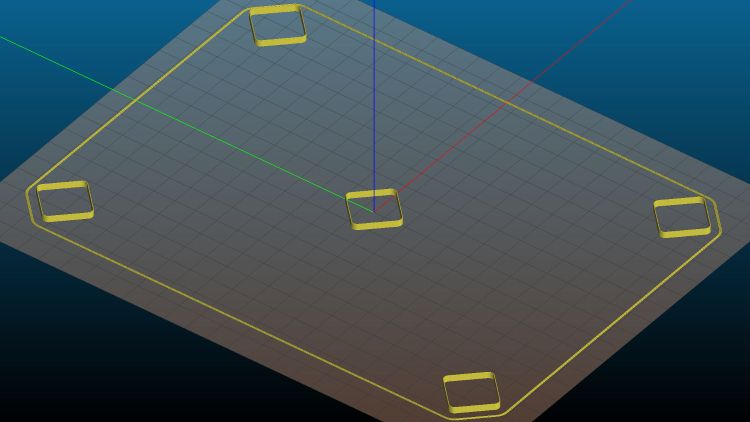

Although I was blithely unaware when I bought some useful-looking surplus, it turns out 1/16 inch armature wire works really well to seal our homebrew masks around our noses. Mary added a narrow passage along the top edge of her slightly reshaped Fu Mask pattern to retain the wire and I provided 4.5 inch lengths of straightened wire:

The wire comes off the roll in dead-soft condition, so I can straighten (and slightly harden) it by simply rolling each wire with eight fingertips across the battered cutting board. The slightly wavy wire shows its as-cut condition and the three straight ones are ready for their masks.

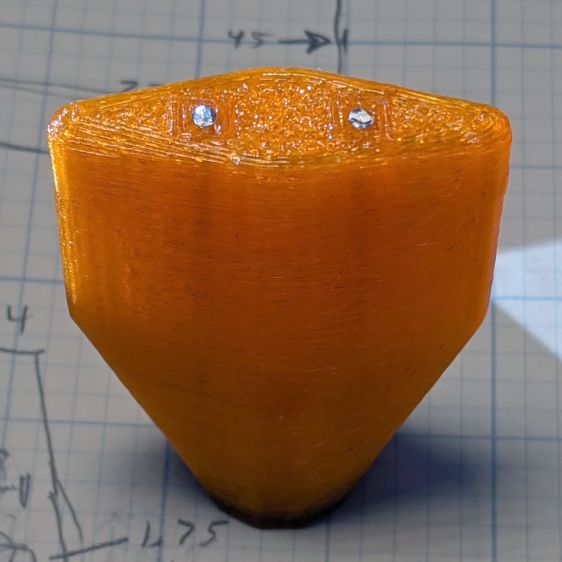

Although nearly pure aluminum wire doesn’t work-harden quickly, half a year of mask duty definitely takes its toll. This sample came from my biking mask after the edges wore out:

We initially thought using two wires would provide a better fit, but more metal just made adjusting the nose seal more difficult after each washing. The wire has work-hardened enough to make the sharper bends pretty much permanent; they can be further bent, but no longer roll out under finger pressure.

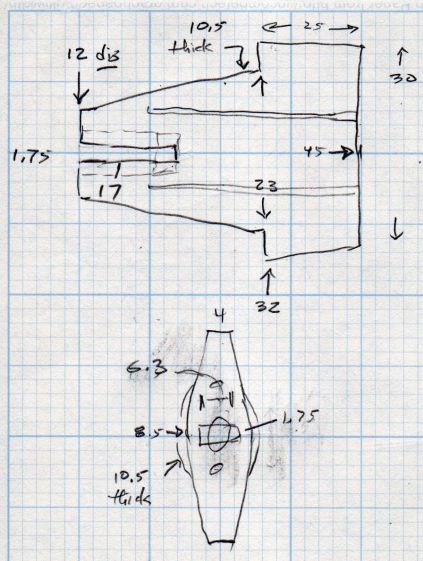

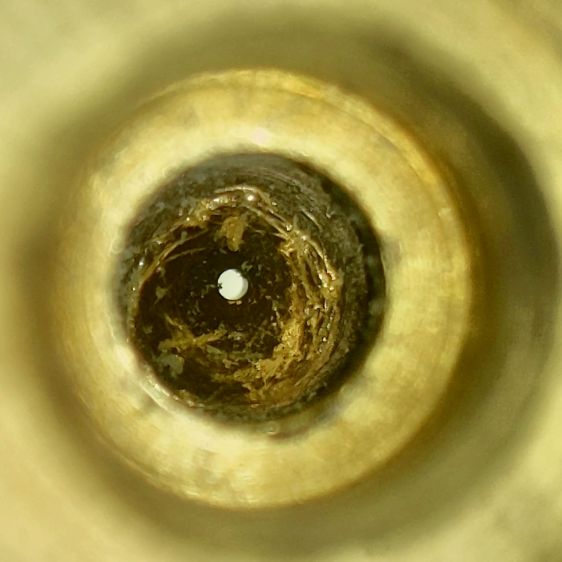

Although we’re not yet at the point where we must reuse wires, I took this as an opportunity to improve my annealing hand: heat the wire almost to its melting point, hold it there for a few seconds, then let it cool slowly. The usual technique involves covering the aluminum with something like hand soap or permanent marker ink, heat until the soap / marker burns away, then let it air-cool. Unlike steel, there’s no need for quenching or tempering.

Blue Sharpie worked surprisingly well with a propane torch:

As far as I can tell after a few attempts, the pigment vanishes just below the annealing temperature and requires another pass to reach the right temperature. Sweep the flame steadily, don’t pause, and don’t hold the wire over anything melt-able.

Those wires (I cut the doubled wire apart) aren’t quite as soft as the original stock, but they rolled straight and are certainly good enough for our simple needs; they’re back in the Basement Laboratory Warehouse for future (re)use.