In order to get the crash-test dummy stepper running on the X axis, I had to increase the FERROR and MIN_FERROR values by about two orders of magnitude from their defaults, which suggested I didn’t understand what I was doing and should run some numbers. I don’t profess to know how this works under the hood, though, but what follows seems to make sense.

Background reading:

Software step generation (which I’m not using) has an obvious limitation: the real-time software can produce at most one pulse per interrupt, so the maximum interrupt rate limits the maximum speed. The normal maximum rate is half a pulse per interrupt (the rising and falling edges occur on successive interrupts), but the software step generator can also produce a complete step pulse in a single interrupt; I don’t know the interaction between minimum step pulse width and interrupt period.

The maximum interrupt frequency / minimum interrupt period depends on the interrupt latency jitter, which seems to run around 5 to 10 μs for PC hardware that’s usable with software step generation. Assuming the pulse itself requires a few microseconds, then the minimum period seems to be around 20 to 25 μs, which limits the maximum step frequency to about 40 or 50 kHz. The Marlin firmware has an upper limit of 40000 step/s.

For comparison, a 50 μs base period works fine for the Sherline CNC mill, which tops out at 0.4 inch/s → 6400 step/s → 156 μs/step. That’s one reason converting a CNC mill to a 3D printer doesn’t work well; “normal” 3D printer speeds overtax leadscrews.

However, (I think) the fixed interrupt timing produces horrible period granularity: a 20 μs interrupt period = 50 kHz step frequency means that the next lower frequency with regular pulses is 25 kHz. Any speed requiring pulses between 25 kHz and 50 kHz will (I think) get irregular step timing that is, on the average, correct. That resembles Marlin’s multiple steps per interrupt bunching, without the fixed clumps.

To avoid all that, I’m using a Mesa 5i25 FPGA board that generates step timing in hardware based on a multi-megahertz clock. The specs don’t include a maximum step rate or granularity, but all indications are that it works wonderfully well; I plan to do some measurements to see what’s happening.

Assuming that the 5i25 can emit stepper pulses pretty much exactly when they’re supposed to happen, then the critical timing events depend on the servo loop period, for which everyone seems to use the default 1 ms. At each of those interrupts, the motion controller figures out what the stepper frequencies should be for the next period and twiddles the 5i25 to make them happen.

If, at the end of the next millisecond, the actual (calculated) and projected positions don’t match up, then the motion controller triggers a following error. This all happens in software, as there’s no actual position feedback from the motors.

Assuming that the required stepper pulse rate doesn’t exceed the maximum frequency, (I think) there’s only one point where a following error can happen: at the junction between constant-acceleration and constant-velocity motion. The worst case (seems to be) a G0 move that ramps upward from a dead stop to the maximum allowed speed with the maximum allowed acceleration for an axis. Recall that RepRap firmware seems to use the same code for G1 and limits the G0 speed to whatever the most recent F defined, so you tend to not find G0 commands in RepRap-family G-Code.

The Trajectory Control doc suggests that the planner uses half the maximum defined acceleration while blending path segments. I used the full acceleration, which seems reasonable for single, non-blended motion.

I don’t know if the motion planner forces the junction to fall exactly at an interrupt time, but if it doesn’t, then the axis could accelerate for nearly a whole period after it should start the constant-velocity part of the path. The incremental distance would be:

x = 1/2 a t2

Assuming 10 m/s acceleration, the excess distance would be 0.005 mm after 1 ms. The default FERROR value in PNCConf, which applies during rapid motion, turns out to be 0.0050 mm; I did see following errors as the motion begins, so I think that’s what triggers them.

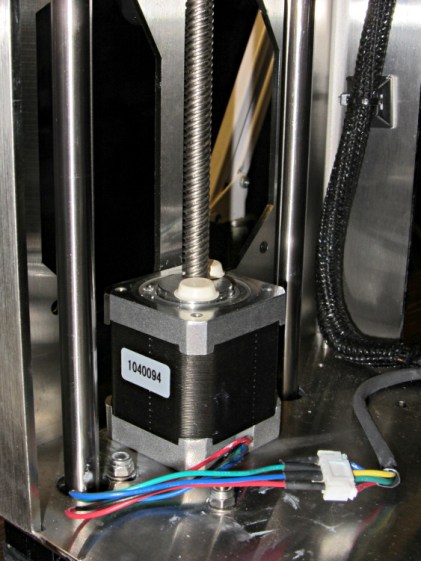

On the other end of the motion, where the motor slows at a constant acceleration to a dead stop, I think the final position may have a jitter of ±1 motor (micro)step, so the MIN_FERROR value must be at least twice as large as the minimum step size. The M2 runs at 88.9 step/mm (with 1/16 microstepping), so 1 step = 0.011 mm. The default MIN_FERROR in PNCConf is 0.0005 mm (half a micron!) and following errors happened quite predictably at the end of motion.

Sooooo, increasing MIN_FERROR by two orders of magnitude brought it to 0.0500 mm, a bit over the 0.022 = 2 * 0.011 required to cover the ±1 step endpoint error. Because I didn’t really understand what I was doing (and may not, even now), I had been changing both of the following error limits by factors of 10, and that last change turned out to be just enough.

While working all that out, I changed the M542 stepper brick DIP switches to use 1/20 microstepping, which increases the XY resolution to (36 mm/rev) / (4000 step/rev) = 0.009 mm/step → 111.1 step/mm. That doesn’t make any practical difference, but it pushes the XY step size below ten microns, which is certainly good for bragging rights. Yes, I know all about the lack of position accuracy from a microstepping motor, but work with me on this.

Based on those numbers, I picked:

FERROR = 0.050 mmMIN_FERROR = 0.020 mm

Given that 3D printing involves gooey molten plastic laid down in half-millimeter strips, micron-scale error limits really don’t make much practical difference, but at least now (I think) I understand a bit more about the error boundaries.

Also, these limits have nothing to do with the G61.x Exact Path / G64 Path Blending G-Code commands, which tell the motion planner how much slop to allow when computing the path. Given all that gooey plastic, running with something like G64 P0.1 Q0.1 might improve the overall speed quite a bit.