The values written to the I²C register controlling the Arducam Motorized Focus Camera lens position are strongly nonlinear with distance, so a simple linear increment / decrement isn’t particularly useful. If one had an equation for the focus value given the distance, one could step linearly by distance.

So, we begin.

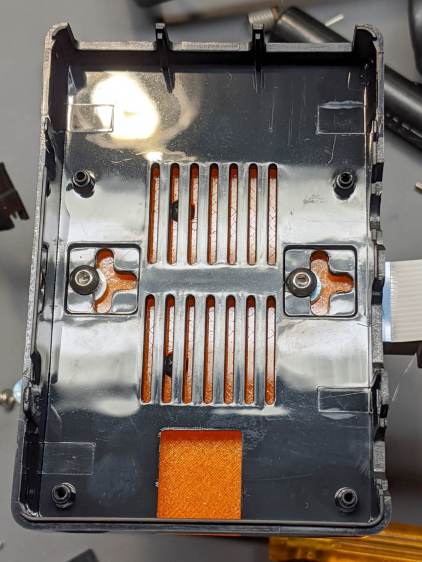

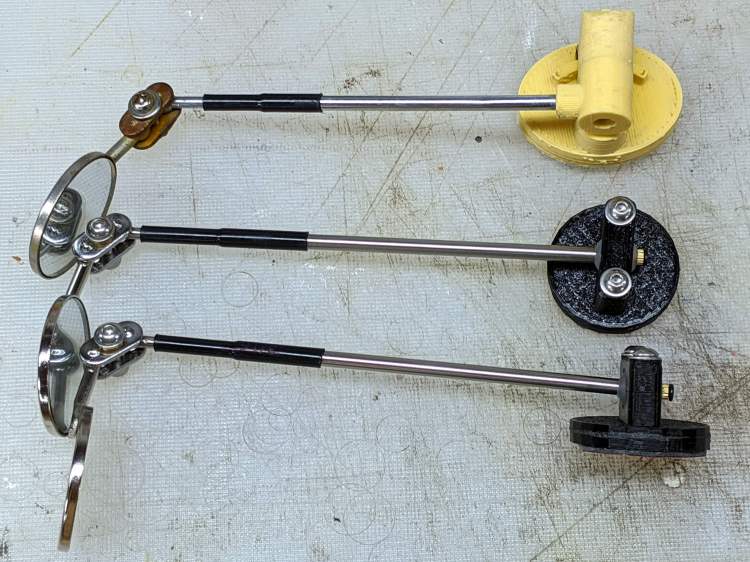

Set up a lens focus test range amid the benchtop clutter with found objects marking distances:

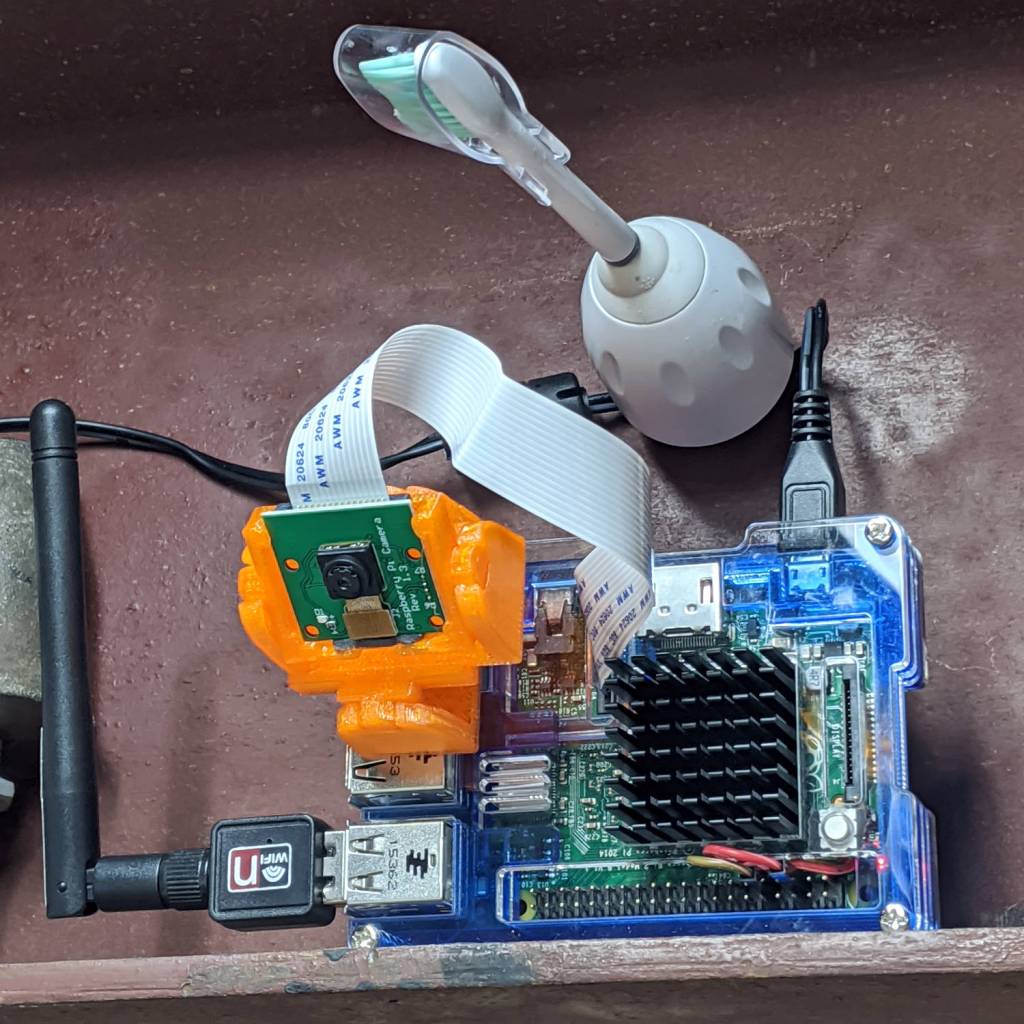

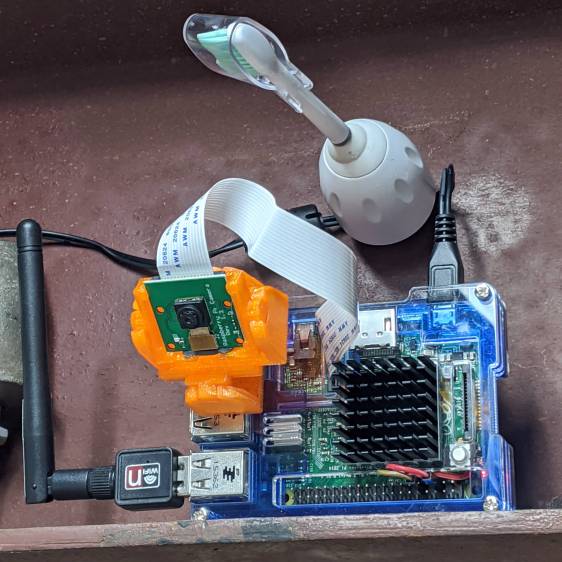

Fire up the video loopback arrangement to see through the camera:

The camera defaults to a focus at infinity (or, perhaps, a bit beyond), corresponding to 0 in its I²C DAC (or whatever). The blue-green scenery visible through the window over on the right is as crisp as it’ll get through a 5 MP camera, the HP spectrum analyzer is slightly defocused at 80 cm, and everything closer is fuzzy.

Experimentally, the low byte of the I²C word written to the DAC doesn’t change the focus much at all, so what you see below comes from writing a focus value to the high byte and zero to the low byte.

For example, to write 18 (decimal) to the camera:

i2cset -y 0 0x0c 18 0That’s I²C bus 0 (through the RPi camera ribbon cable), camera lens controller address 0x0c (you could use 12 decimal), focus value 18 * 256 + 0 = 0x12 + 0x00 = 4608 decimal.

Which yanks the focus inward to 30 cm, near the end of the ruler:

The window is now blurry, the analyzer becomes better focused, and the screws at the far end of the yellow ruler look good. Obviously, the depth of field spans quite a range at that distance, but iterating a few values at each distance gives a good idea of the center point.

A Bash one-liner steps the focus inward from infinity while you arrange those doodads on the ruler:

for i in {0..31} ; do let h=i*2 ; echo "high: " $h ; let rc=1 ; until (( rc < 1 )) ; do i2cset -y 0 0x0c $h 0 ; let rc=$? ; echo "rc: " $rc ; done ; sleep 1 ; doneWrite 33 to set the focus at 10 cm:

Then write 55 for 5 cm:

The tick marks show the depth of field might be 10 mm.

Although the camera doesn’t have a “thin lens” in the optical sense, for my simple purposes the ideal thin lens equation gives some idea of what’s happening. I think the DAC value moves the lens more-or-less linearly with respect to the sensor, so it should be more-or-less inversely related to the focus distance.

Take a few data points, reciprocate & scale, plot on a doodle pad:

Dang, I loves me some good straight-as-a-ruler plotting action!

The hook at the upper right covers the last few millimeters of lens travel where the object distance is comparable to the sensor distance, so I’ll give the curve a pass.

Feed the points into a calculator and curve-fit to get an equation you could publish:

DAC MSB = 10.8 + 218 / (distance in cm)

= 10.8 + 2180 / distance in mm)Given the rather casual test setup, the straight-line section definitely doesn’t support three significant figures for the slope and we could quibble about exactly where the focus origin sits with respect to the camera.

So this seems close enough:

DAC MSB = 11 + 2200 / (distance in mm)Anyhow, I can now tweak a “distance” value in a linear-ish manner (perhaps with a knob, but through evdev), run the equation, send the corresponding DAC value to the camera lens controller, and have the focus come out pretty close to where it should be.

Now, to renew my acquaintance with evdev …