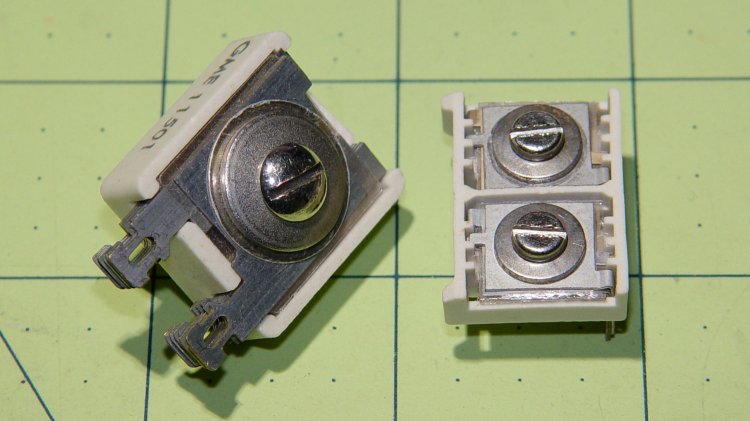

These items came near enough to produce an irresistible force:

How can you look at that layout and not jump to the obvious conclusion?

The front view suggests enough room for a stylin’ case:

You’d need only one cell for the camera; I happened to have two in my hand when the attractive force hit.

The camera is 24.5 ⌀ x 47 tall x 71.5 overall length (67.8 front-to-door-seating-plane).

The ATK 18650 cells are 19 ⌀ x 69 long, with the overlong length due to the protection PCB stuck on the + end of the cylinder. You can get shorter unprotected cells for a bit less, which makes sense if you’re, say, Telsa Motors and building them into massive batteries; we mere mortals need all the help we can get to prevent what’s euphemistically called “venting with flame“.

Although I like the idea of sliding the cell into a tubular housing with a removable end cap, it might make more sense to park the cell over the camera in a trough with leaf-spring contacts on each end and a lid that snaps over the top. That avoids threaded fittings, figuring out how to get an amp or so out of the removable end cap contact, and similar imponderables.

I think it’s possible to drill a hole through the bottom of the camera at the rear of the battery compartment to pass a cable from a fake internal cell to the external cell. Some delicate probing will be in order.

In round numbers, those 18650 cells allegedly have three times the actual capacity of the camera’s flat battery and cost about as much as the not-so-cheap knockoff camera cells I’ve been using.