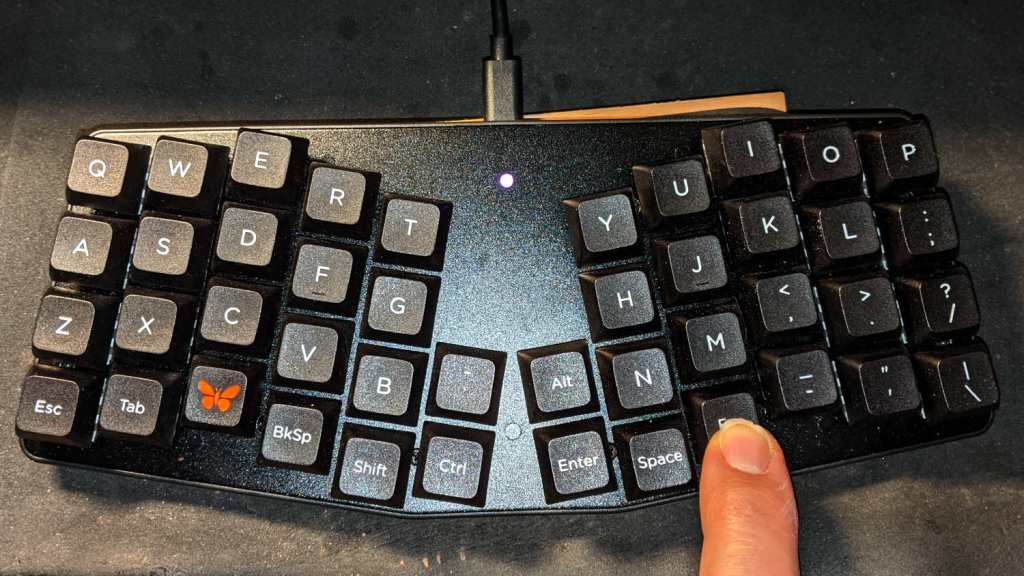

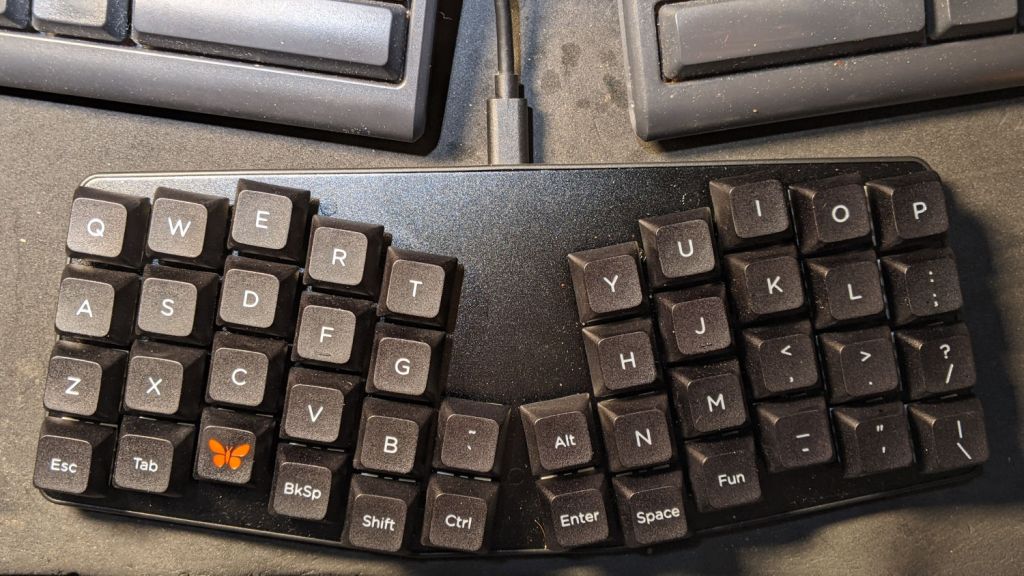

Having wired a WS2812 RGB LED into my KeyboardIO Atreus, lighting it up requires some QMK firmware configuration. It’s easiest to set up a “new” keymap based on the QMK Atreus files, as described in the QMK startup doc:

qmk new-keymap -kb keyboardio/atreus -km ednisleyObviously, you’ll pick a different keymap name than I did. All the files mentioned below will reside in the new subdirectory, which starts out with only a keymap.c file copied from the default layout.

The rules.mk file enables RGB Lighting, as well as Auto Shift and Tap Dance:

AUTO_SHIFT_ENABLE = yes # allow automagic shifting

TAP_DANCE_ENABLE = yes # allow multi-tap keys

RGBLIGHT_ENABLE = yes # addressable LEDs

If you had different hardware, you could specify the driver with a WS2812_DRIVER option.

QMK can also control single-color LEDs with PWM (a.k.a. backlighting), and per-key RGB LEDs (a.k.a. RGB Matrix). These functions, their configuration / controls / data, and their documentation overlap and intermingle to the extent that I spent most of my time figuring out what not to include.

Some configuration happens in the config.h file:

#define RGB_DI_PIN B2

#define RGBLED_NUM 1

// https://github.com/qmk/qmk_firmware/blob/master/docs/ws2812_driver.md

//#define WS2812_TRST_US 280

//#define WS2812_BYTE_ORDER WS2812_BYTE_ORDER_GRB

#define RGBLIGHT_LAYERS

#define RGBLIGHT_EFFECT_RGB_TEST

#define RGBLIGHT_LIMIT_VAL 63

#define NO_DEBUG

#define NO_PRINT

The first two lines describe a single WS2812 RGB LED wired to pin B2 (a.k.a. MOSI) of the Atmel 32U4 microcontroller. The default Reset duration and Byte Order values work for the LED I used

Protip: swapping the order from GRB to RGB is a quick way to discover if the firmware actually writes to the LED, even before you get anything else working: it’ll be red with the proper setting and green with the wrong one.

Dialing the maximum intensity down works well with a bright LED shining directly at your face from a foot away.

Turning on RGBLIGHT_LAYERS is what makes this whole thing happen. The RGBLIGHT_EFFECT_RGB_TEST option enables a simple test animation at the cost of a few hundred bytes of code space; remove that line after everything works.

The last two lines remove the debugging facilities; as always with microcontroller projects, there’s enough room for either your code or the debugger required to get it running, but not both.

With those files set up, the keymap.c file does the heavy lifting:

// Modified from the KeyboardIO layout

// Ed Nisley - KE4ZNU

#include QMK_KEYBOARD_H

enum layer_names {

_BASE,

_SHIFTS,

_FUNCS,

_NLAYERS

};

// Tap Dance

enum {

TD_SPC_ENT,

};

qk_tap_dance_action_t tap_dance_actions[] = {

[TD_SPC_ENT] = ACTION_TAP_DANCE_DOUBLE(KC_SPC, KC_ENT),

};

// Layer lighting

// Undefine this to enable simple test mode

// Also put #define RGBLIGHT_EFFECT_RGB_TEST in config.h

#define LED_LL

#ifdef LED_LL

const rgblight_segment_t PROGMEM ll_0[] = RGBLIGHT_LAYER_SEGMENTS( {0,1,HSV_WHITE} );

const rgblight_segment_t PROGMEM ll_1[] = RGBLIGHT_LAYER_SEGMENTS( {0,1,HSV_MAGENTA} );

const rgblight_segment_t PROGMEM ll_2[] = RGBLIGHT_LAYER_SEGMENTS( {0,1,HSV_CYAN} );

const rgblight_segment_t PROGMEM ll_3[] = RGBLIGHT_LAYER_SEGMENTS( {0,1,HSV_BLUE} );

const rgblight_segment_t PROGMEM ll_4[] = RGBLIGHT_LAYER_SEGMENTS( {0,1,HSV_GREEN} );

const rgblight_segment_t PROGMEM ll_5[] = RGBLIGHT_LAYER_SEGMENTS( {0,1,HSV_RED} );

const rgblight_segment_t PROGMEM ll_6[] = RGBLIGHT_LAYER_SEGMENTS( {0,1,HSV_YELLOW} );

const rgblight_segment_t* const PROGMEM ll_layers[] = RGBLIGHT_LAYERS_LIST(

ll_0,ll_1,ll_2,ll_3,ll_4,ll_5,ll_6

);

#endif

void keyboard_post_init_user(void) {

#ifdef LED_LL

rgblight_layers = ll_layers;

rgblight_set_layer_state(0, 1);

#else

rgblight_enable_noeeprom();

rgblight_mode_noeeprom(RGBLIGHT_MODE_RGB_TEST);

// rgblight_mode_noeeprom(RGBLIGHT_MODE_BREATHING + 3);

#endif

}

#ifdef LED_LL

layer_state_t layer_state_set_user(layer_state_t state) {

for (uint8_t i=0 ; i < _NLAYERS; i++)

rgblight_set_layer_state(i, layer_state_cmp(state, i));

return state;

}

#endif

// Key maps

const uint16_t PROGMEM keymaps[][MATRIX_ROWS][MATRIX_COLS] = {

[_BASE] = LAYOUT( // base layer for typing

KC_Q, KC_W, KC_E, KC_R, KC_T, KC_Y, KC_U, KC_I, KC_O, KC_P ,

KC_A, KC_S, KC_D, KC_F, KC_G, KC_H, KC_J, KC_K, KC_L, KC_SCLN ,

KC_Z, KC_X, KC_C, KC_V, KC_B, KC_GRV, KC_LALT, KC_N, KC_M, KC_COMM, KC_DOT, KC_SLSH ,

LT(_FUNCS,KC_ESC), KC_TAB, KC_LGUI, KC_BSPC, KC_LSFT, KC_LCTL, KC_ENT , TD(TD_SPC_ENT), MO(_SHIFTS), KC_MINS, KC_QUOT, KC_BSLS),

[_SHIFTS] = LAYOUT( // shifted chars and numpad

KC_EXLM, KC_AT, KC_UP, KC_DLR, KC_PERC, KC_PGUP, KC_7, KC_8, KC_9, KC_HOME,

KC_LPRN, KC_LEFT, KC_DOWN, KC_RGHT, KC_RPRN, KC_PGDN, KC_4, KC_5, KC_6, KC_END,

KC_LBRC, KC_RBRC, KC_HASH, KC_LCBR, KC_RCBR, KC_CIRC, KC_AMPR,KC_ASTR, KC_1, KC_2, KC_3, KC_PLUS,

KC_NO , KC_INS, KC_LGUI, KC_DEL , KC_BSPC, KC_LCTL, KC_LALT,KC_SPC, KC_TRNS, KC_DOT, KC_0, KC_EQL ),

[_FUNCS] = LAYOUT( // function keys

KC_INS, KC_HOME, KC_UP, KC_END, KC_PGUP, KC_UP, KC_F7, KC_F8, KC_F9, KC_F10 ,

KC_DEL, KC_LEFT, KC_DOWN, KC_RGHT, KC_PGDN, KC_DOWN, KC_F4, KC_F5, KC_F6, KC_F11 ,

KC_NO, KC_VOLU, KC_NO, KC_NO, RESET, _______, _______, KC_NO, KC_F1, KC_F2, KC_F3, KC_F12 ,

KC_NO, KC_VOLD, KC_LGUI, KC_LSFT, KC_BSPC, KC_LCTL, KC_LALT, KC_SPC, TO(_BASE), KC_PSCR, KC_SLCK, KC_PAUS )

};

Undefine LED_LL to enable the test mode, compile, flash, and the LED should cycle red / green / blue forever; you also need the RGB_TEST option in the config.h file.

Define LED_LL and layer lighting should then Just Work™, with the LED glowing:

- White for the basic layer with all the letters

- Magenta with the Fun key pressed

- Cyan with the Esc key pressed

The key map code defines colors for layers that don’t yet exist, but it should get you started.

For convenience, I wadded all three QMK files into a GitHub Gist.

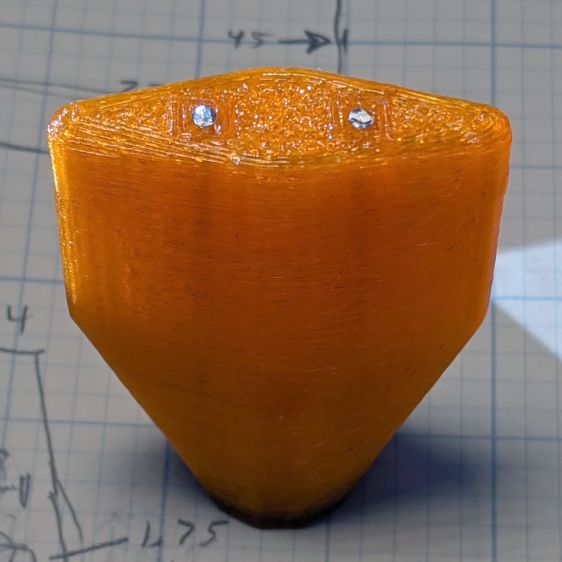

The LED is kinda subtle:

As you might expect, figuring all that out took much longer than for you to read about it, but now I have a chance of remembering what I did.