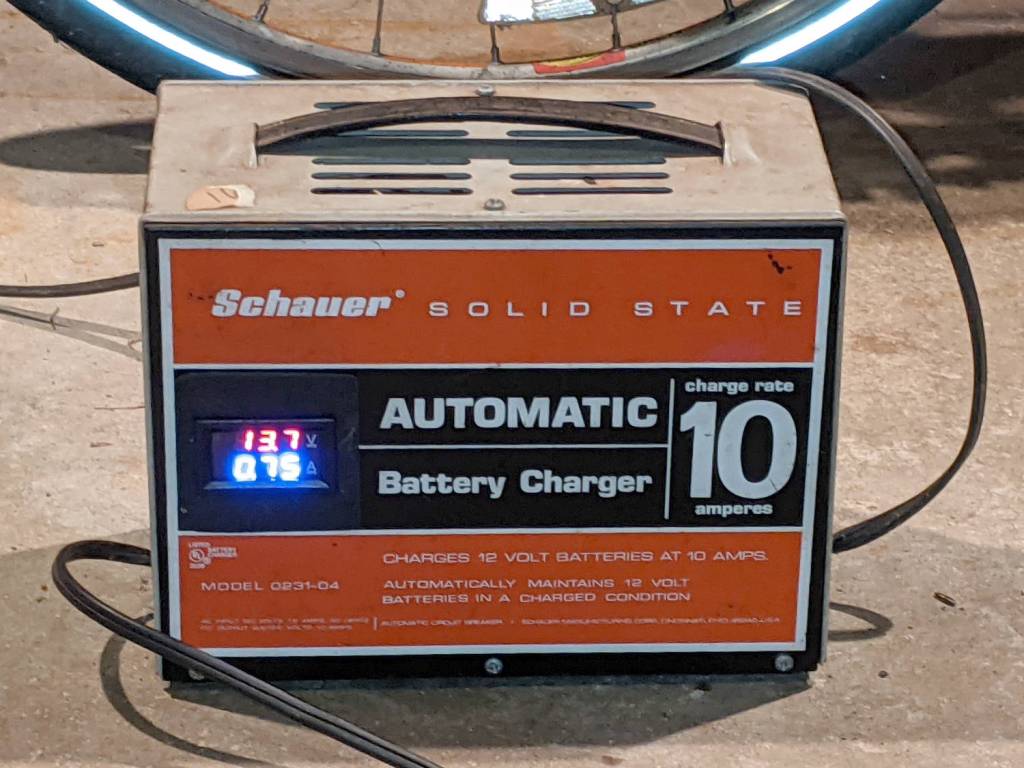

The Forester’s battery has been on life support from an ancient Schauer “Solid State” charger (which may have Come With The House™) for the last year:

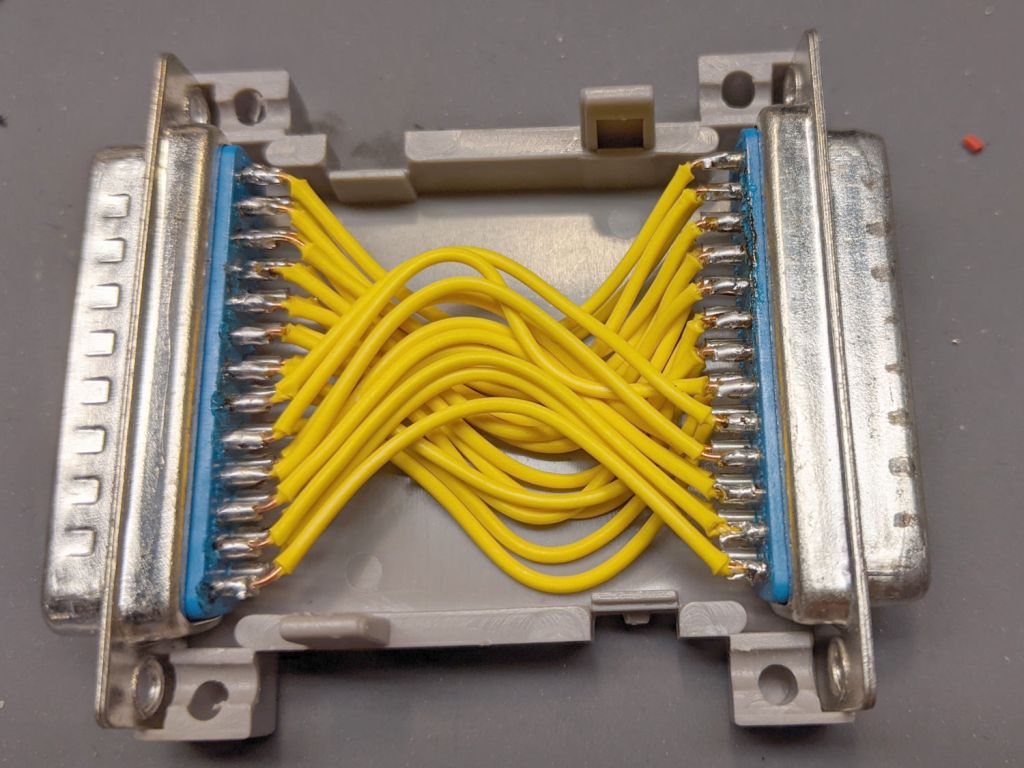

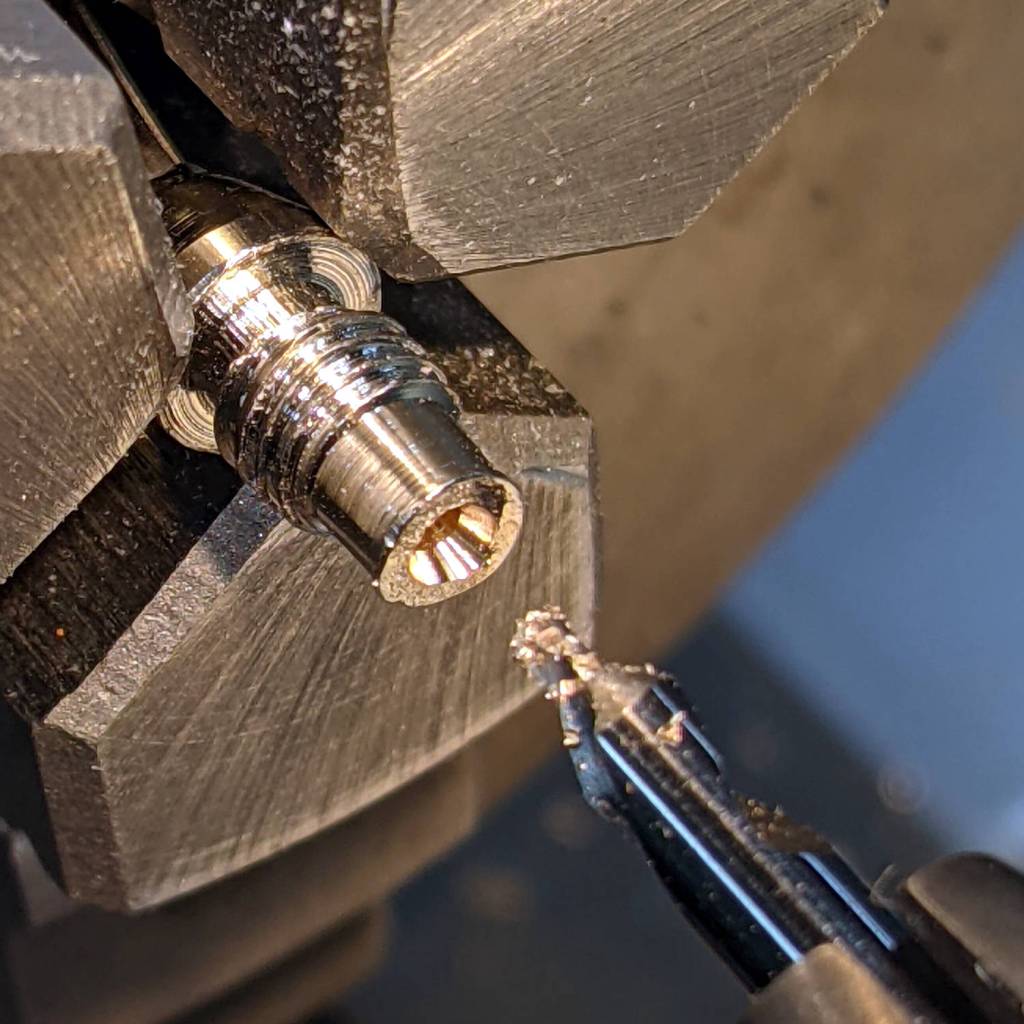

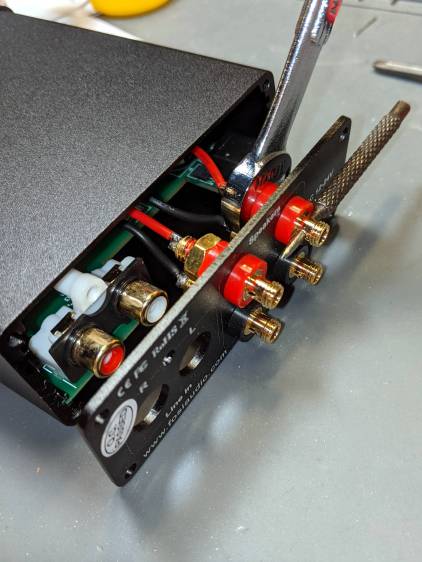

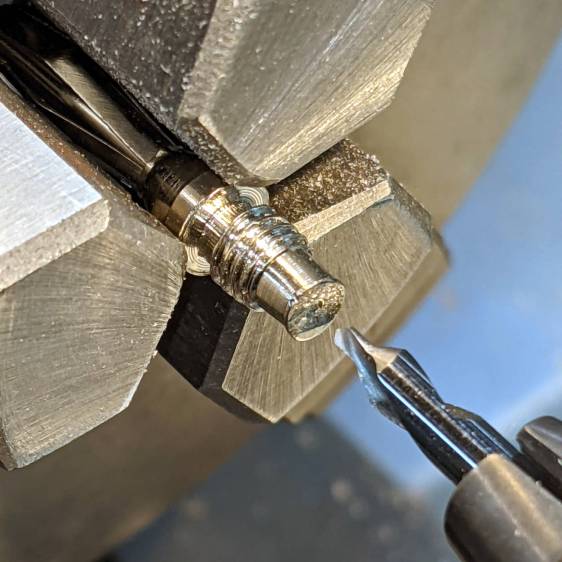

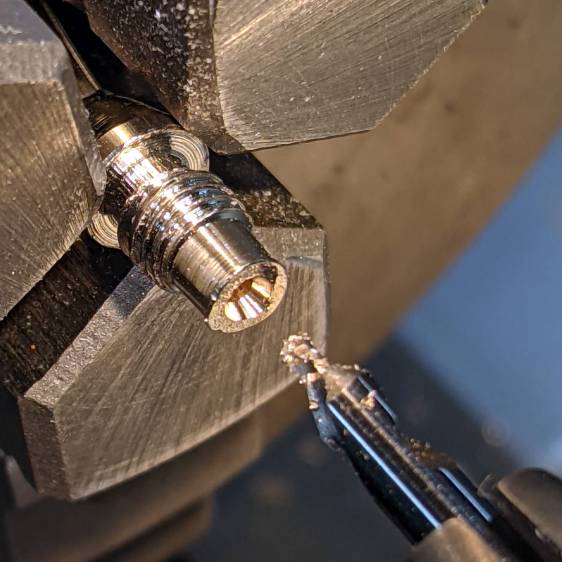

A remote Squidwrench session provided an opportunity to replace its OEM ammeter with a cheap volt-amp meter:

The charger is “solid state” because it contains silicon electronics:

That’s an SCR implanted in the aluminum heatsink. The other side has a Motorola 18356 house number, a date code that might be 523, and the word MEXICO. The company now known as NXP says Motorola opened its Guadalajara plant in 1969, so they could have built the SCR in either 1973 or 1975; it’s not clear who manufactures what these days.

The black tubing contains at least one part with enough value to justify the (presumably) Kovar lead; nowadays, it would be a “gold tone” finish. It’s probably a Zener diode setting the trickle-charging voltage, joined to the resistor lead in the crimped block. I don’t know if the glass diode is soldered to the Zener, but I’m reasonably sure if the third lead came from a transistor tucked inside the sleeve, we’d read about it on the charger’s front cover.

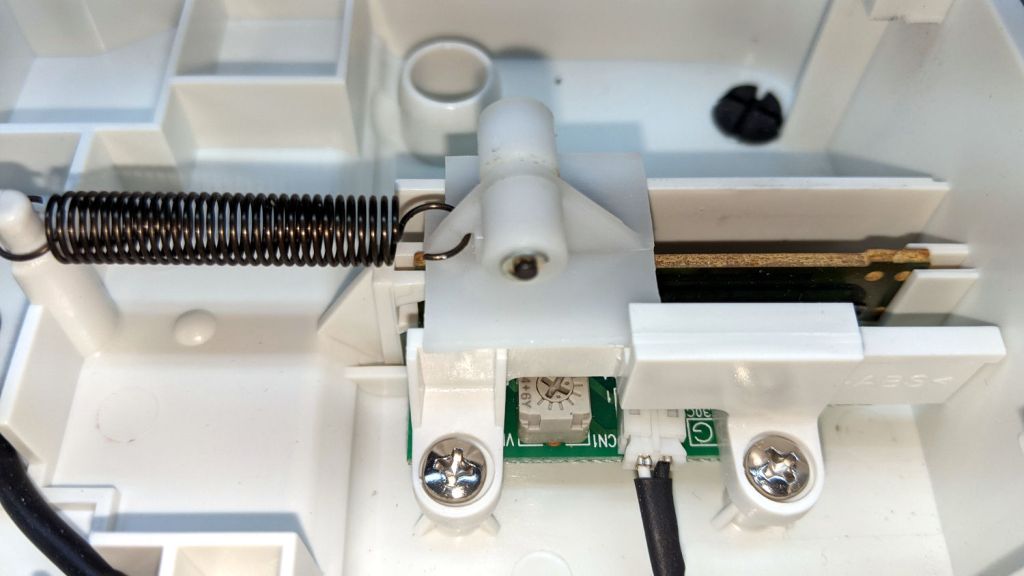

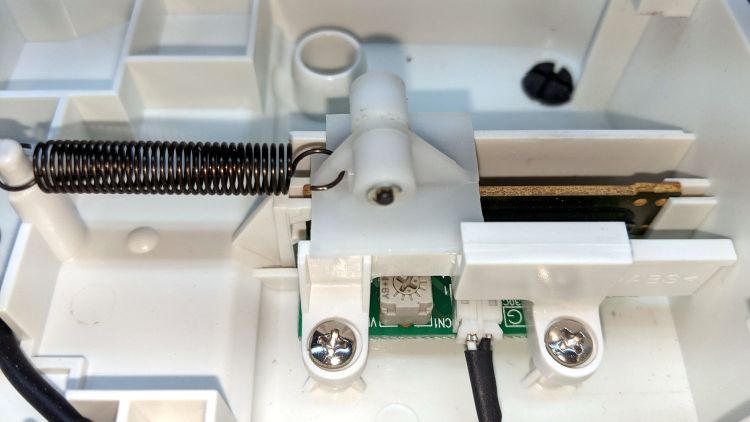

In an ideal world, a digital meter would fit into a matching rectangular hole in the front panel, but that’s not the world we live in. After wrestling my gotta-make-a-solid-model jones to the floor, I got primal on a random slab of soft-ish plastic sheet:

There’s nothing like some bandsaw / belt sander / nibbler action to jam a square peg into a round hole:

It’s actually a firm press fit; whenever something like that happens, you know the project will end well.

Hot melt glue FTW:

The new meter’s (heavy) red-black leads go to the same terminals as the old meter’s wires, paying attention to the polarity. I splurged with insulated QD terminals on the old wires where a joint was needed.

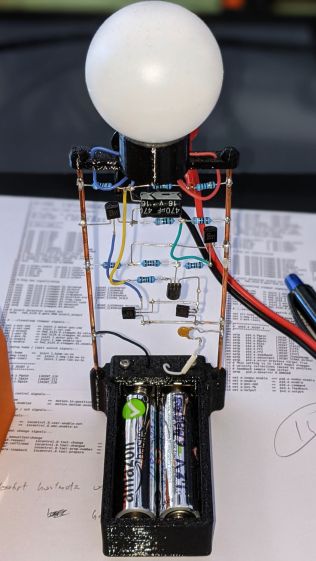

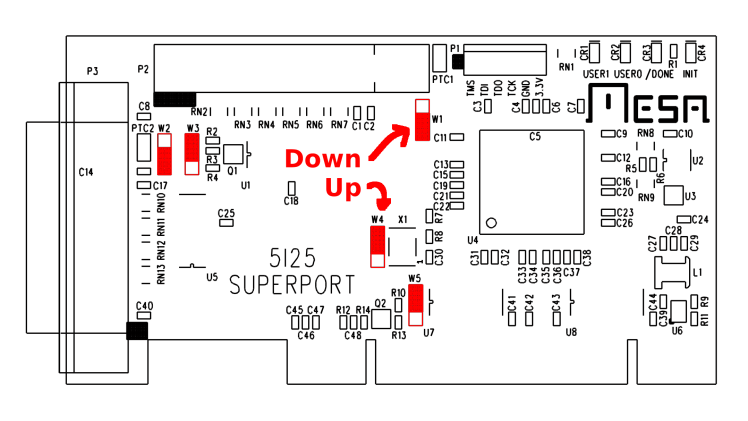

The meter’s thin red lead expects to see a power supply under 50 V with no particular regulation requirements, so I used the same flying-component design as the rest of the charger:

The meter draws basically no current, at least on the scale of an automotive battery charger, so the 220 µf cap holds pretty nearly the peak 18 V half-wave rectified from the center tap by a 1N5819 Schottky diode.

Those two squares riveted to the back panel are genuine selenium rectifiers, from back in the day when silicon power diodes weren’t cheap and readily available. They also limit the charger’s peak current and have yet to emit their incredibly foul stench upon failure; you always know exactly what died when that happens.

Selenium rectifiers were pretty much obsolete by the early 1970s, agreeing with a 1973 date code. Schauer might have been working through their stockpile of obsolete rectifiers, which would have been sunk-cost-cheap compared to silicon diodes.

The meter’s thin black lead goes to the power supply common point, which turns out to be where those rectifiers meet. The larger black wire goes off to the meter’s fat black lead on the other side of the aluminum heatsink, joining it in a new insulated QD terminal.

The meter’s thin yellow wire is its voltage sense input, which gets soldered directly to the hot lead of the SCR.

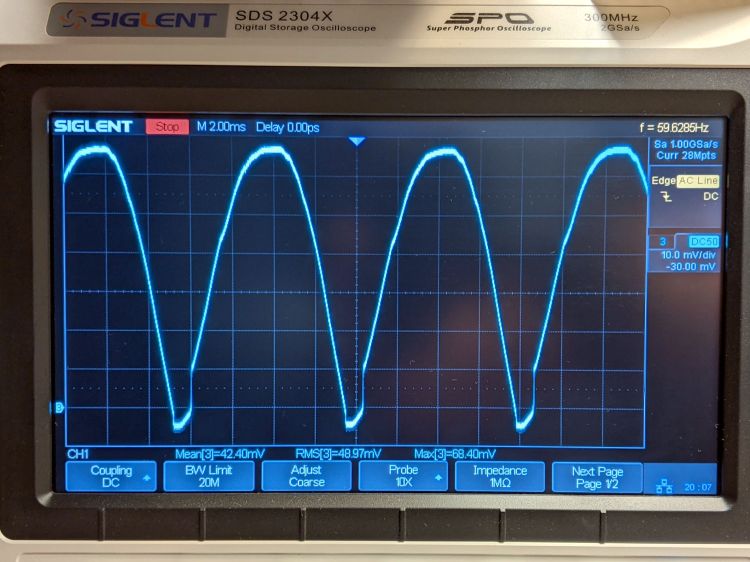

The meter indicates DC voltages and currents, which definitely isn’t the situation in the 100 Ω power resistor shown in the second picture.

The voltage:

And the current at 20 mA/div, showing why silicon replaced selenium:

Yes, the current does go negative while the rectifiers figure out what to do next.

The charger seems a little happier out in the garage:

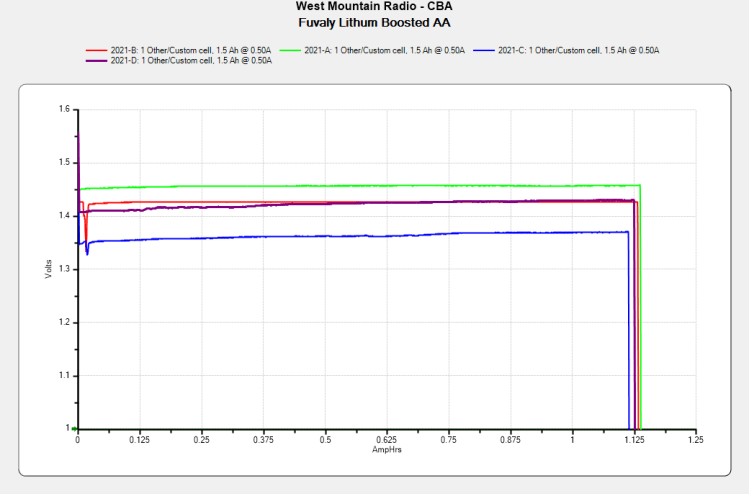

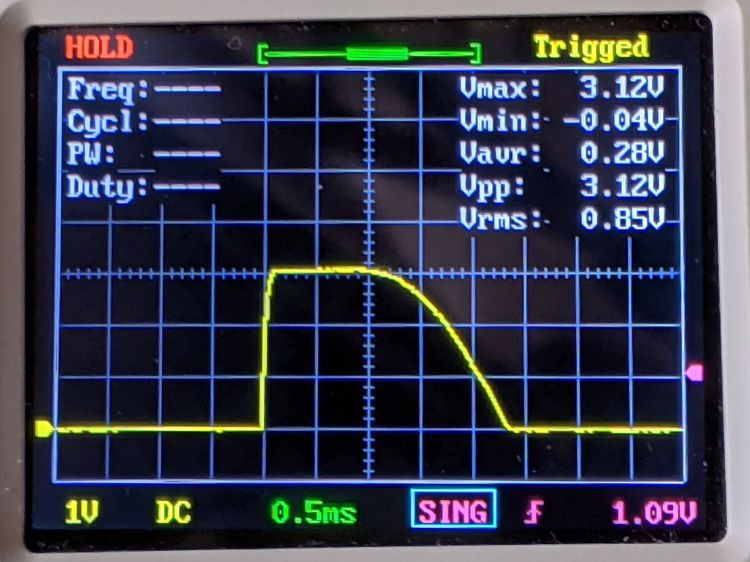

The battery holds the voltage steady at 13.7 V, with the charger producing 85 mV blips every second or so:

Those blips correspond to 3 A pulses rammed into the battery:

They’re measured across a 1 Ω series resistor that’s surely limiting the maximum current: 18 V from the transformer minus 13.7 V on the battery minus other IR losses doesn’t leave room for anything more than 3 V across the resistor. I wasn’t going to haul the Tek current probes out to the garage just for the occasion.

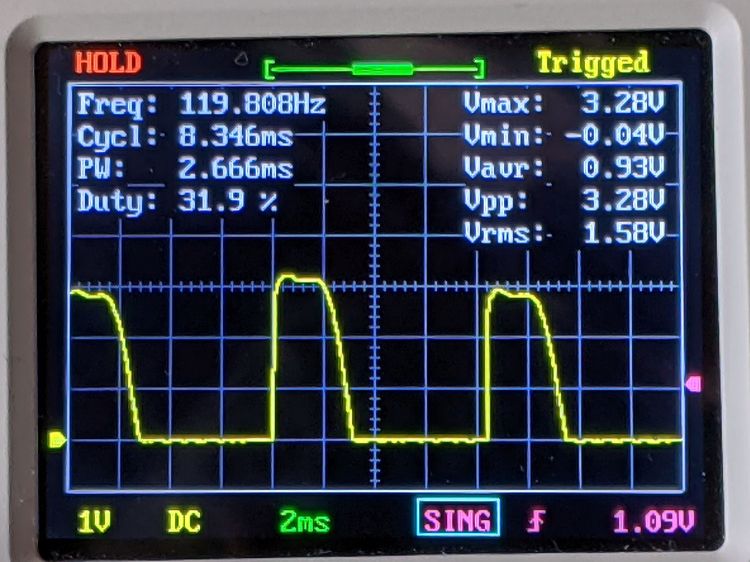

Opening the Forester’s door to turn on all its LED interior lights bumps the meter to about 1 A, although the truth is more complicated:

The average current is, indeed, just under 1 A, but in this situation the meter’s cool blue number seems more like a comfort indicator than anything particularly reliable.

All I really wanted from the meter was an indication that the trickle charger was trickling, so I disconnected Tiny Scope, declared victory, and closed the garage door.