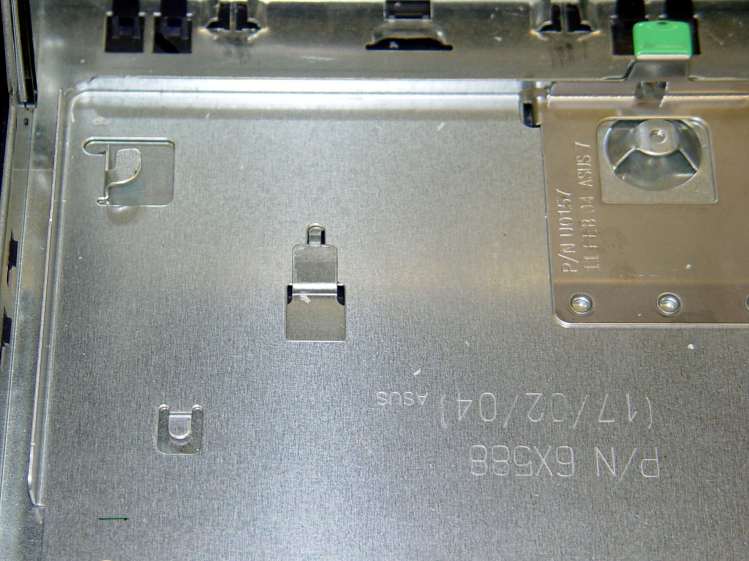

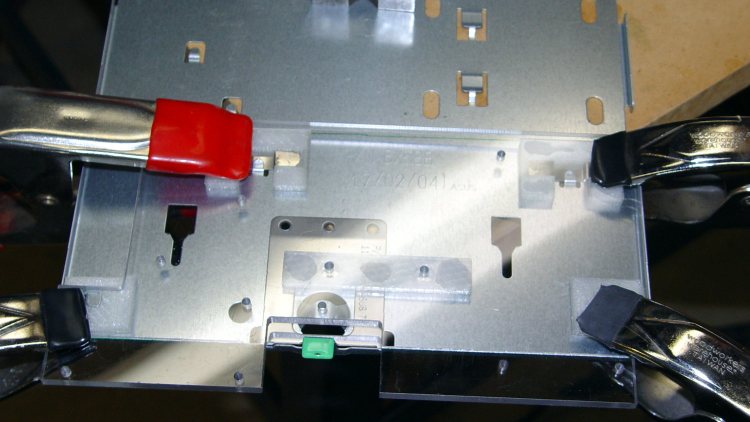

The Dell GX270 system board mounts on a tray, latching into small tabs, with a single screw locking it in place. The tray then slides into the metal EMI shield / case, latching onto more tabs, with a spring-loaded pair of tabs snapping into a slot under the green latch:

All that is well and good for a mass-production PC system board, but poses a problem for mounting anything else: there’s no room for screw heads below the tray, adhesives really don’t bond to slightly flexible aluminum sheets, and I definitely can’t do large-scale precision metal bending.

So a cheat seems in order. The general idea is to support a 6 mm polycarbonate sheet on clips that slide under the small tabs along the front, support the sheet on the rear tabs, and secure it with the screw. That’s thick enough to allow tapping holes for mounting screws, so everything else can mount to the sheet.

The sheet fits around the power supply on the right, protrudes over the rear of the tray to the back of the case (with a recess around the green latch), and clears the hinge assembly on the left. There are no dimensions, as it’s all done by eye with the Joggy Thing.

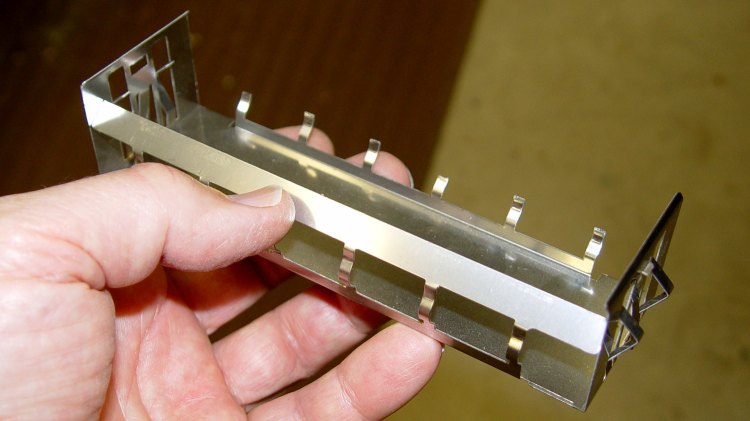

A drive bay EMI plug from a long-discarded PC provided some nice springy steel strips that slide neatly under those tray tabs:

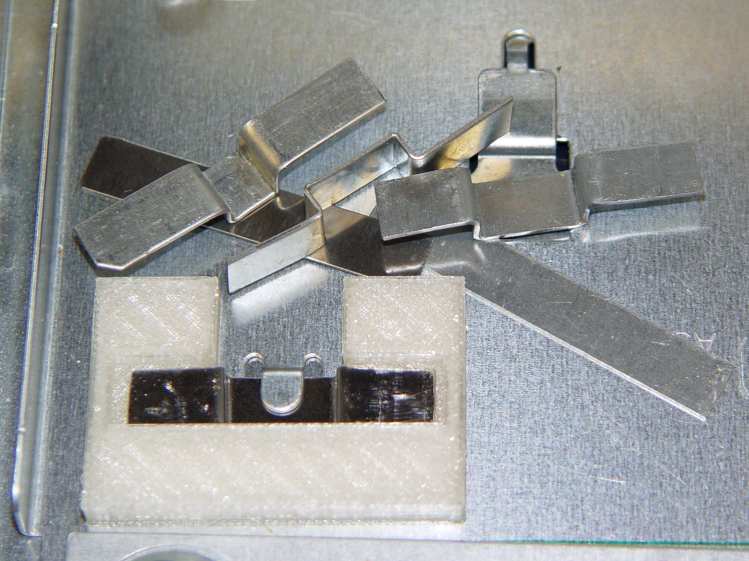

That actually took a bit of trial-and-error:

My first attempts used slightly thicker steel that didn’t fit nearly as well, plus I wasn’t quite sure how wide they should be.

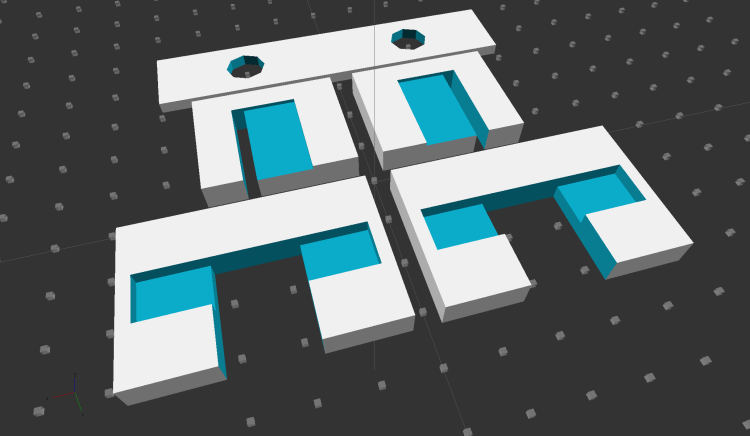

As with nearly all plastic doodads around here, the white plastic mounting clips / brackets come from the M2:

The two brackets in the middle of the solid model slide around the tabs at the rear corners of the tray and capture the bent-over top section below the polycarbonate sheet.

The strip in the rear goes around the screws holding the heatsink to the sheet; more on that later.

The PLA brackets get themselves glued to the sheet with IPS #4 solvent adhesive, a hellish mixture of chlorinated hydrocarbons that attacks most plastics with gleeful enthusiasm. I positioned the brackets on the tray, slobbered adhesive on their tops, slapped the polycarbonate sheet in place, and applied clamps:

The final bonds weren’t as uniform as I’d like, but they seem rugged enough. The lip along the rear of the tray was slightly higher on the left edge, which may have interfered with the clamping pressure; it’s obviously not a controlled dimension.

The tapped holes in the sheet accommodate screws for various bits & pieces.

All in all, that worked out pretty well…

The OpenSCAD source code:

// AC Interface sheet mounting brackets

// Ed Nisley - KE4ZNU - August 2014

Layout = "Build"; // FrontClip RearClip HeatSink Build

Gap = 5.0; // between Build objects

//- Extrusion parameters must match reality!

ThreadThick = 0.20;

ThreadWidth = 0.40;

HoleWindage = 0.2; // extra clearance

Protrusion = 0.1; // make holes end cleanly

AlignPinOD = 1.70; // assembly alignment pins: filament dia

function IntegerMultiple(Size,Unit) = Unit * ceil(Size / Unit);

//----------------------

// Dimensions

FC_Block = [45.0,30.0,IntegerMultiple(5.6,ThreadThick)];

FC_Retainer = [15.5,9.0,3.0,15.0]; // central section: L,W,H, inset from front

RC_Block = [30.0,25.0,IntegerMultiple(5.6,ThreadThick)];

RC_RecessOffset = [9.0,5.0,IntegerMultiple(4.8,ThreadThick)]; // X,Y,thickness

RC_SlotWidth = 2.5;

HS_Insulation = [80.0,16.0,2.5];

HS_Hole = [8.0,40.0]; // screw clearance dia,on-center

//----------------------

// Useful routines

module PolyCyl(Dia,Height,ForceSides=0) { // based on nophead's polyholes

Sides = (ForceSides != 0) ? ForceSides : (ceil(Dia) + 2);

FixDia = Dia / cos(180/Sides);

cylinder(r=(FixDia + HoleWindage)/2,

h=Height,

$fn=Sides);

}

module ShowPegGrid(Space = 10.0,Size = 1.0) {

RangeX = floor(100 / Space);

RangeY = floor(125 / Space);

for (x=[-RangeX:RangeX])

for (y=[-RangeY:RangeY])

translate([x*Space,y*Space,Size/2])

%cube(Size,center=true);

}

//----------------------

// Front clips

module FrontClip() {

difference() {

translate([0,0,FC_Block[2]/2])

cube(FC_Block,center=true);

translate([0,(FC_Retainer[3] - FC_Block[1]/2),(FC_Retainer[2] + FC_Block[2]/2)])

cube([(FC_Block[0] - 12*ThreadWidth),FC_Retainer[1],FC_Block[2]],center=true);

translate([0,FC_Retainer[3] - FC_Retainer[1]/2,FC_Block[2]/2])

cube([FC_Retainer[0],FC_Block[1],2*FC_Block[2]],center=true);

}

}

//----------------------

// Rear clips

module RearClip(Hand="Left") {

HandSign = (Hand == "Left") ? -1 : 1;

difference() {

translate([0,0,RC_Block[2]/2])

cube(RC_Block,center=true);

translate([0,RC_RecessOffset[1],RC_RecessOffset[2] + RC_Block[2]/2])

cube([RC_Block[0] - 2*RC_RecessOffset[0],

RC_Block[1],

RC_Block[2]],center=true);

translate([HandSign*(RC_Block[0]/2 - RC_RecessOffset[0]),

RC_RecessOffset[1],

0])

cube([RC_SlotWidth,RC_Block[1],3*RC_Block[2]],center=true);

}

}

//----------------------

// Heatsink bumper

module HeatSink() {

difference() {

translate([0,0,HS_Insulation[2]/2])

cube(HS_Insulation,center=true);

for (x=[-1,1])

translate([x*HS_Hole[1]/2,0,-HS_Insulation[2]])

PolyCyl(HS_Hole[0],3*HS_Insulation[2],8);

}

}

ShowPegGrid();

if (Layout == "FrontClip") {

FrontClip();

}

if (Layout == "RearClip") {

RearClip("Left");

}

if (Layout == "HeatSink") {

HeatSink();

}

if (Layout == "Build") {

for (x=[-1,1]) {

translate([x*(Gap + FC_Block[0])/2,(Gap + FC_Block[1])/2,0])

FrontClip();

translate([x*(Gap + RC_Block[0])/2,-(Gap + RC_Block[1])/2,0])

RearClip((x == -1) ? "Left" : "Right");

}

translate([0,-(RC_Block[1] + HS_Insulation[1]/2 + 3*Gap/2),0])

HeatSink();

}