Dell built the GX270 I’m repurposing back in 2004, early on in the capacitor plague years, but only one of the system board caps showed signs of leakage:

While I was harvesting some of the connectors, it occurred to me that those powdered iron inductors might make good current sensors, as they’re already wound with heavy gauge copper wires.

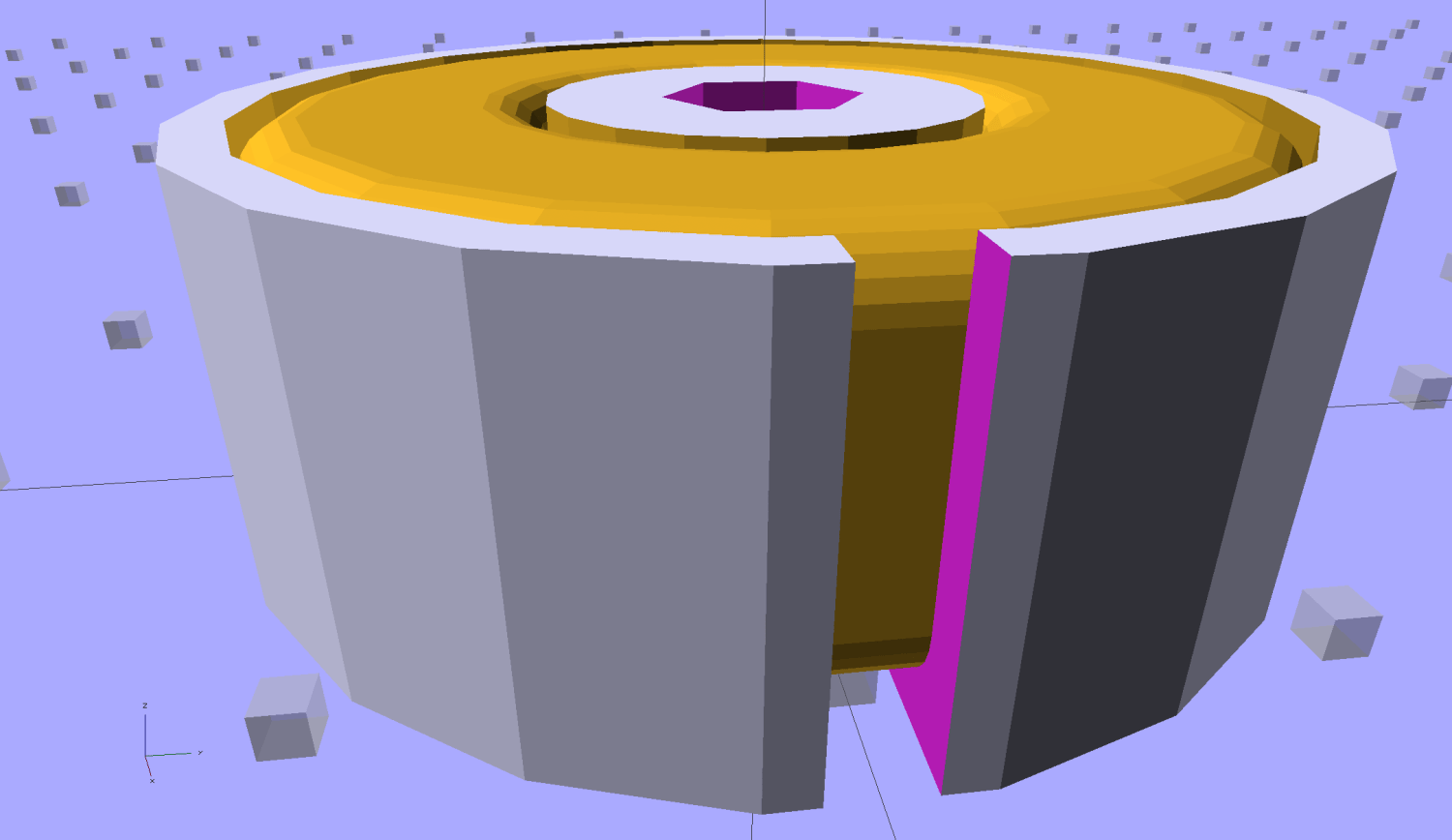

I picked an inductor with enough turns and, although slitting didn’t pose much of a problem, the saw did make a mess of the turns adjacent to the cut:

Iron powder has more magnetic remnance than ferrite, to the extent that iron swarf clogged the gap. After the first pass, I ran the slit toroid through the degausser to shake it clean and see what damage had been done. It looked OK, so I realigned it on the saw blade and continued the mission, with all the dust vanishing into the vacuum cleaner’s snout.

Removing the damaged sections left 22 turns. For comparison, I converted the 56 turn ferrite toroid into a 25 turn model by paralleling two 25 turn sections:

The enamel wire on the iron toroid measures 40 mil diameter, close enough to 18 AWG.

Paralleling two 24 AWG windings on the ferrite toroid produces twice the copper area of a single winding, so the resistance is the same as a single 21 AWG winding (3 AWG steps = factor of two area change). That’s three steps smaller than the 18 AWG on the iron toroid, so the resistance is a factor of two larger than the heavier wire.

The paralleled winding has the advantage of reducing the power dissipation required to produce the same magnetic flux density, without the difficulty of winding heavier wire. That may not actually matter, given the relatively low currents required by the motor in normal operation.

Wedging a Hall sensor into the gaps and stepping the current produced two useful graphs:

The iron toroid has lower permittivity (less flux density for a given magnetizing force), which means the full-scale range exceeds 3 A and the useful range up to 1 A covers only 300 mV.

The last point on the ferrite curve shows the Hall sensor output saturating just over 4 V, with 1.5 V of range.

The slope, in mV/A

- Powdered iron: 340

- Ferrite: 540

Boosting the slope of the powdered iron by 25/22 gives 386 mV/A, so the iron permeability really is 70% of the ferrite. That’s modulo the gap size, of course, which surely differs by enough to throw out all the significant digits.

Obviously, an op amp circuit to remove the offset and rescale the output to 0-5 V will be in order.

The previous graph for the ferrite toroid with the complete 56 turn winding shows, as expected, about twice the output of this 25 turn version:

The linear part of that line is 1375 mV/A, although I can’t vouch that the data came from the same Hall effect sensor. Scaling it by 25/56 gives 613 mV/A, suggesting it’s not the same sensor.

Having developed an emotional attachment to the ferrite toroid, I’ll use it in the first pass of the current feedback circuit. If the motor need a bit less sensitivity or lower resistance, the powdered iron toroid looks like a winner.

Memo to self: Always degauss iron toroids before slitting!