Stipulated: A chuck rotary doesn’t need a home switch.

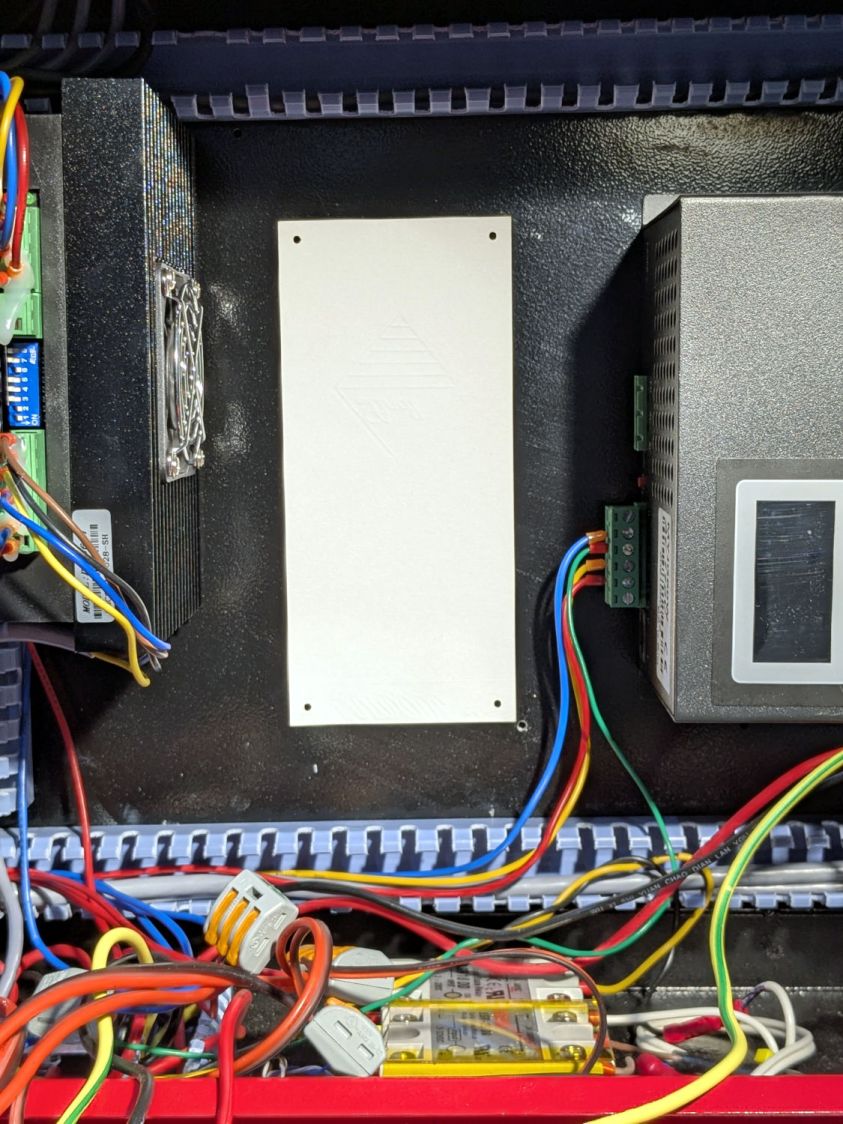

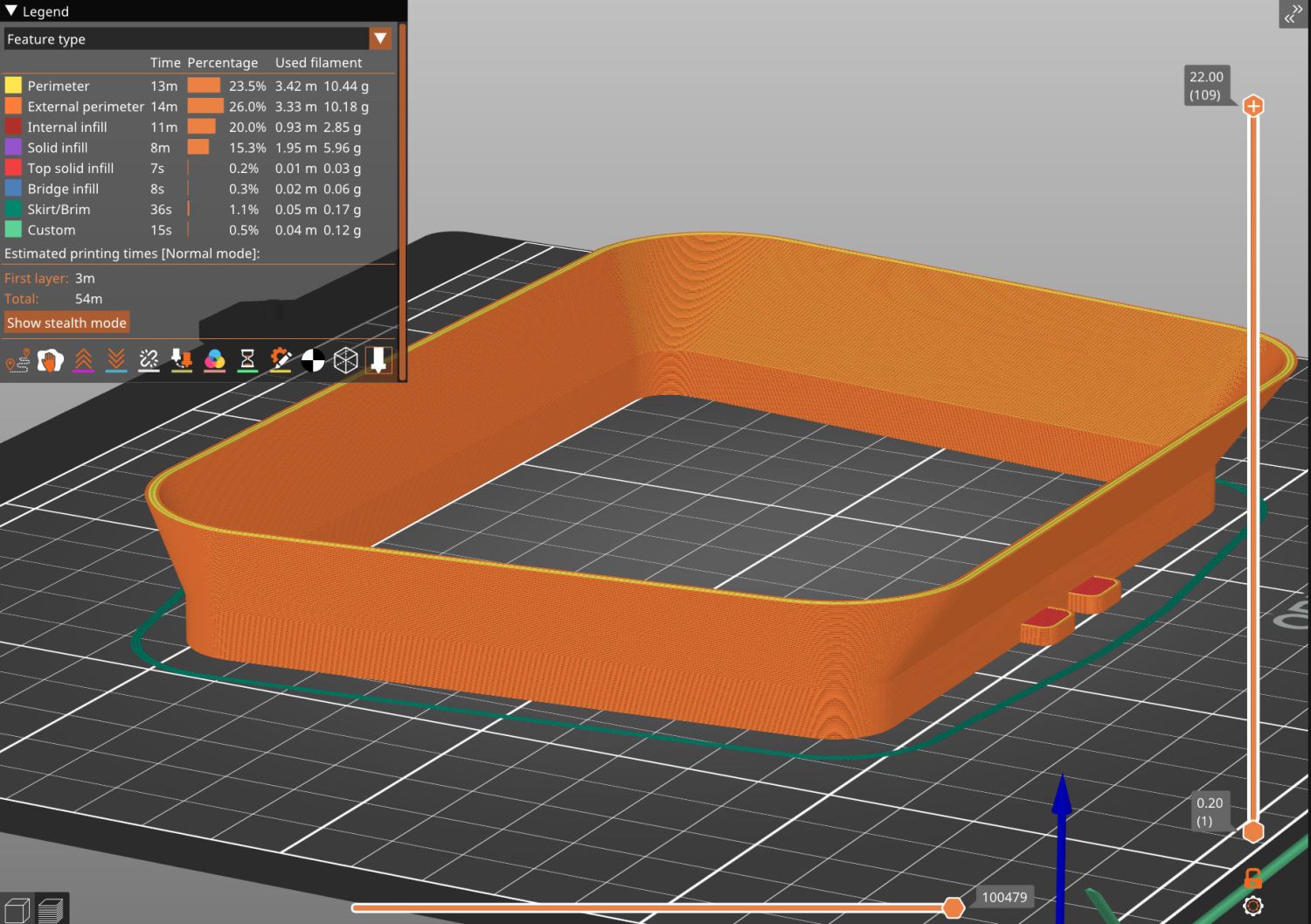

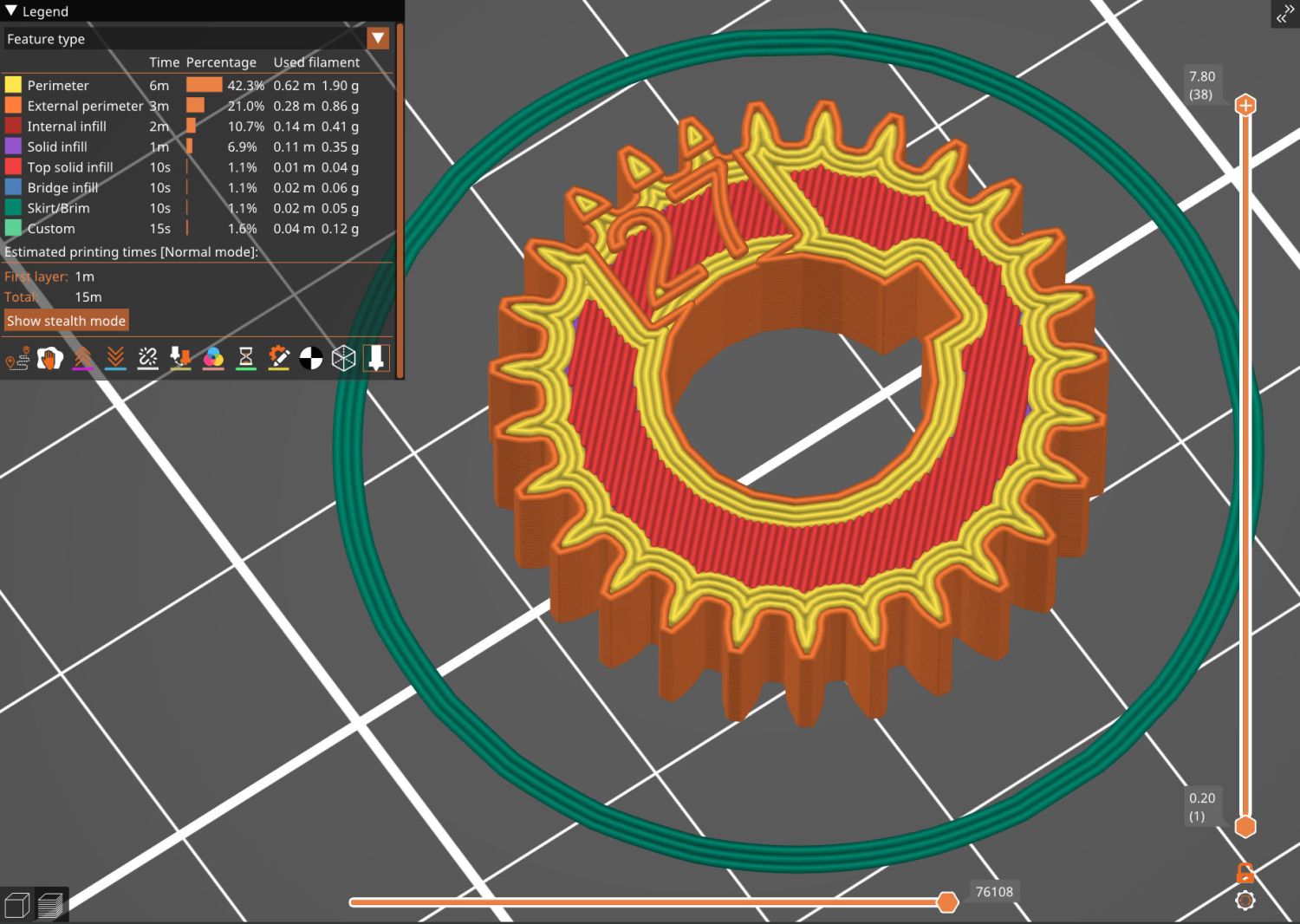

With that in mind, a home switch seemed like it might come in handy and this is the simplest workable design:

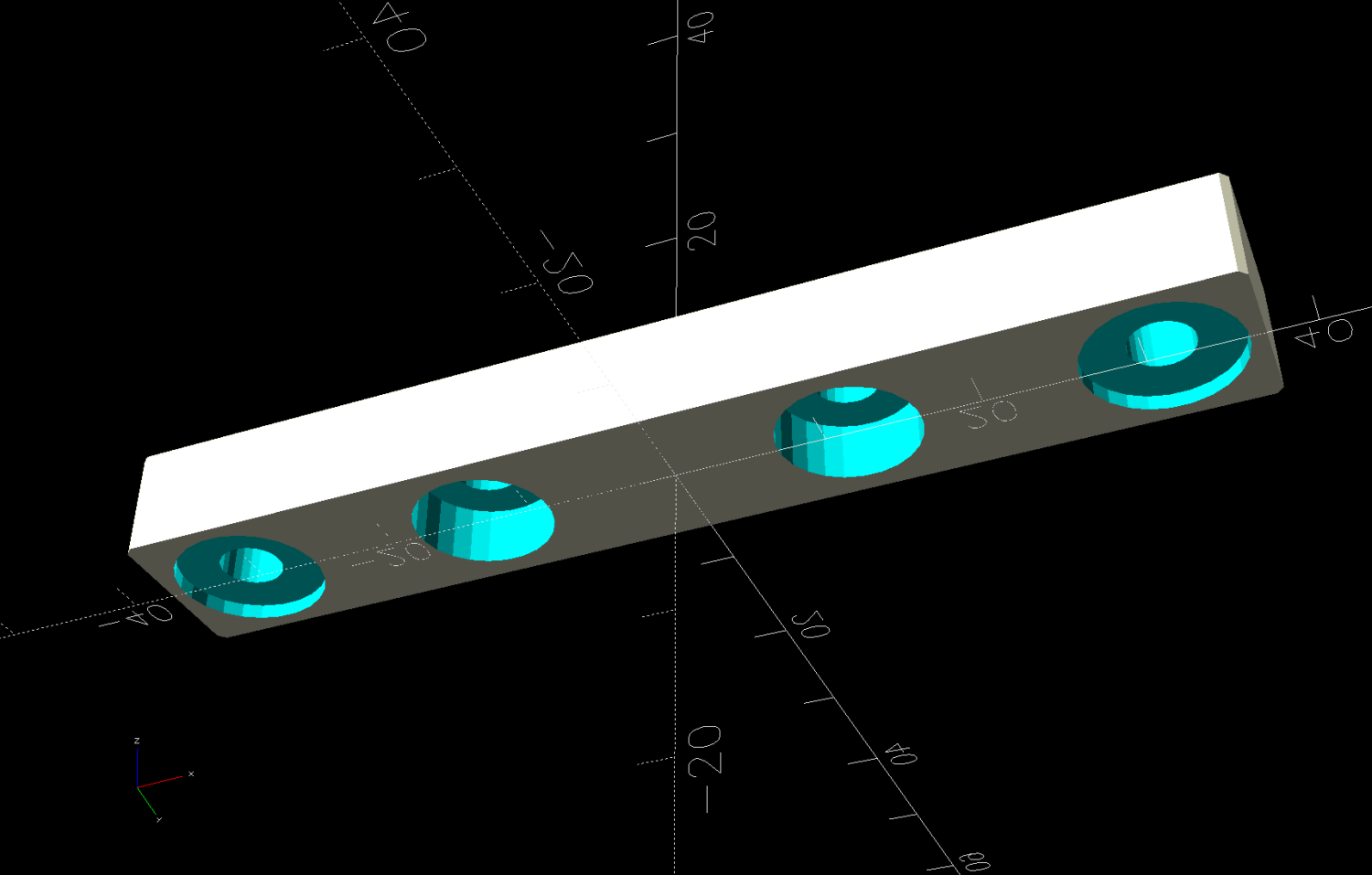

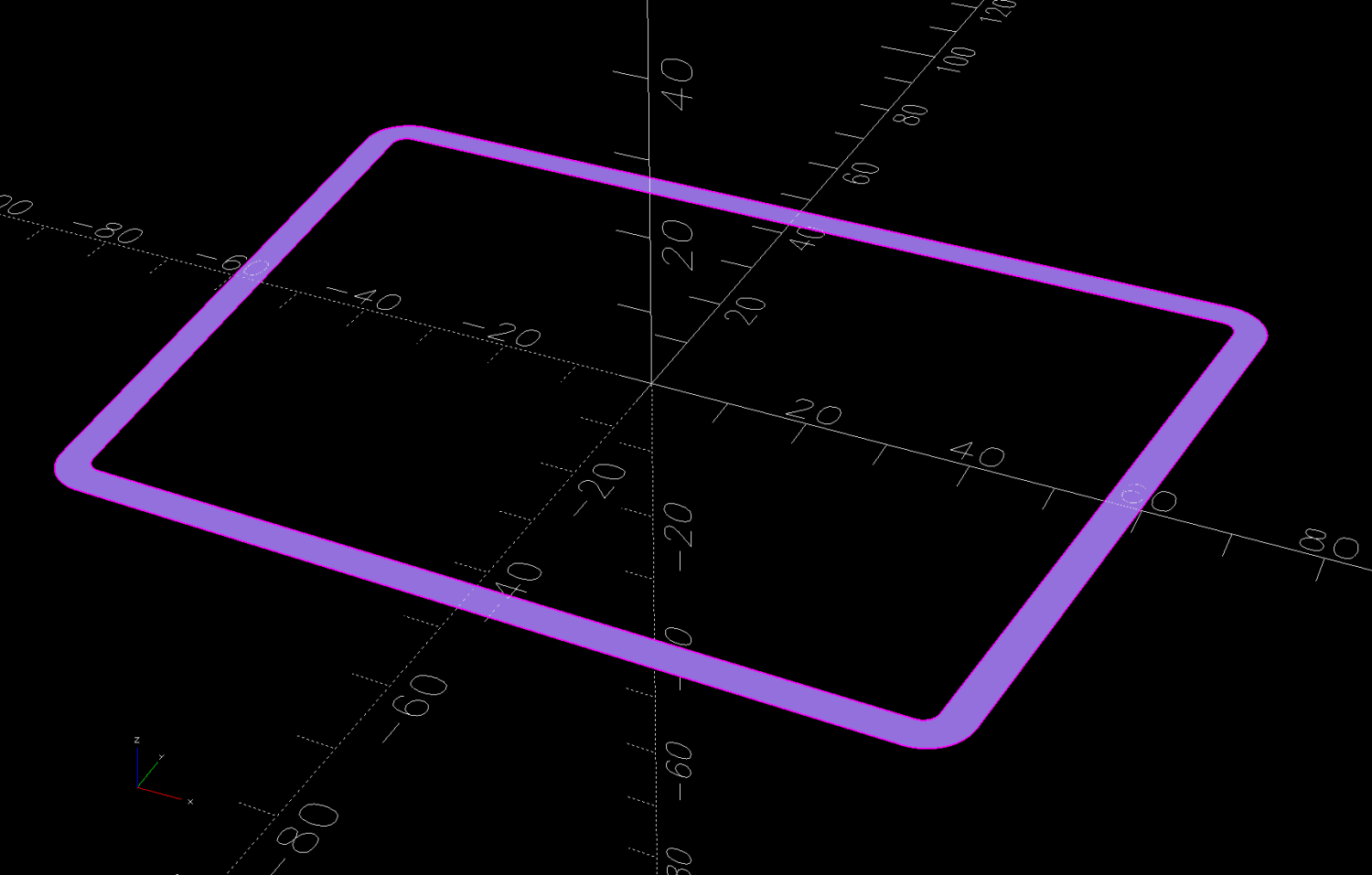

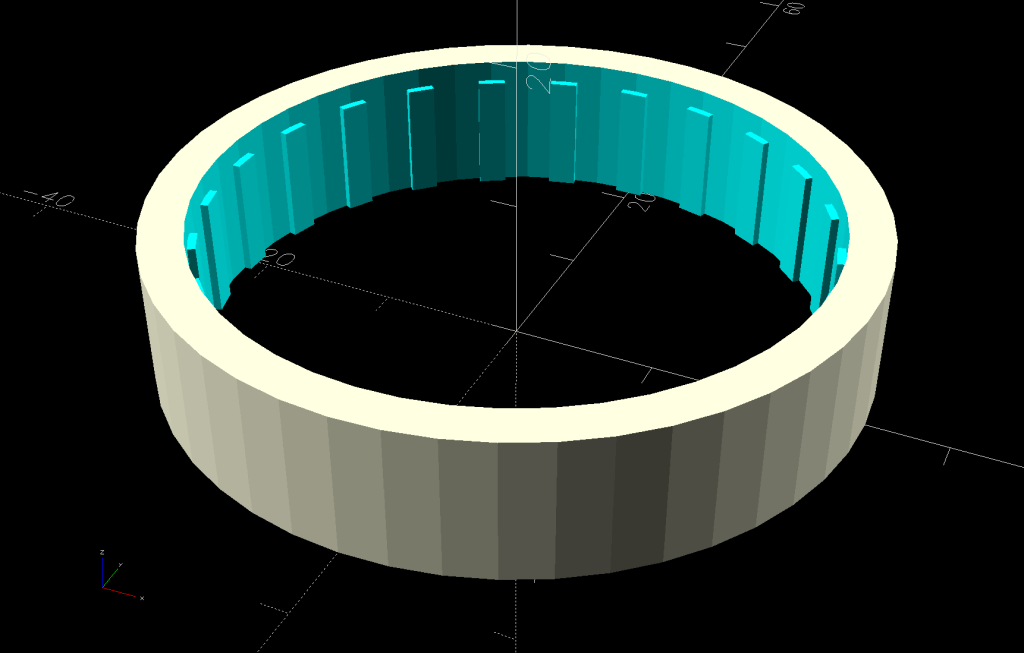

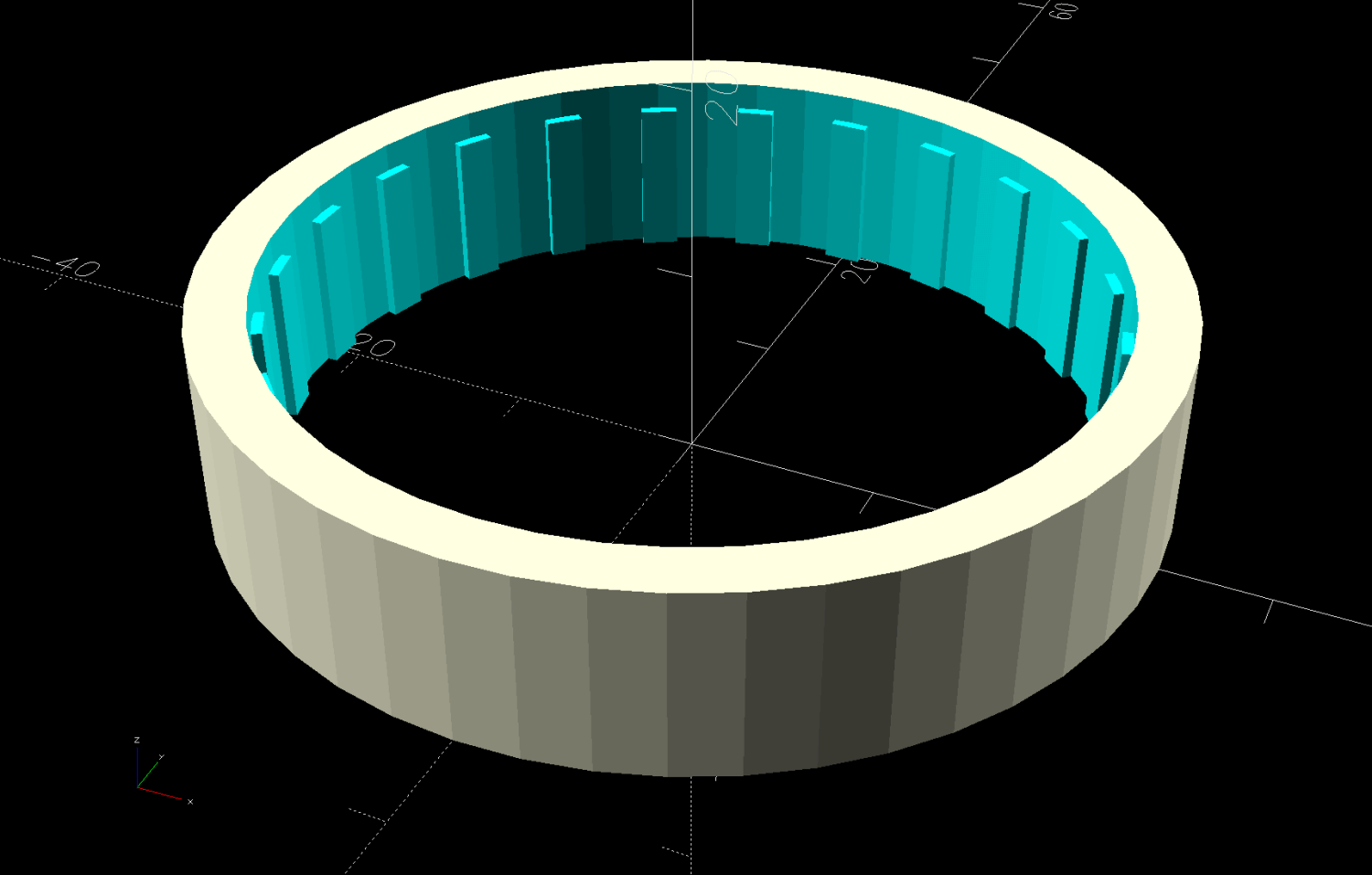

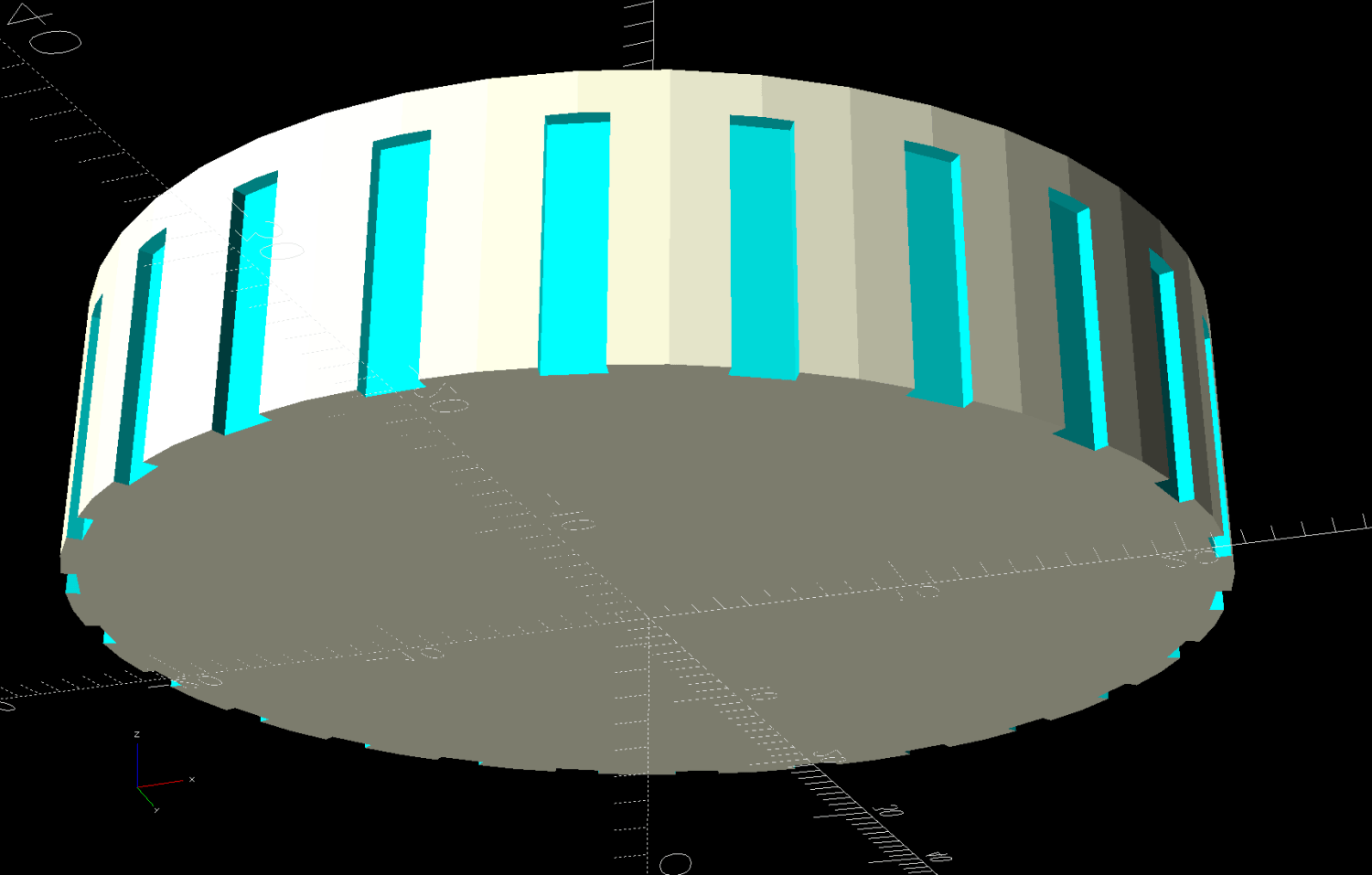

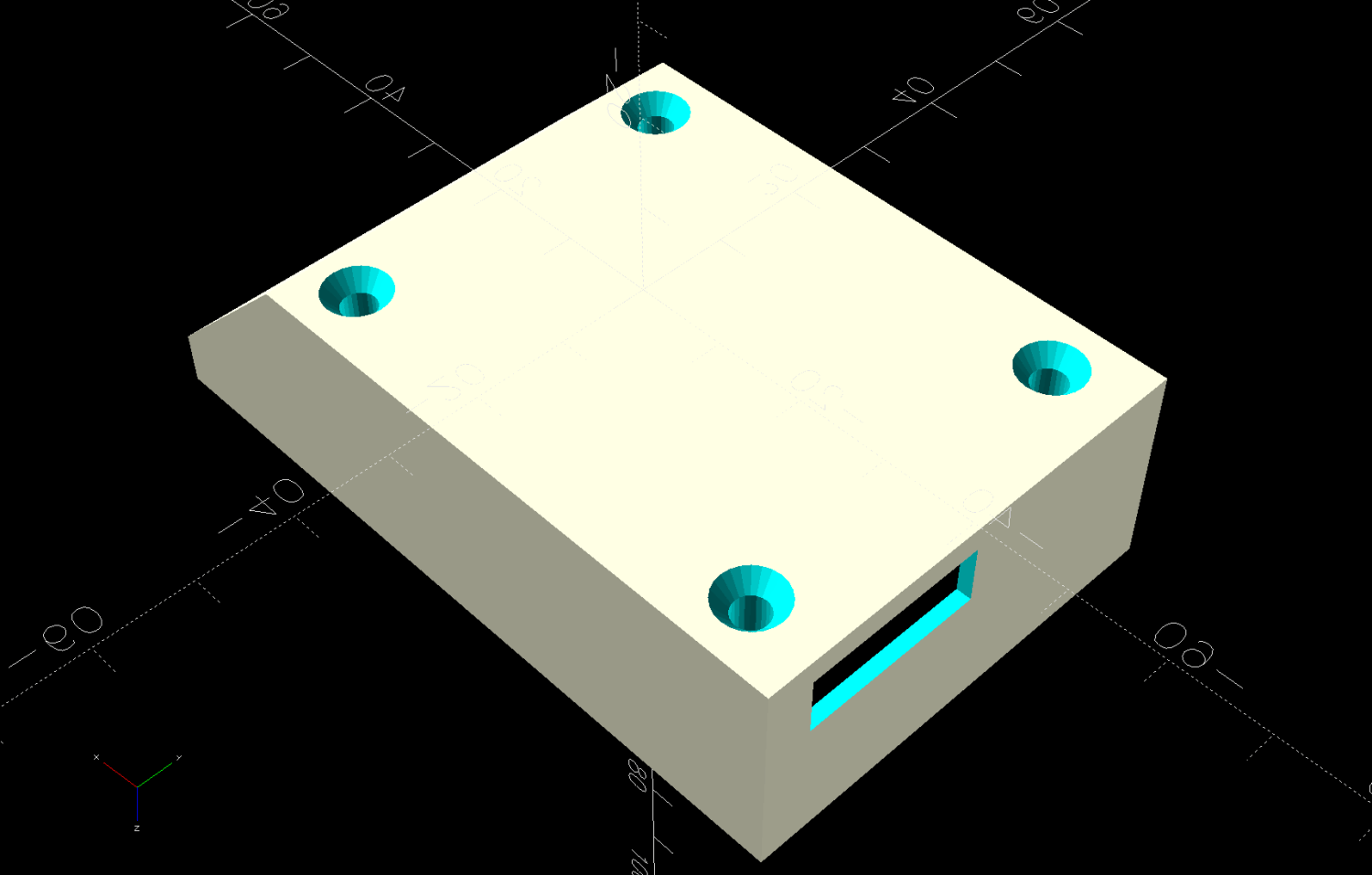

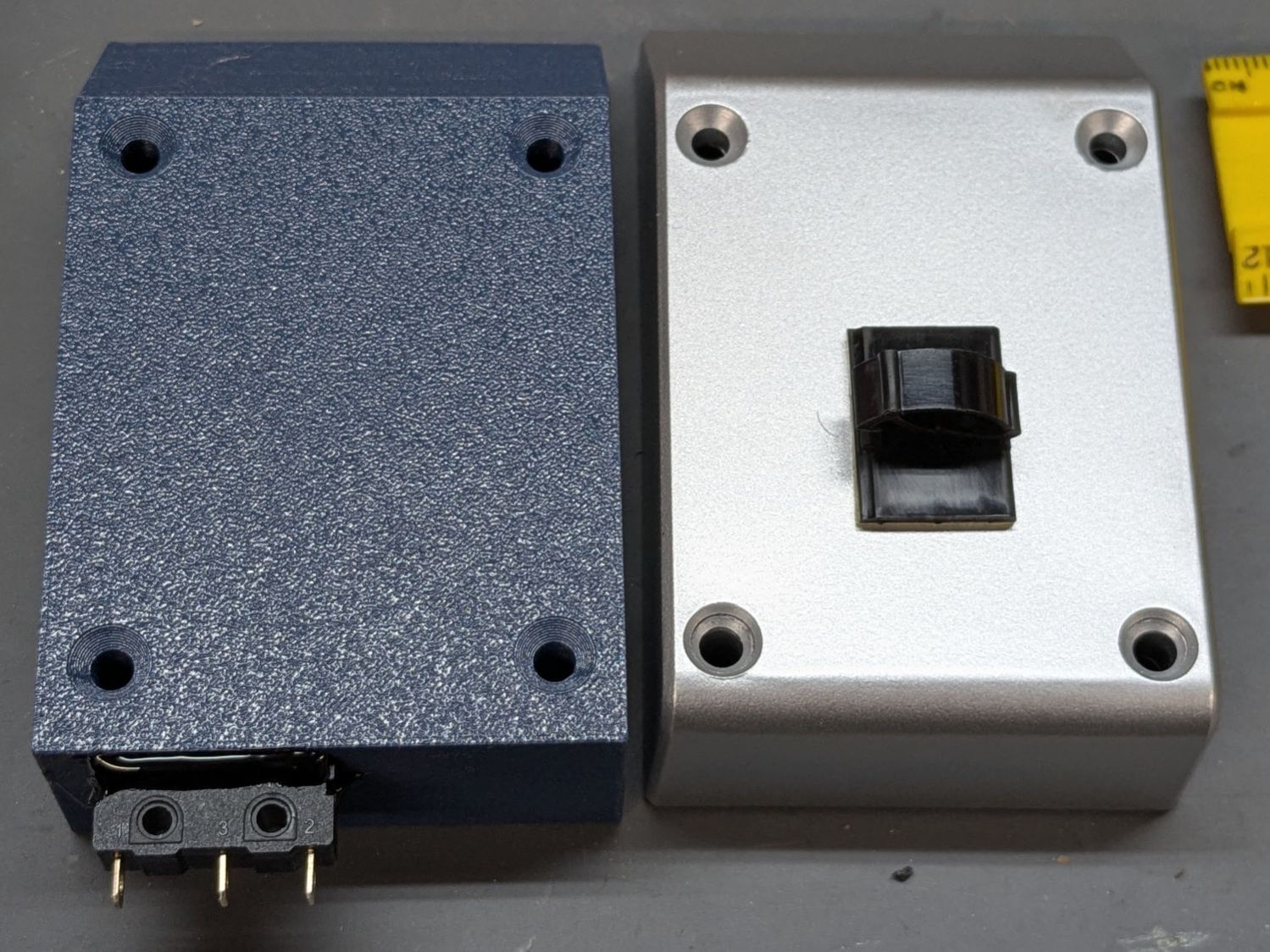

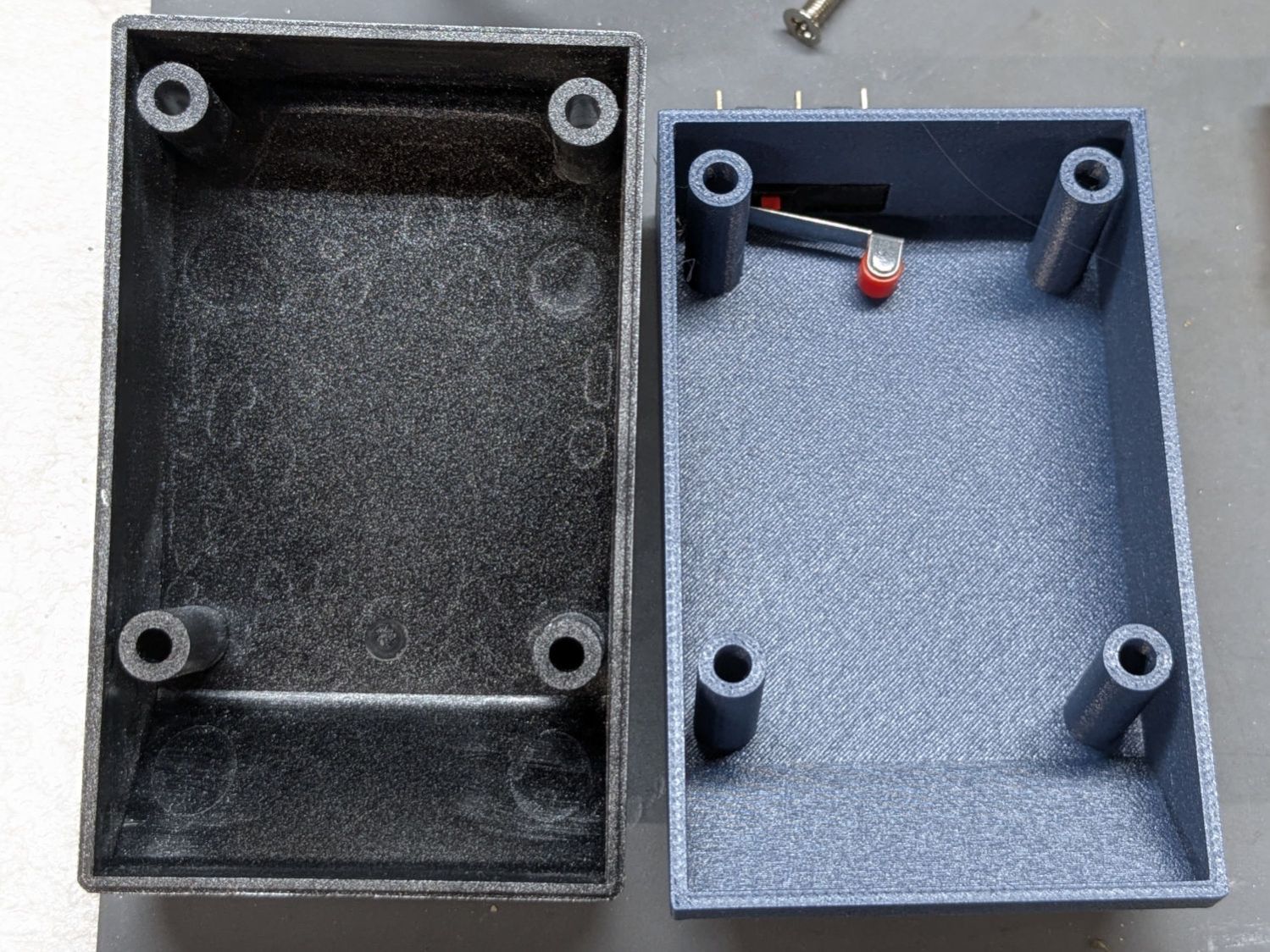

The cover mimics the size & shape of the Ortur cover, minus the stylin’ rounding & chamfering along the edges:

It has a certain Cybertruck aspect, doesn’t it?

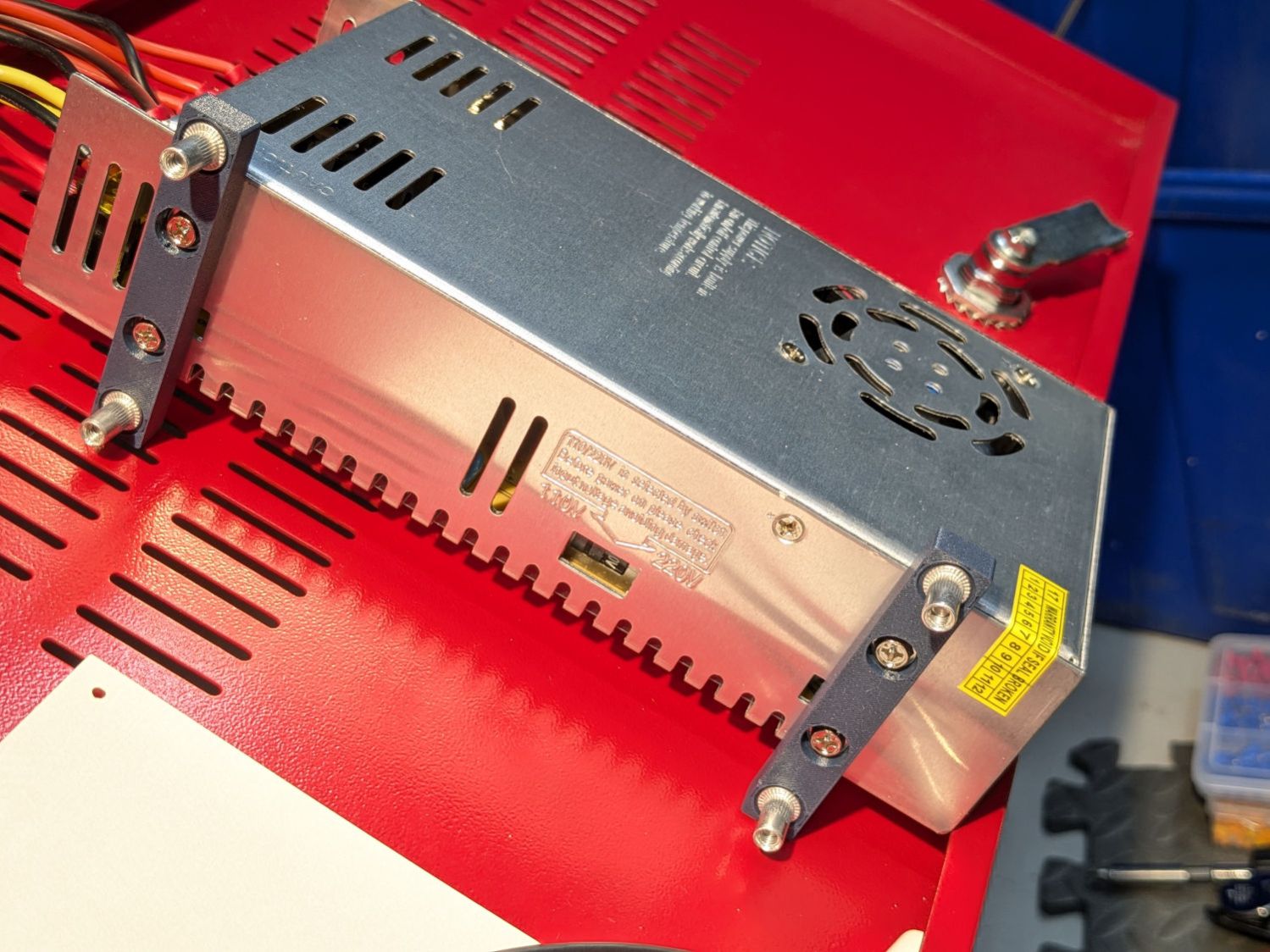

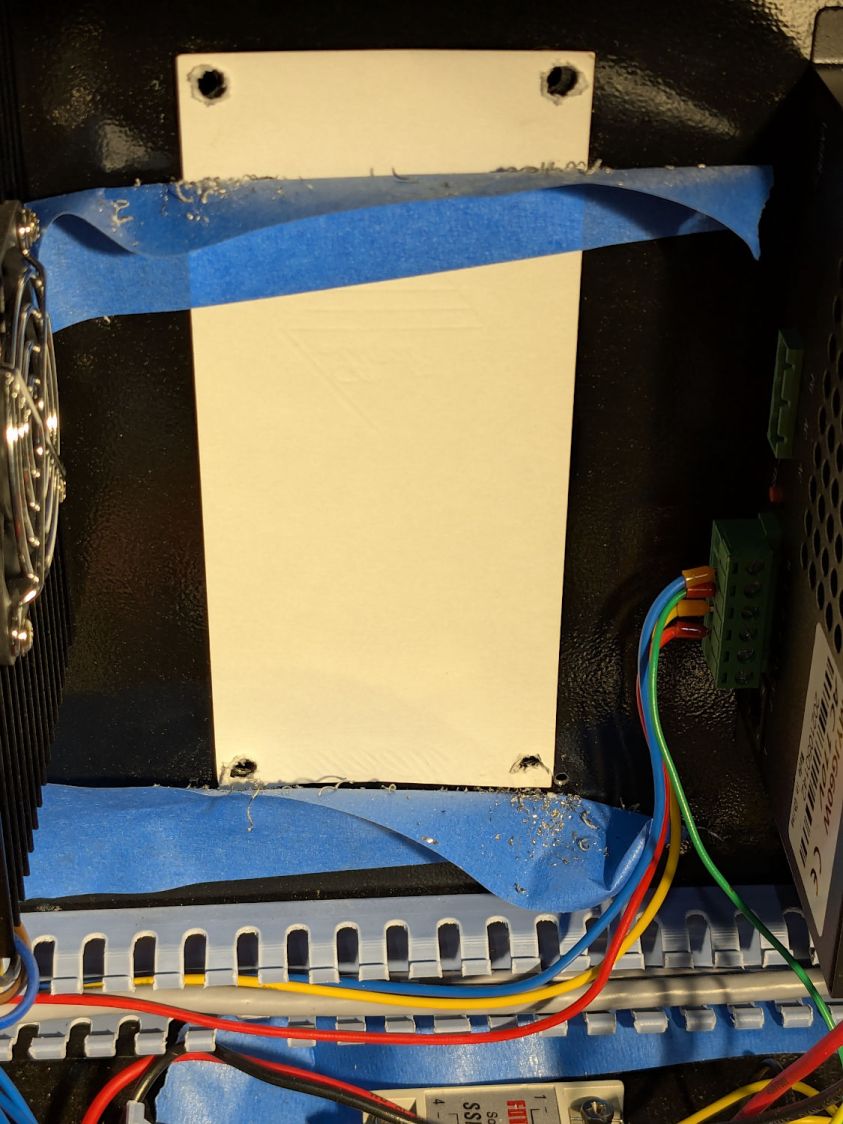

Two beads of hot melt glue hold the switch flush along the cover’s inside surface:

One might argue for a tidy cover over those terminals.

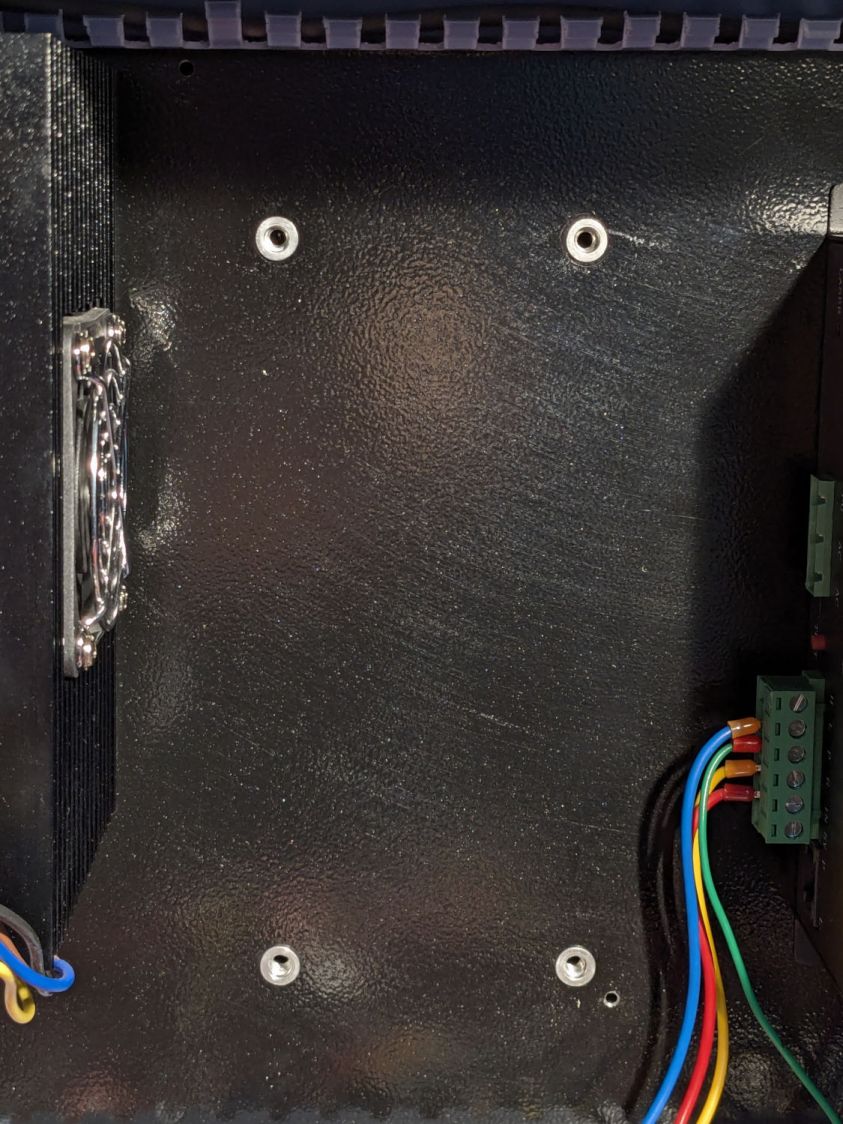

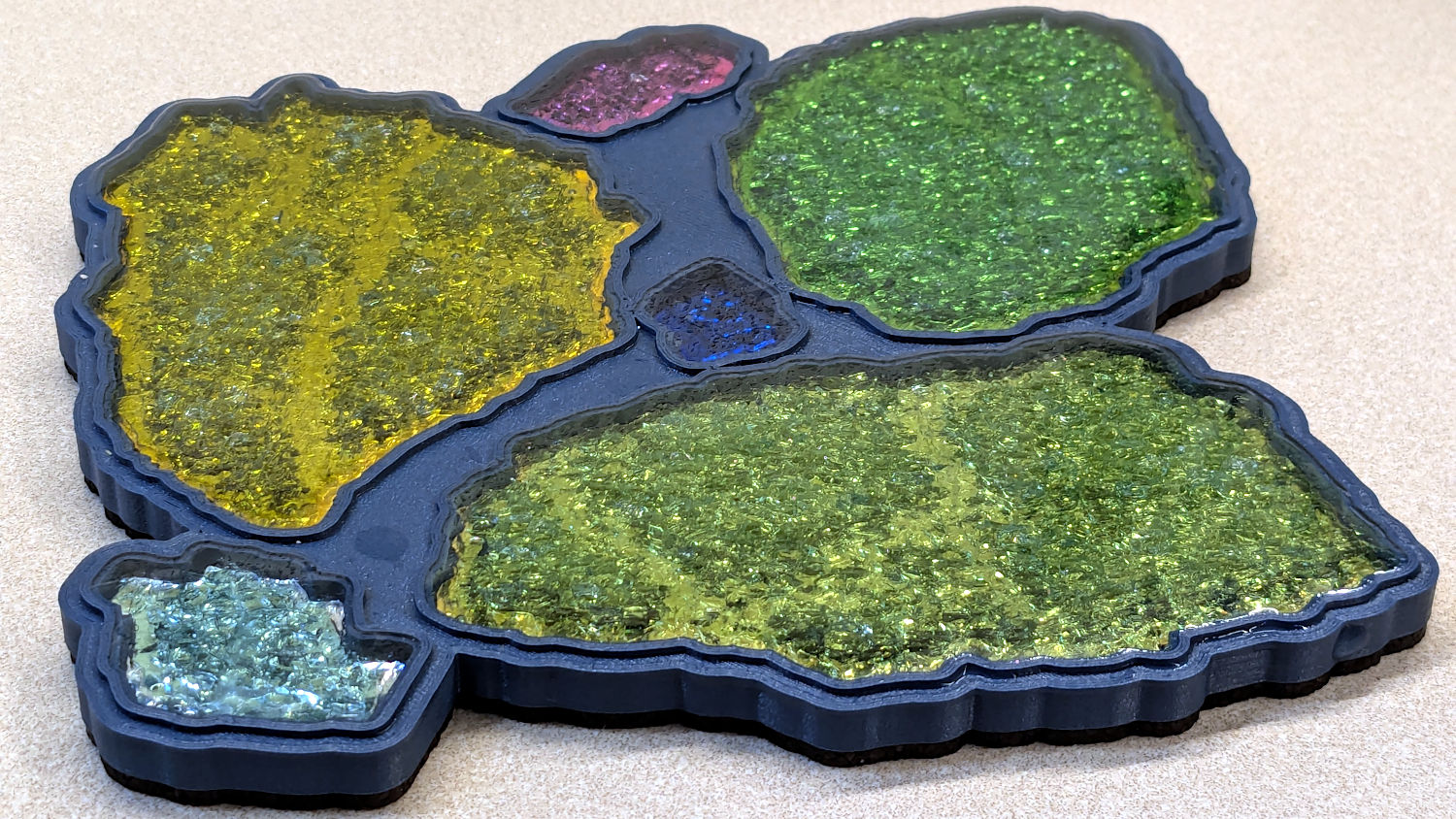

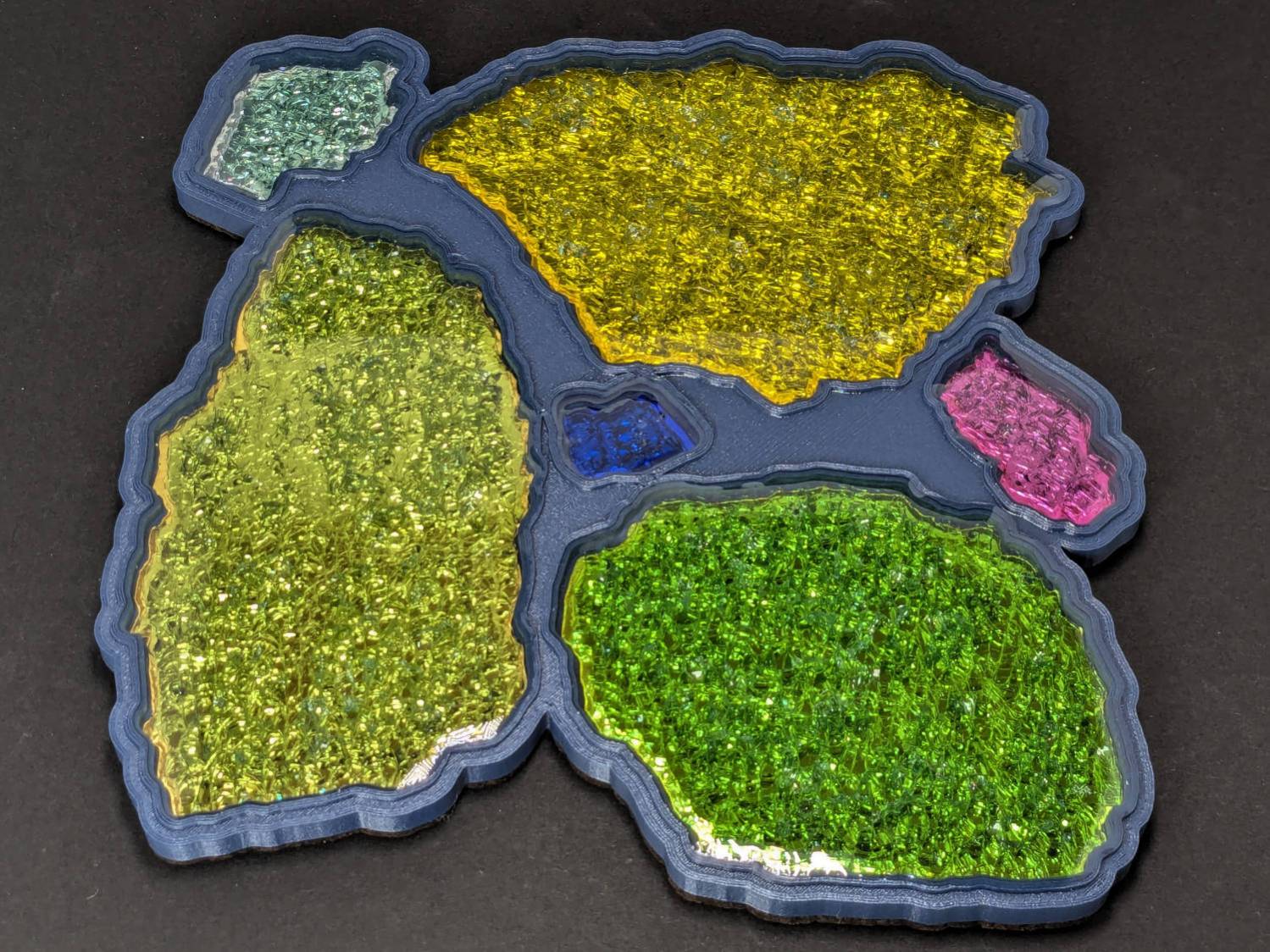

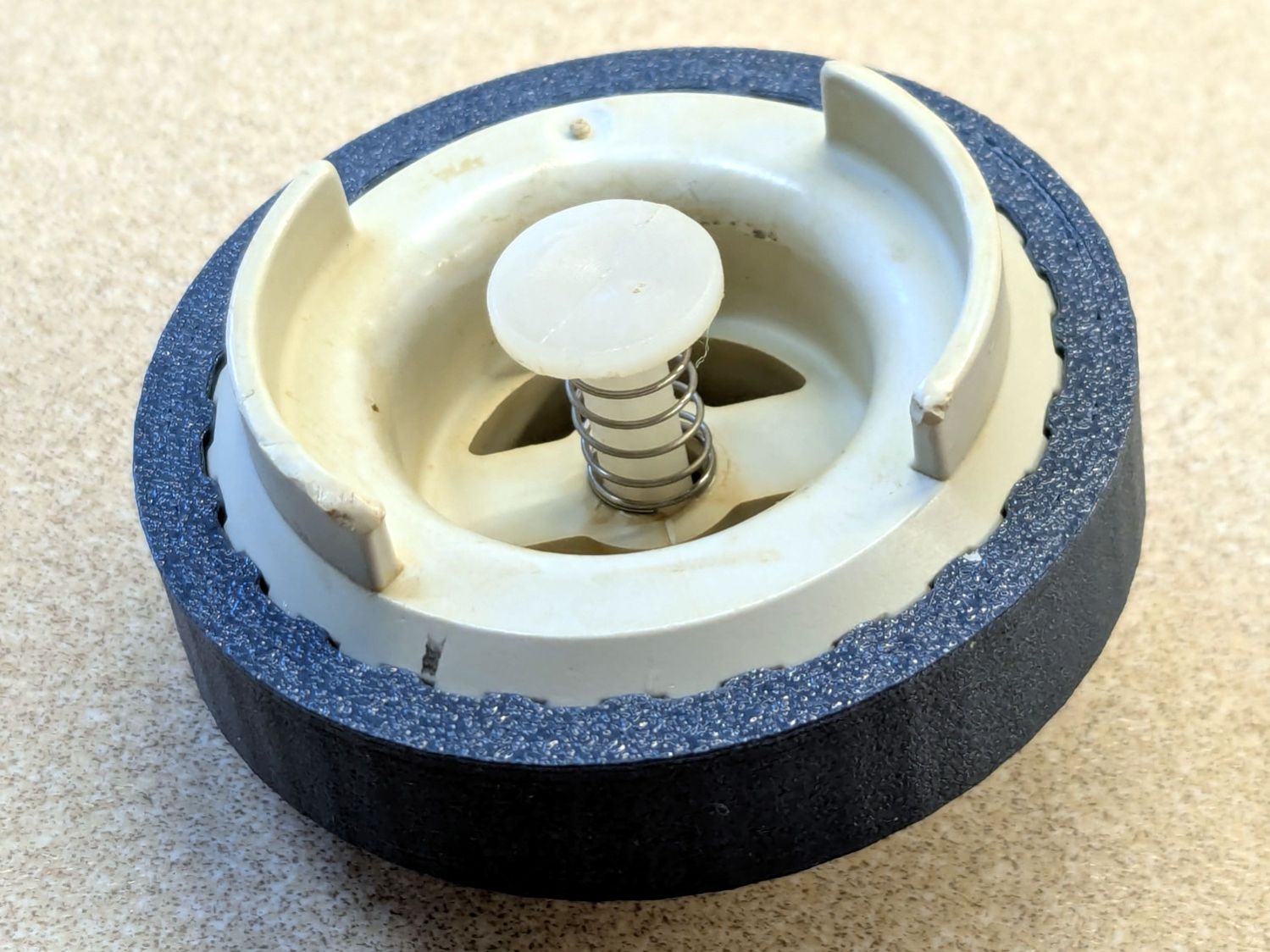

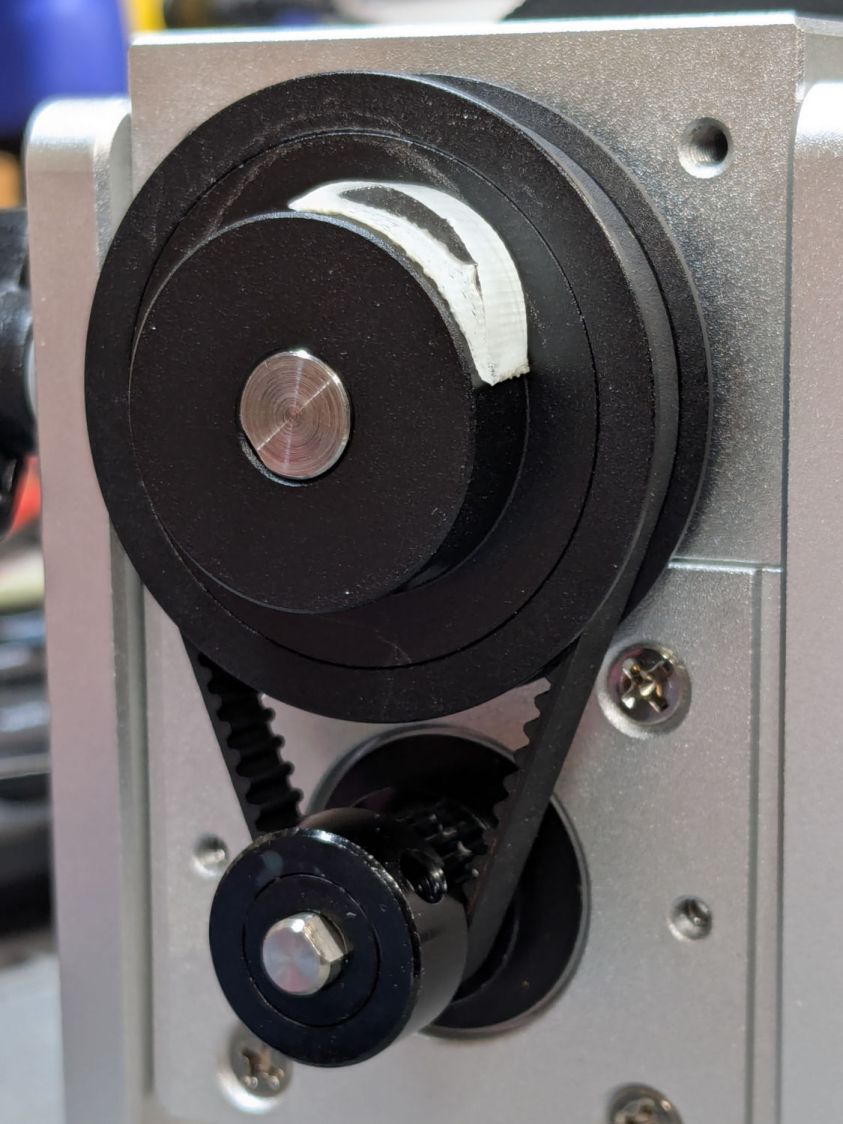

While contemplating the layout by holding the switch here & there, seeing the switch roller neatly centered on the pulley hub told me the Lords of Cosmic Jest favored this plan:

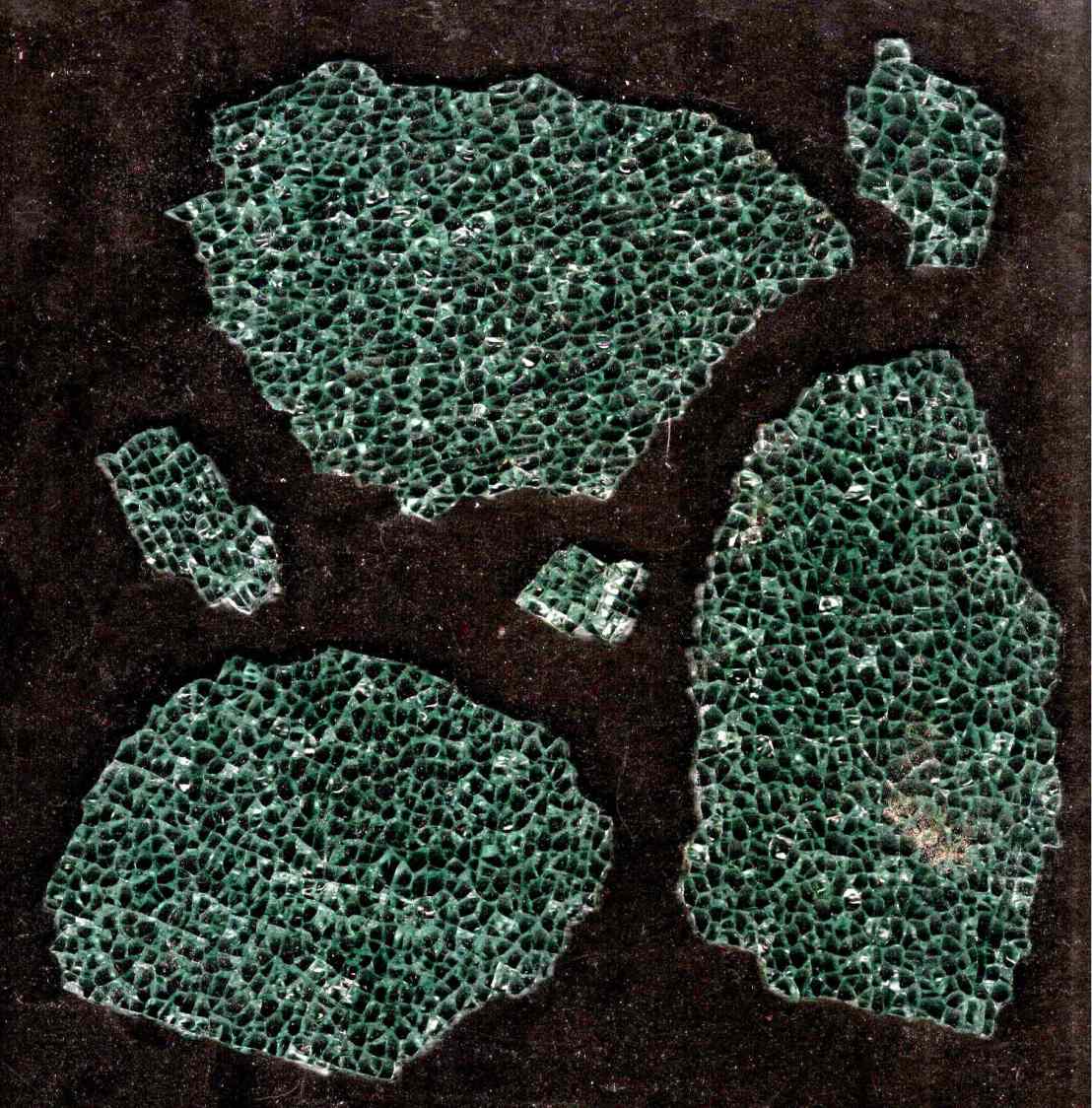

A simple cam lifts the roller:

That’s obviously laser-cut acrylic sitting on double-sided tape.

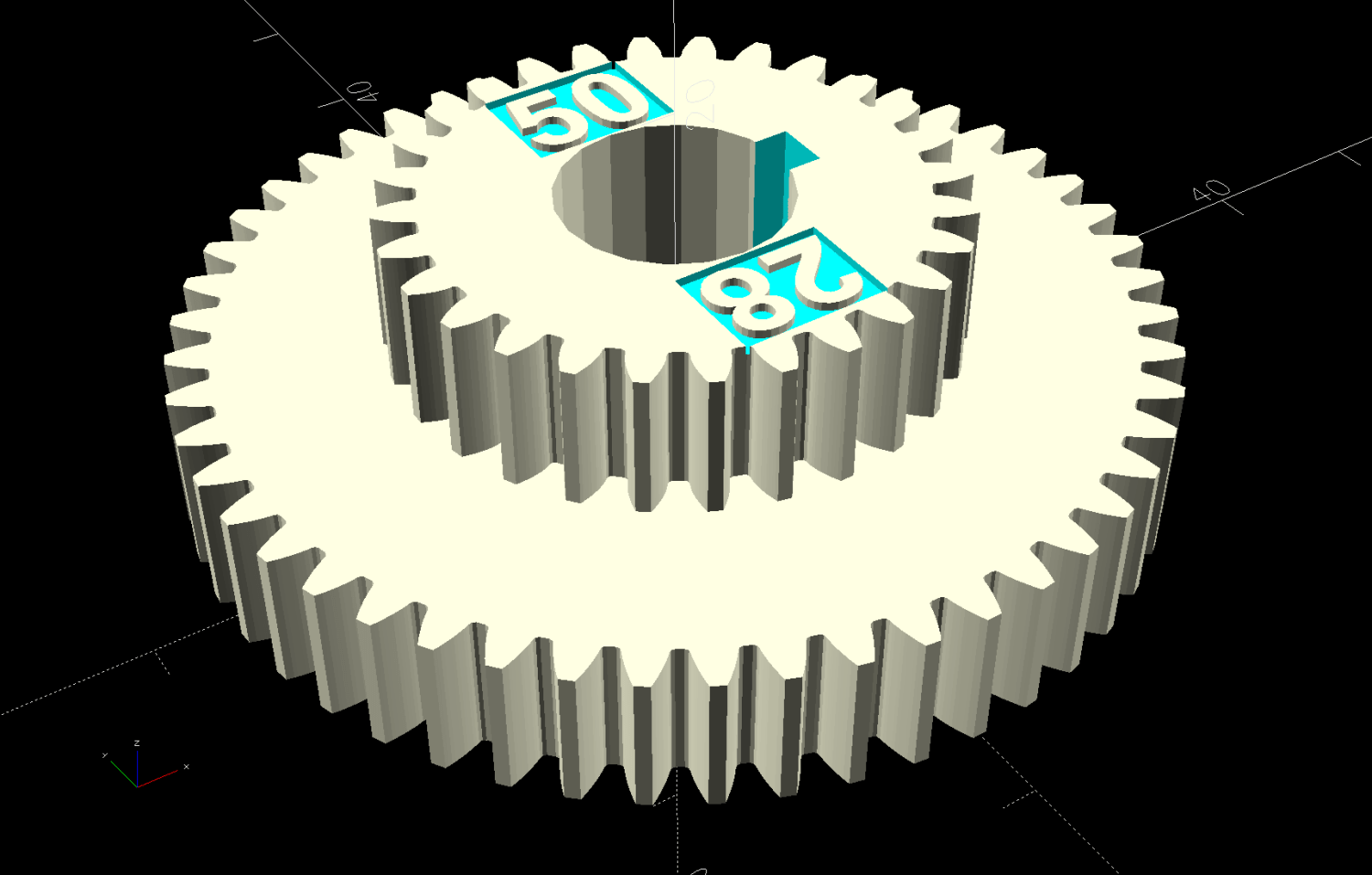

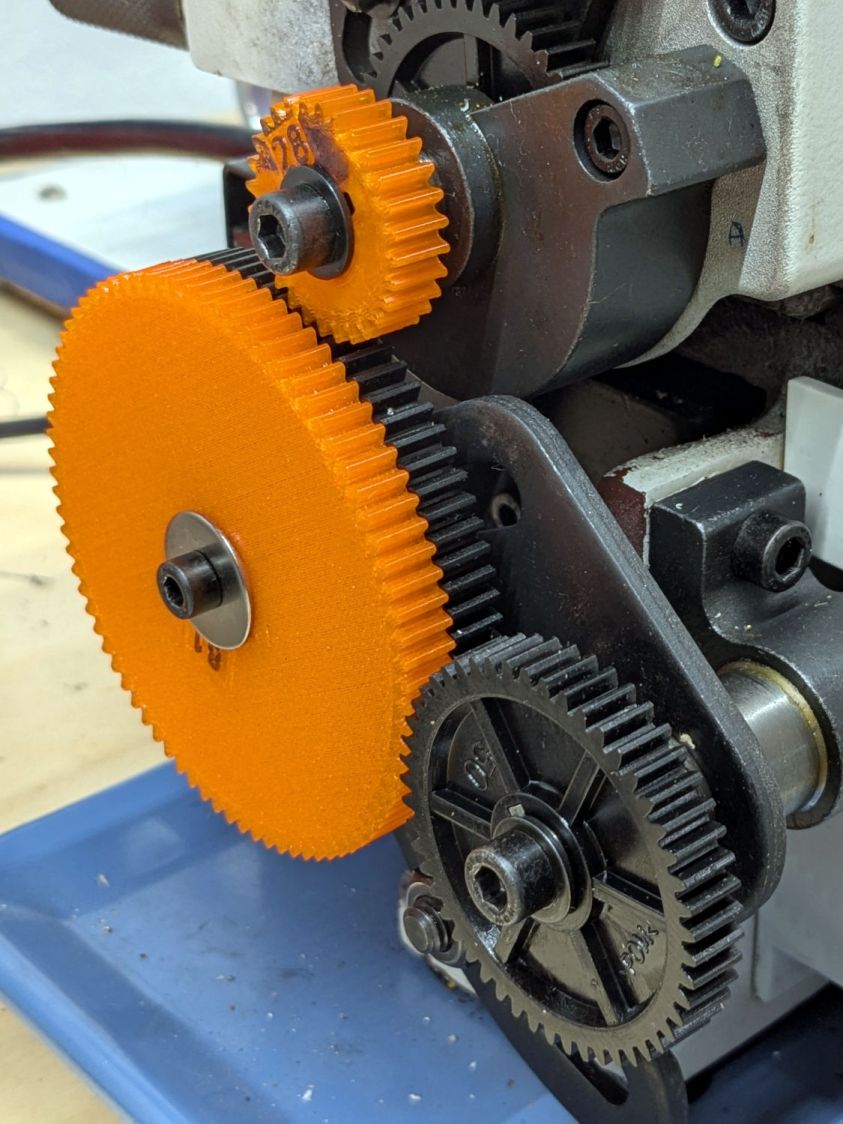

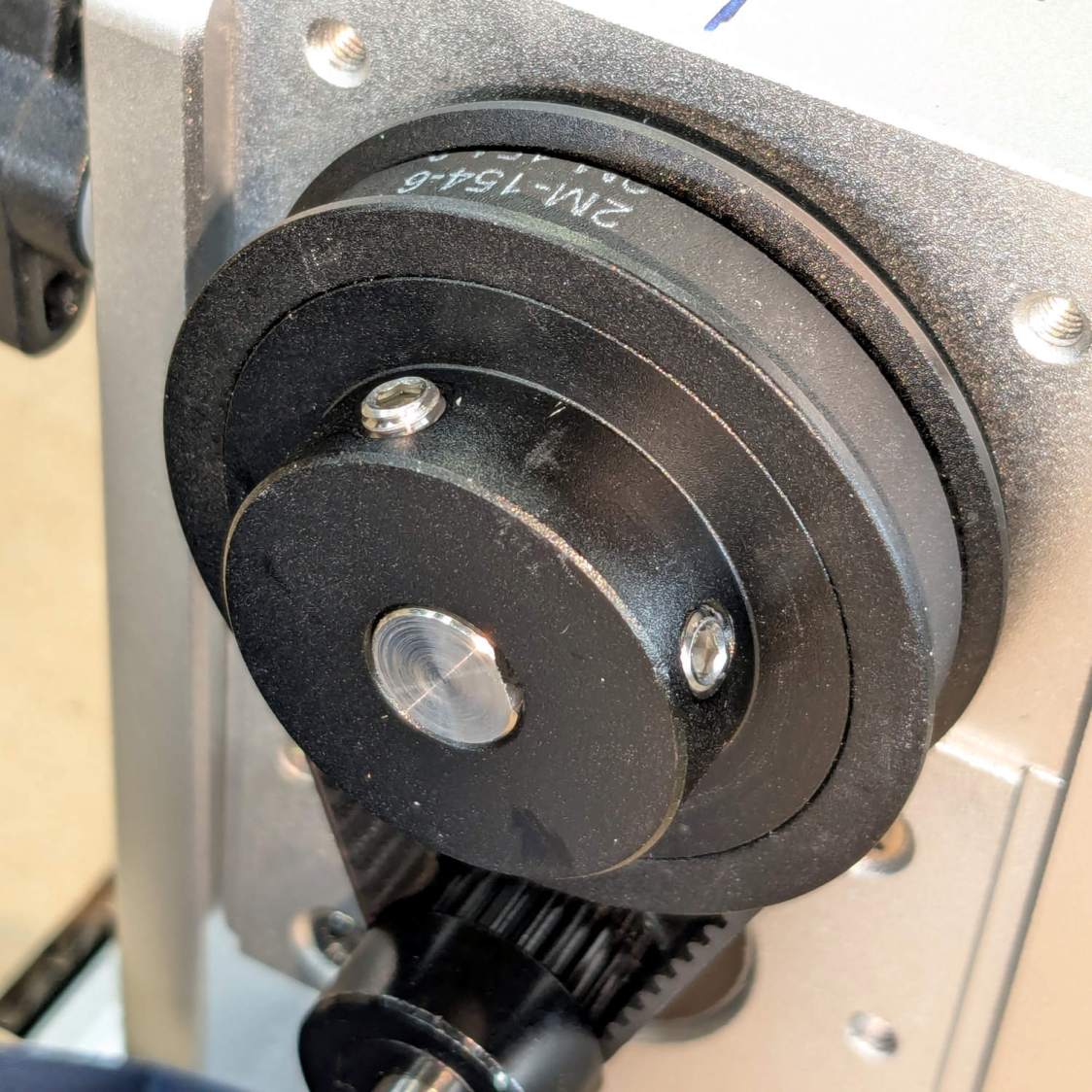

Edit: The pulley ratio is 1:3, so the step/rev value is three times the DIP switch setting on the stepper driver.

Some finicky repositioning put the #1 chuck jaw on top after homing:

A more permanent adhesive under the cam may be in order.

Update: The switch triggers more reliably with a simple setscrew standing proud of the pulley hub:

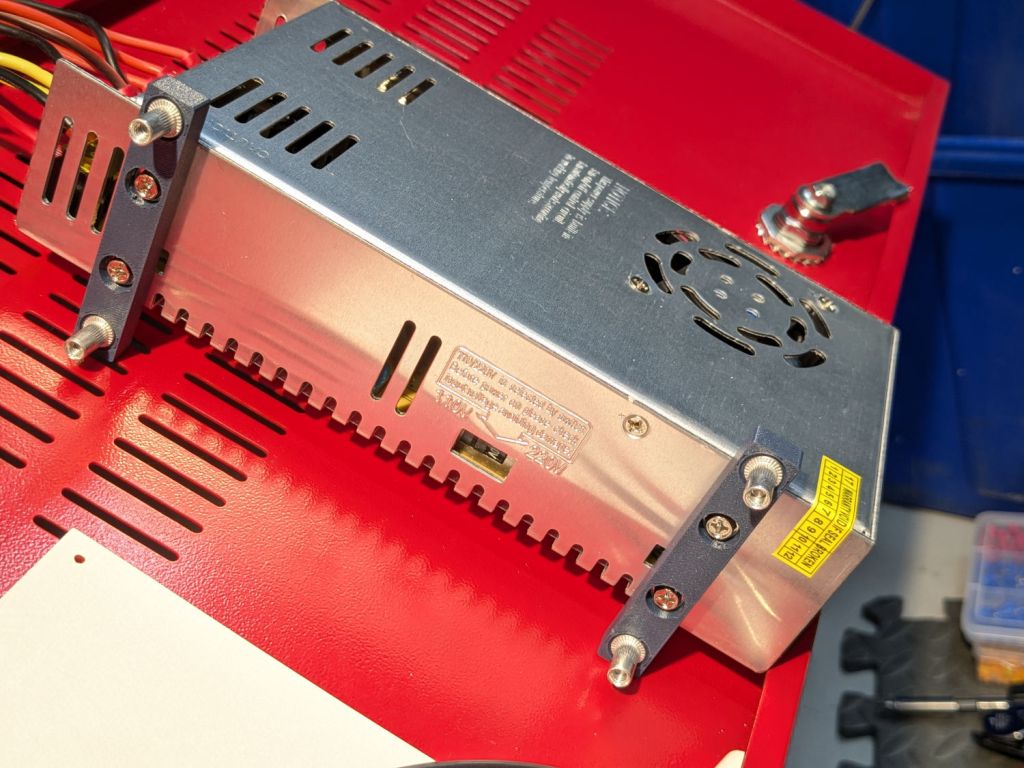

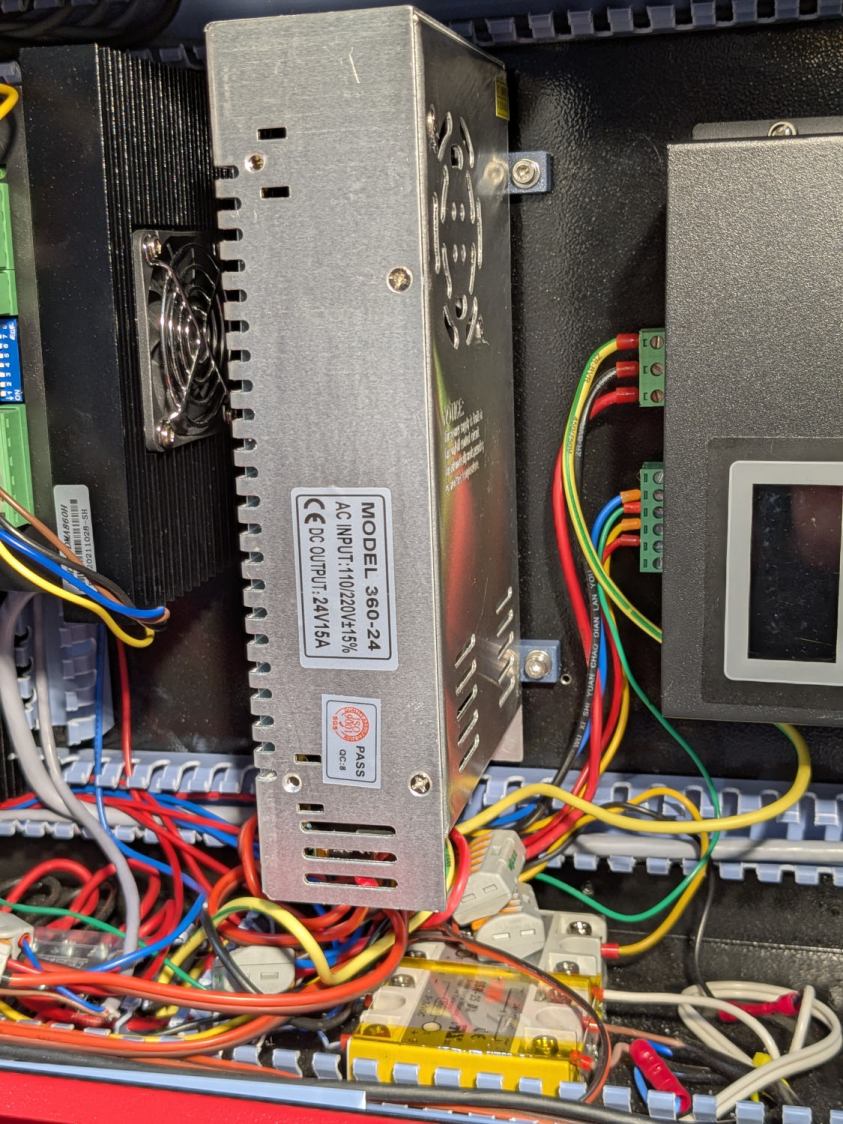

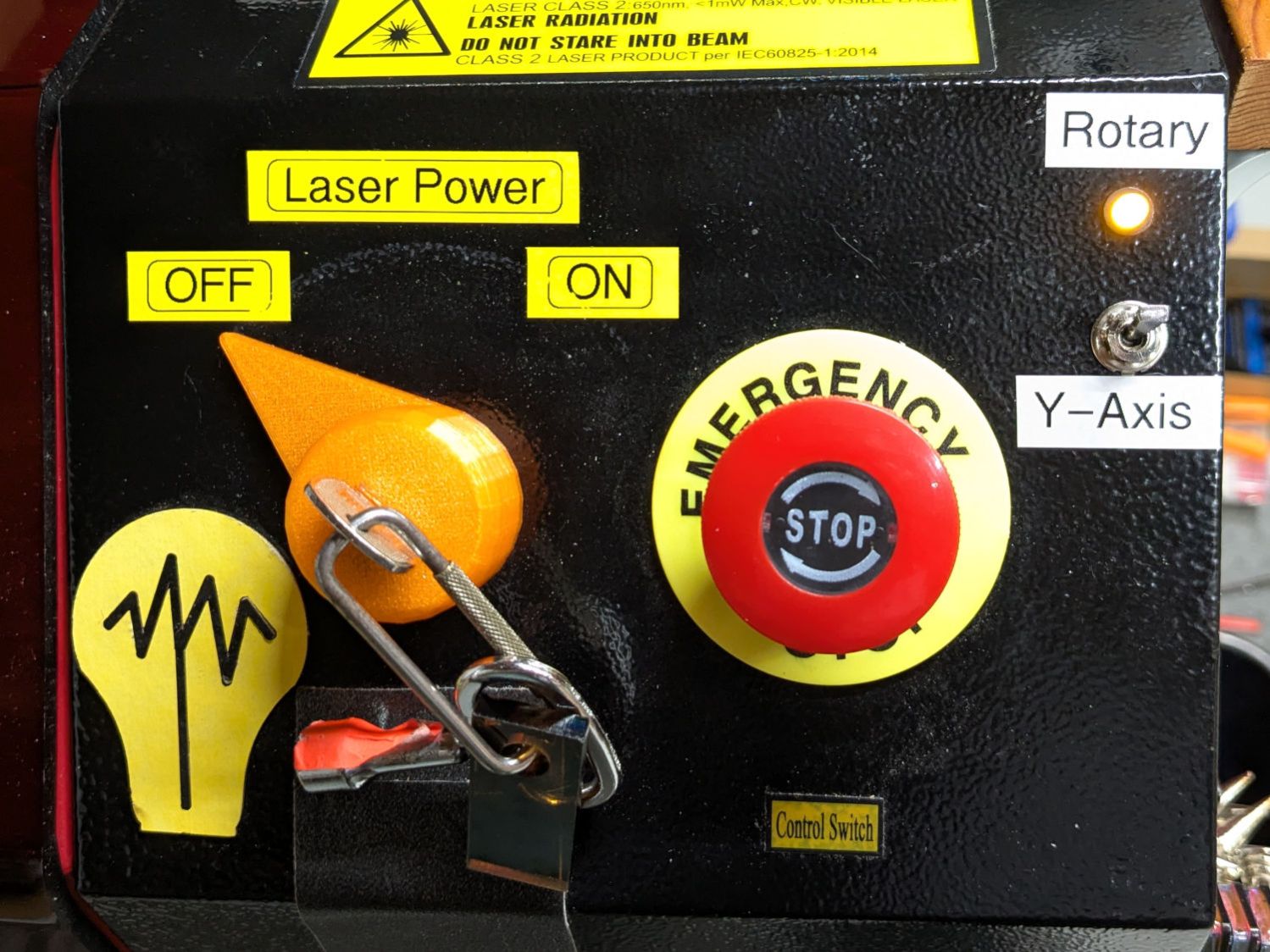

Wiring the normally open switch contacts in parallel with the existing Y axis home switch lets both the gantry and the rotary trigger the controller. The front-panel switch ensures only one of those two can move:

With all that in place and the switch flipped, the chuck rotates happily and homes properly with the controller in normal linear mode.

Spoiler: A Ruida-ish KT332N controller ignores the Y-axis Home enable setting with Rotary mode enabled, because everybody knows a rotary has no need for a home switch.

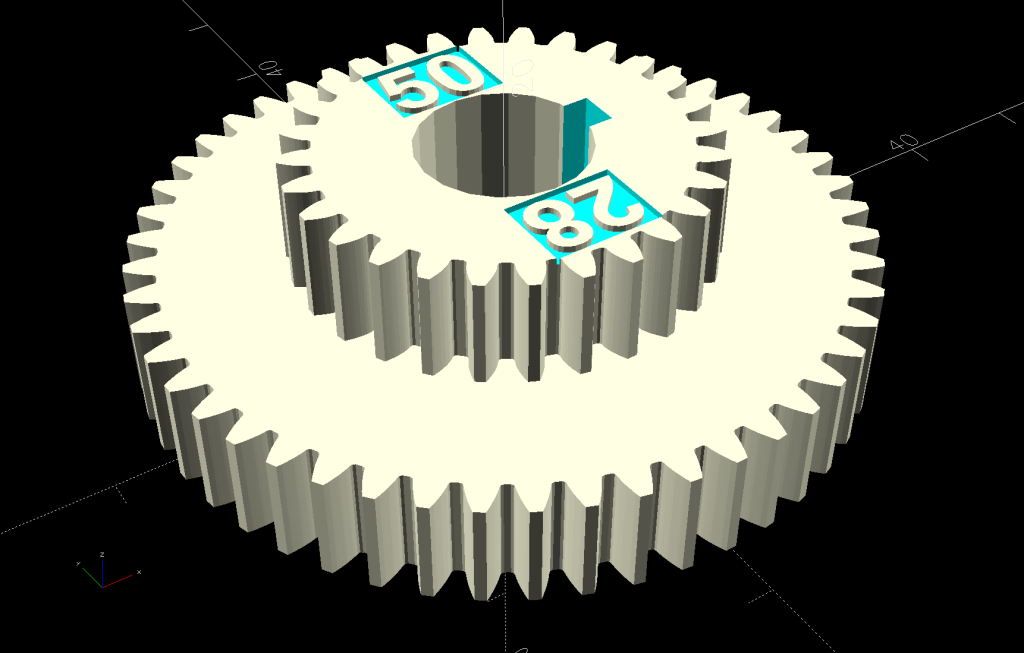

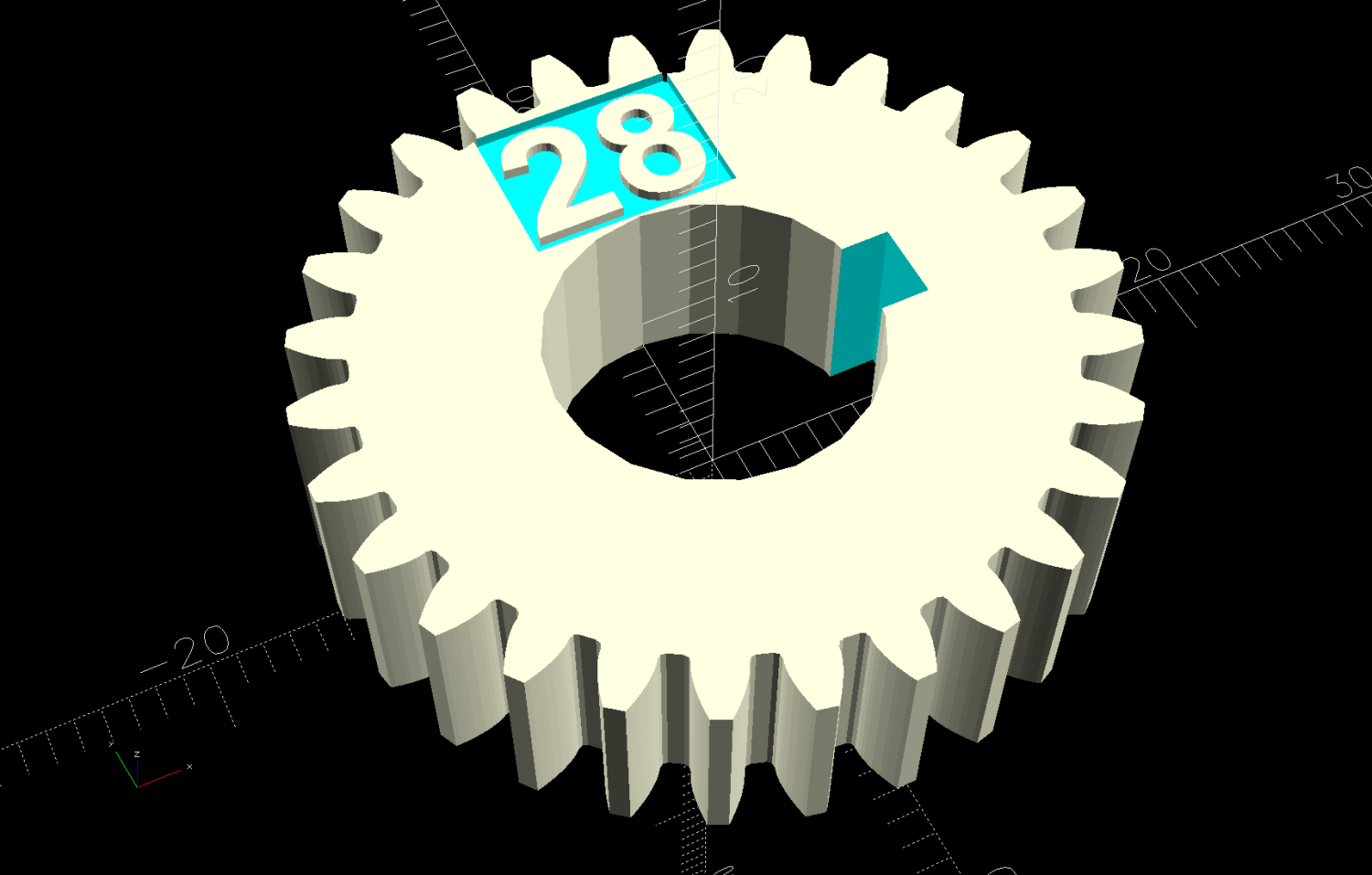

The OpenSCAD code as a GitHub Gist:

| // Ortur Rotary belt cover | |

| // Ed Nisley – KE4ZNU | |

| // 2025-12-23 | |

| include <BOSL2/std.scad> | |

| Layout = "Show"; // [Show,Build,Block,Shell] | |

| /* [Hidden] */ | |

| ID = 0; | |

| OD = 1; | |

| LENGTH = 2; | |

| HoleWindage = 0.2; | |

| Protrusion = 0.1; | |

| NumSides = 2*3*4; | |

| $fn=NumSides; | |

| Gap = 5.0; | |

| WallThick = 1.6; // OEM wall | |

| CoverOA = [81.5,50.5,23.0]; // open side down | |

| CoverRadius = 4.0; | |

| CoverTrimZ = 6.0; | |

| CoverTrimAngle = 45; | |

| BreakX = (CoverOA.z – CoverTrimZ)/tan(CoverTrimAngle); | |

| ScrewOC = [51.0,38.0]; | |

| ScrewHoleID = 3.5; | |

| ScrewHeadRecess = [ScrewHoleID,7.0,1.8]; | |

| ScrewOffset = 8.0; // cover edge to hole centerline | |

| SwitchOA = [21.0,20.0,6.5]; // X = body + roller, excludes terminals | |

| SwitchOffset = [0,0,17.0]; // nominal end = roller at centerline | |

| //—– | |

| // Overall cover shape | |

| module CoverBlock() { | |

| cuboid([CoverOA.x,CoverOA.y,CoverTrimZ],anchor=BOTTOM) position(TOP+LEFT) | |

| prismoid(size1=[CoverOA.x,CoverOA.y],size2=[CoverOA.x – BreakX,CoverOA.y], | |

| height=CoverOA.z – CoverTrimZ,shift=[-BreakX/2,0],anchor=BOTTOM+LEFT); | |

| } | |

| // Cover shell | |

| module CoverShell() { | |

| difference() { | |

| CoverBlock(); | |

| down(Protrusion) | |

| resize(CoverOA – [2*WallThick,2*WallThick,WallThick – Protrusion]) | |

| CoverBlock(); | |

| } | |

| } | |

| // The complete cover | |

| module Cover() { | |

| difference() { | |

| union() { | |

| CoverShell(); | |

| left((CoverOA.x – ScrewOC.x)/2 – ScrewOffset) | |

| for (i = [-1,1], j=[-1,1]) | |

| translate([i*ScrewOC.x/2,j*ScrewOC.y/2,0]) | |

| cyl(CoverOA.z,d=ScrewHoleID + 2*WallThick,anchor=BOTTOM); | |

| } | |

| left((CoverOA.x – ScrewOC.x)/2 – ScrewOffset) down(Protrusion) | |

| for (i = [-1,1], j=[-1,1]) | |

| translate([i*ScrewOC.x/2,j*ScrewOC.y/2,0]) { | |

| cyl(CoverOA.z + 2*Protrusion,d=ScrewHoleID + HoleWindage,anchor=BOTTOM); | |

| up(CoverOA.z – ScrewHeadRecess[LENGTH]) | |

| cyl(ScrewHeadRecess[LENGTH] + 2*Protrusion, | |

| d1=ScrewHeadRecess[ID] + HoleWindage,d2=ScrewHeadRecess[OD] + HoleWindage, | |

| anchor=BOTTOM); | |

| } | |

| translate(SwitchOffset) left(CoverOA.x/2 – WallThick – Protrusion) | |

| cuboid(SwitchOA,anchor=RIGHT+FWD); | |

| } | |

| } | |

| //—– | |

| // Build things | |

| if (Layout == "Block") { | |

| CoverBlock(); | |

| } | |

| if (Layout == "Shell") { | |

| CoverShell(); | |

| } | |

| if (Layout == "Show") { | |

| Cover(); | |

| } | |

| if (Layout == "Build") { | |

| up(CoverOA.z) | |

| xrot(180) | |

| Cover(); | |

| } | |