We don’t drive the van nearly often enough (*) to keep the battery charged in cold weather, so I use a trickle charger to keep it alive between jaunts. While opening the hood one evening, I managed to twist the plastic fitting that anchors the hood prop rod beyond its limits and snapped the poor thing off, which left me holding the hood in one hand and the rod in the other.

After extricating most of the fragments from under the van, I found that the OEM part had a hollow post that snapped into a square hole in the front bulkhead under the hood. The post had two keys and a pair of snap latches that held it in place, a design that seemed optimized for rapid assembly with no fiddly parts, but which depended on a few millimeters of plastic to restrain a meter of steel rod.

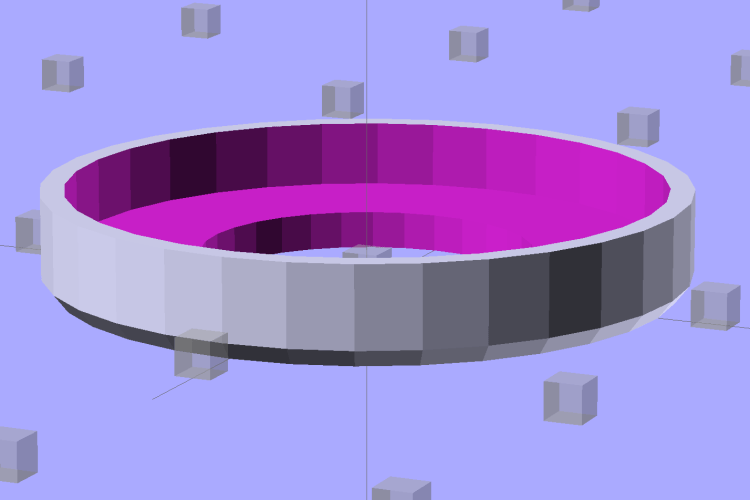

I made up a simple replacement with a solid square post and a square cap to clamp it against the bulkhead:

The general idea is that the screw puts the entire post under compression, giving it less temptation to shear at the deck line when I twist the rod a bit too far out of line. That 8-32 screw seemed entirely adequate to the task; a 10-32 screw would take up too much of the post for my liking.

Alas, it turns out that underneath the bulkhead’s top flange lies a metal plate surrounding the headlight that’s so close to the hole that the big blocky cap wouldn’t fit. So I slimmed the cap down to three thread widths and tried again, only to discover that the plate came that close to the edge of square hole.

However, there was a gap between the bottom of the bulkhead and the top of the plate, so I introduced pivot and cap to Mr Belt Sander, removed enough plastic to let the cap slide into the gap, then discovered the 8-32 screw head was just slightly too large to let the screw align with the post.

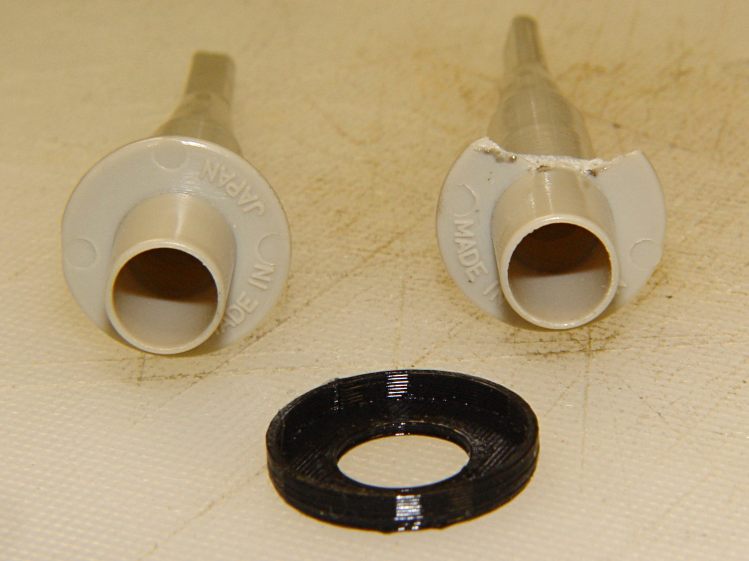

Another tweak to the model, based on actual measurements on the abused parts, produced the final version:

The rod hole has a nice bevel, there’s no fragile neck between the rod hole and the base flange, the solid post lies flat on the platform for EZ building, and there’s a slight offset between the post and the flange that eliminates the need for support material. Printing it lying down orients the filament paths around the hole and base, making the part stronger in the direction it needs the most strength.

I think the cap walls could be slightly thicker, but we’ll see how long the thing lasts…

A group photo of all the versions, lined up from left to right, shows the broken OEM part, the first blocky attempt, the slimmed-down and too-long version to the rear, the shorter version that actually fit, and a backup part for when that one breaks:

The sanded-down part held the hood open while I took that group picture. Here’s what it looks like under load:

The scrawls on the bulkhead just in front of the pivot remind me of fluid levels, torques, and suchlike. The stud sticking out to the rear is a headlight aiming screw mounted in the plate that caused so much hassle; you’d think I’d have noticed it before starting this adventure, but noooo…

For what it’s worth, that’s rapid prototyping in action: three (and a half) iterations in quick succession, each getting closer to a goal that you (well, I) can’t quite define, but will recognize when it appears. Took about three hours over the course of two days.

I loves me my M2 3D printer…

(*) Indeed, the tires often take three miles to warm up their flat spots due to sitting in the garage for a week…