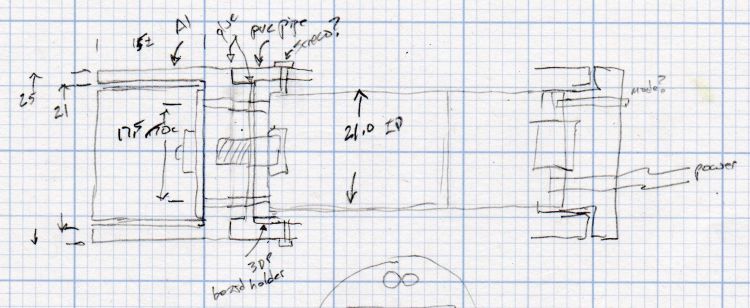

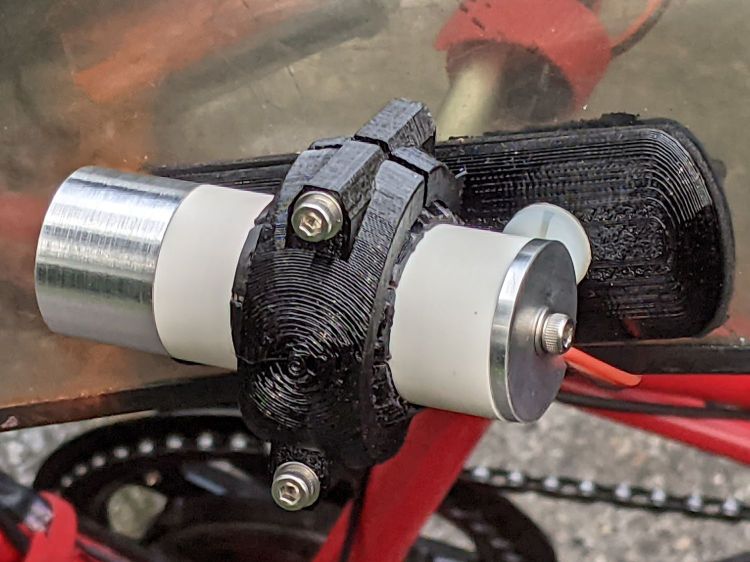

Wrapping a left-side ball mount around the PVC case produced a holder:

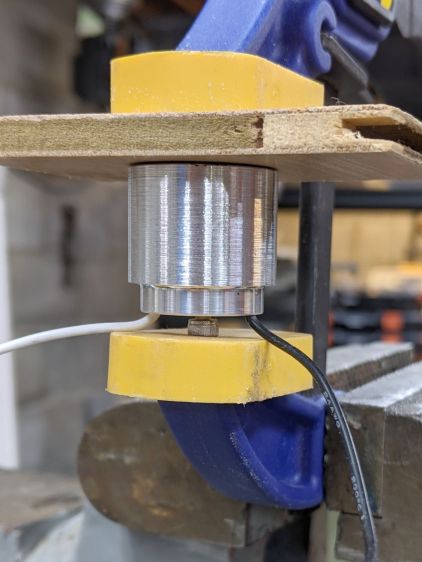

Which looks like this in real life:

The support structure under the arch required a bit more cleanup than it got, so the clamp didn’t quite close around the ball on the first full test:

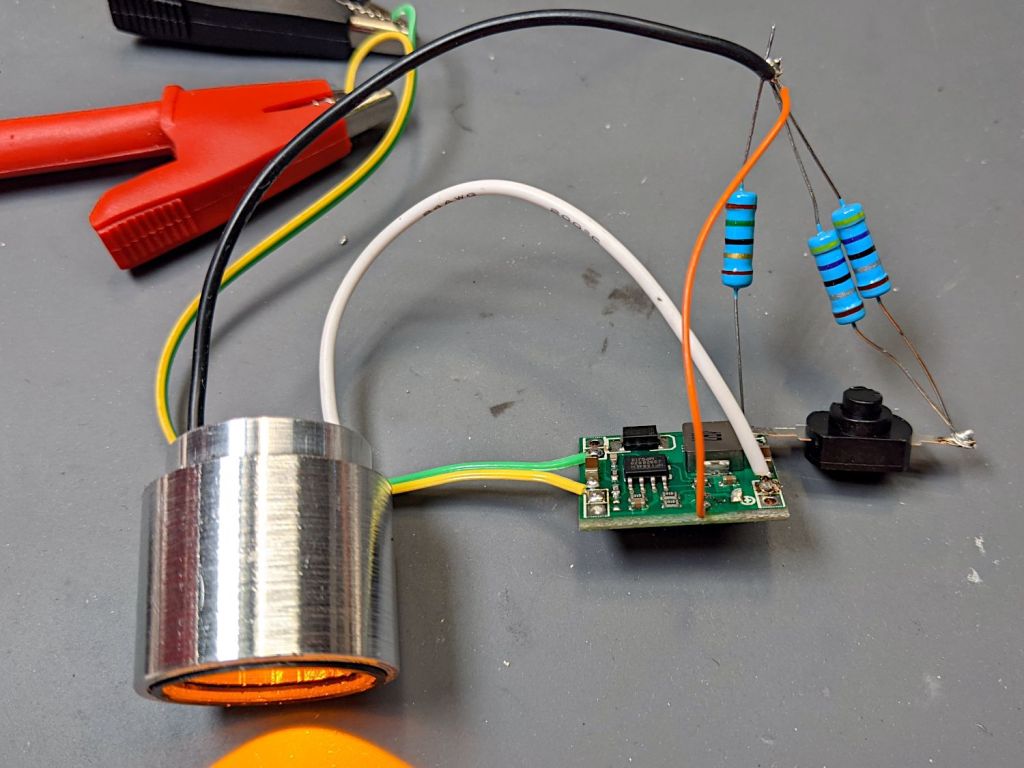

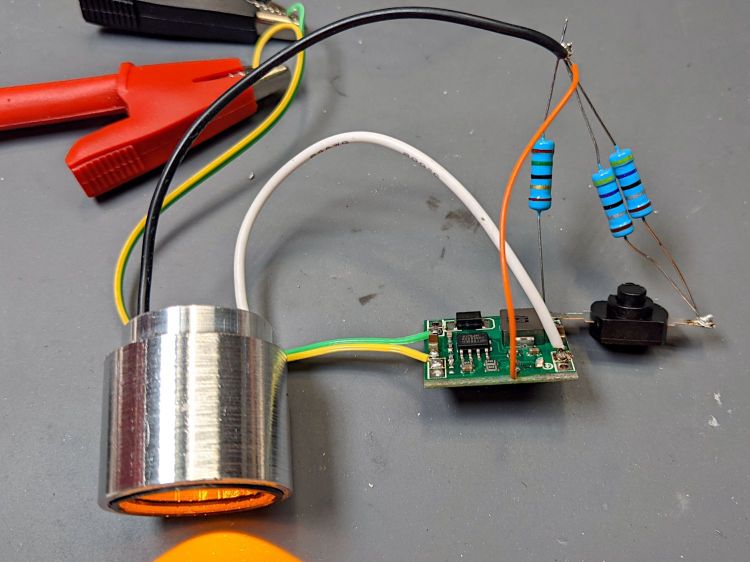

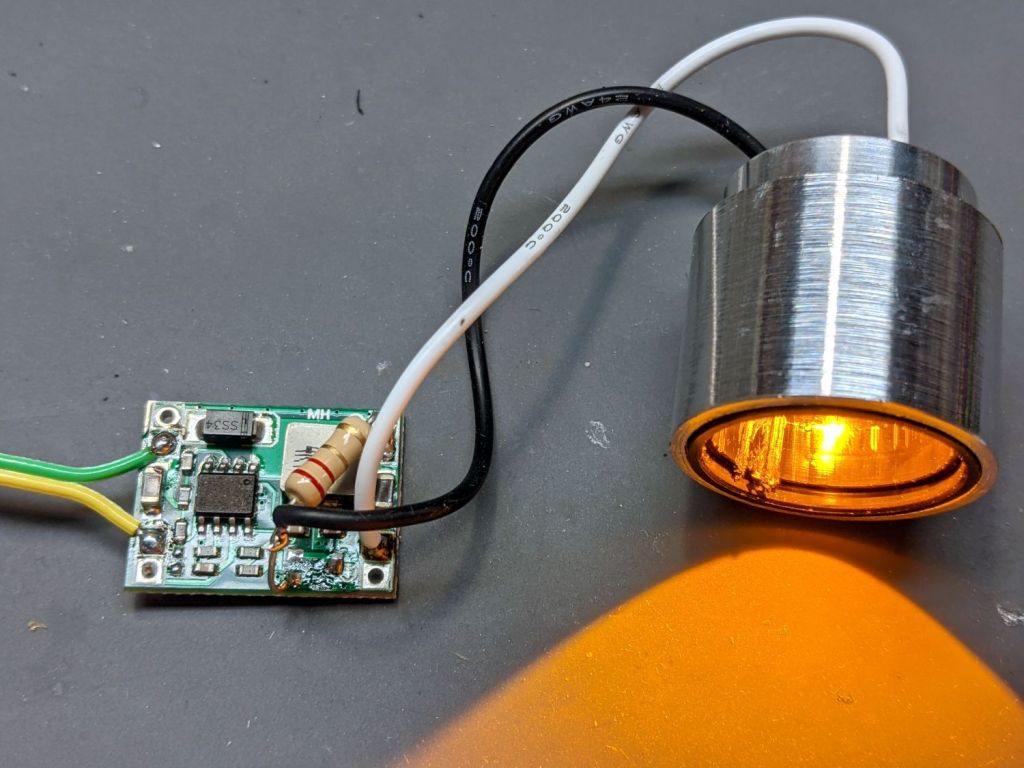

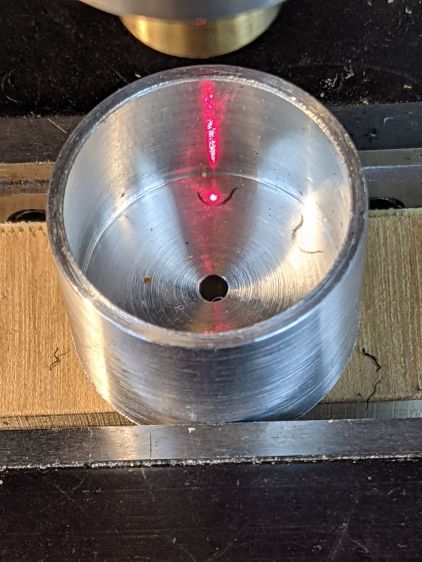

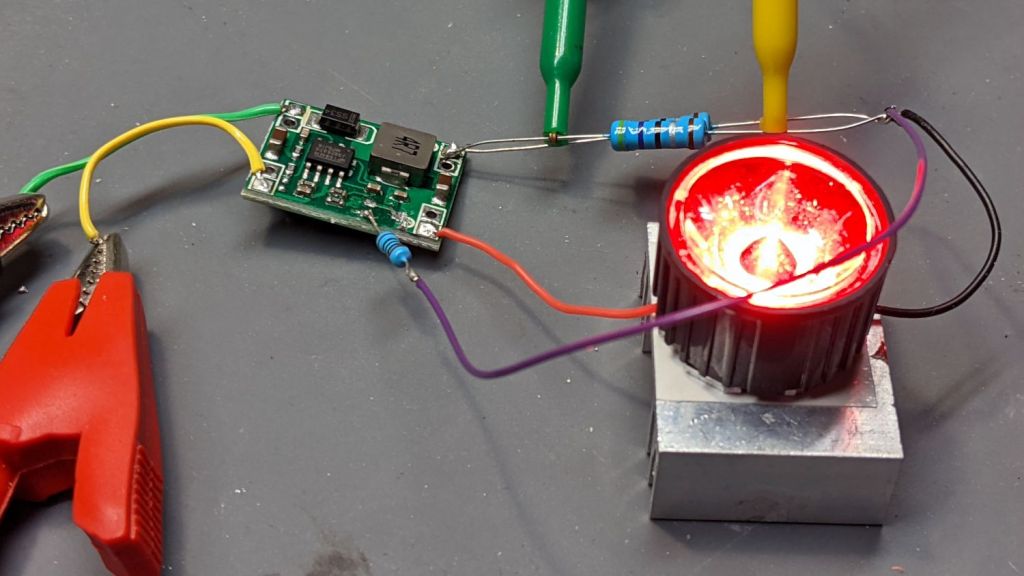

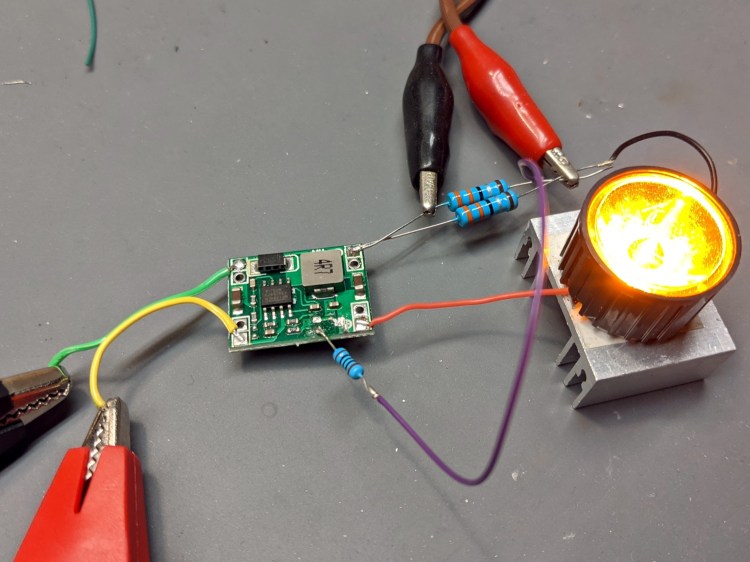

Both the phone camera and the eyeballometer report the 1 W amber LED isn’t quite as bright as the 400 lumen Anker flashlight on its low setting:

Stir the unusual (for a bike) amber color together with some blinkiness, though, and it’s definitely attention-getting.

The OpenSCAD source code as a GitHub Gist:

| // Tour Easy Fairing Flashlight Mount | |

| // Ed Nisley KE4ZNU – July 2017 | |

| // August 2017 – | |

| // August 2020 – add reinforcing columns under mount cradle | |

| // August 2021 – 1 W Amber LED | |

| /* [Build Options] */ | |

| FlashName = "1WLED"; // [AnkerLC40,AnkerLC90,J5TactV2,InnovaX5,Sidemarker,Clearance,Laser,1WLED] | |

| Component = "BallClamp"; // [Ball, BallClamp, Mount, Plates, Bracket, Complete] | |

| Layout = "Build"; // [Build, Show] | |

| Support = true; | |

| MountSupport = true; | |

| /* [Hidden] */ | |

| ThreadThick = 0.25; // [0.20, 0.25] | |

| ThreadWidth = 0.40; // [0.40] | |

| function IntegerMultiple(Size,Unit) = Unit * ceil(Size / Unit); | |

| Protrusion = 0.01; // [0.01, 0.1] | |

| HoleWindage = 0.2; | |

| /* [Fairing Mount] */ | |

| Side = "Right"; // [Right,Left] | |

| ToeIn = -10; // inward from ahead | |

| Tilt = 20; // upward from forward (M=20 E=10) | |

| Roll = 0; // outward from top | |

| //- Screws and inserts | |

| /* [Hidden] */ | |

| ID = 0; | |

| OD = 1; | |

| LENGTH = 2; | |

| /* [Hidden] */ | |

| ClampInsert = [3.0,4.2,8.0]; | |

| ClampScrew = [3.0,5.9,35.0]; // thread dia, head OD, screw length | |

| ClampScrewWasher = [3.0,6.75,0.5]; | |

| ClampScrewNut = [3.0,6.1,4.0]; // nyloc nut | |

| /* [Hidden] */ | |

| F_NAME = 0; | |

| F_GRIPOD = 1; | |

| F_GRIPLEN = 2; | |

| LightBodies = [ | |

| ["AnkerLC90",26.6,48.0], | |

| ["AnkerLC40",26.6,55.0], | |

| ["J5TactV2",25.0,30.0], | |

| ["InnovaX5",22.0,55.0], | |

| ["Sidemarker",15.0,20.0], | |

| ["Clearance",50.0,20.0], | |

| ["Laser",10.0,30.0], | |

| ["1WLED",25.4,40.0], | |

| ]; | |

| //- Fairing Bracket | |

| // Magic numbers taken from the actual fairing mount | |

| /* [Hidden] */ | |

| inch = 25.4; | |

| BracketHoleOD = 0.25 * inch; // 1/4-20 bolt holes | |

| BracketHoleOC = 1.0 * inch; // fairing hole spacing | |

| // usually 1 inch, but 15/16 on one fairing | |

| Bracket = [48.0,16.3,3.6 – 0.6]; // fairing bracket end plate overall size | |

| BracketHoleOffset = (3/8) * inch; // end to hole center | |

| BracketM = 3.0; // endcap arc height | |

| BracketR = (pow(BracketM,2) + pow(Bracket[1],2)/4) / (2*BracketM); // … radius | |

| //- Base plate dimensions | |

| Plate = [100.0,30.0,6*ThreadThick + Bracket[2]]; | |

| PlateRad = Plate[1]/4; | |

| RoundEnds = true; | |

| echo(str("Base plate thick: ",Plate[2])); | |

| //- Select flashlight data from table | |

| echo(str("Flashlight: ",FlashName)); | |

| FlashIndex = search([FlashName],LightBodies,1,0)[F_NAME]; | |

| //- Set ball dimensions | |

| BallWall = 5.0; // max ball wall thickness | |

| echo(str("Ball wall: ",BallWall)); | |

| BallOD = IntegerMultiple(LightBodies[FlashIndex][F_GRIPOD] + 2*BallWall,1.0); | |

| echo(str(" OD: ",BallOD)); | |

| BallLength = IntegerMultiple(min(sqrt(pow(BallOD,2) – pow(LightBodies[FlashIndex][F_GRIPOD],2)) – 2*4*ThreadThick, | |

| LightBodies[FlashIndex][F_GRIPLEN]),1.0); | |

| echo(str(" length: ",BallLength)); | |

| BallSides = 8*4; | |

| //- Set clamp ring dimensions | |

| //ClampOD = 50; | |

| ClampOD = BallOD + 2*5; | |

| echo(str("Clamp OD: ",ClampOD)); | |

| ClampLength = min(20.0,0.75*BallLength); | |

| echo(str(" length: ",ClampLength)); | |

| ClampScrewOC = IntegerMultiple((ClampOD + BallOD)/2,1); | |

| echo(str(" screw OC: ",ClampScrewOC)); | |

| TiltMirror = (Side == "Right") ? [0,0,0] : [0,1,0]; | |

| //- Adjust hole diameter to make the size come out right | |

| module PolyCyl(Dia,Height,ForceSides=0) { // based on nophead's polyholes | |

| Sides = (ForceSides != 0) ? ForceSides : (ceil(Dia) + 2); | |

| FixDia = Dia / cos(180/Sides); | |

| cylinder(r=(FixDia + HoleWindage)/2,h=Height,$fn=Sides); | |

| } | |

| //- Fairing Bracket | |

| // This part of the fairing mount supports the whole flashlight mount | |

| // Centered on screw hole | |

| module Bracket() { | |

| linear_extrude(height=Bracket[2],convexity=2) | |

| difference() { | |

| translate([(Bracket[0]/2 – BracketHoleOffset),0,0]) | |

| offset(delta=ThreadWidth) | |

| intersection() { | |

| square([Bracket[0],Bracket[1]],center=true); | |

| union() { | |

| for (i=[-1,0,1]) // middle circle fills gap | |

| translate([i*(Bracket[0]/2 – BracketR),0]) | |

| circle(r=BracketR); | |

| } | |

| } | |

| circle(d=BracketHoleOD/cos(180/8),$fn=8); // dead center at the origin | |

| } | |

| } | |

| //- General plate shape | |

| // Centered in the middle of the plate | |

| module PlateBlank() { | |

| difference() { | |

| intersection() { | |

| translate([0,0,Plate[2]/2]) // select upper half of spheres | |

| cube(Plate,center=true); | |

| hull() | |

| if (RoundEnds) | |

| for (i=[-1,1]) | |

| translate([i*(Plate[0]/2 – PlateRad),0,0]) | |

| resize([Plate[1]/2,Plate[1],2*Plate[2]]) | |

| sphere(r=PlateRad); // nice round ends! | |

| else | |

| for (i=[-1,1], j=[-1,1]) | |

| translate([i*(Plate[0]/2 – PlateRad),j*(Plate[1]/2 – PlateRad),0]) | |

| resize([2*PlateRad,2*PlateRad,2*Plate[2]]) | |

| sphere(r=PlateRad); // nice round corners! | |

| } | |

| translate([BracketHoleOC,0,-Protrusion]) // punch screw holes | |

| PolyCyl(BracketHoleOD,2*Plate[2],8); | |

| translate([-BracketHoleOC,0,-Protrusion]) | |

| PolyCyl(BracketHoleOD,2*Plate[2],8); | |

| } | |

| } | |

| //- Inner plate | |

| module InnerPlate() { | |

| difference() { | |

| PlateBlank(); | |

| translate([-BracketHoleOC,0,Plate[2] – Bracket[2] + Protrusion]) // punch fairing bracket | |

| Bracket(); | |

| } | |

| } | |

| //- Outer plate | |

| // With optional legend for orientation and parameters | |

| module OuterPlate(Legend = true) { | |

| TextRotate = (Side == "Left") ? 0 : 180; | |

| difference() { | |

| PlateBlank(); | |

| if (Legend) | |

| mirror([0,1,0]) | |

| translate([0,0,-Protrusion]) | |

| linear_extrude(height=3*ThreadThick + Protrusion) { | |

| translate([BracketHoleOC + 15,0,0]) | |

| text(text=">>>",size=5,spacing=1.20,font="Arial",halign="center",valign="center"); | |

| translate([-BracketHoleOC,8,0]) rotate(TextRotate) | |

| text(text=str("Toe ",ToeIn),size=5,spacing=1.20,font="Arial",halign="center",valign="center"); | |

| translate([-BracketHoleOC,-8,0]) rotate(TextRotate) | |

| text(text=str("Tilt ",Tilt),size=5,spacing=1.20,font="Arial",halign="center",valign="center"); | |

| translate([BracketHoleOC,-8,0]) rotate(TextRotate) | |

| text(text=Side,size=5,spacing=1.20,font="Arial",halign="center",valign="center"); | |

| translate([BracketHoleOC,8,0]) rotate(TextRotate) | |

| text(text=str("Roll ",Roll),size=5,spacing=1.20,font="Arial",halign="center",valign="center"); | |

| translate([0,0,0]) | |

| rotate(90) | |

| text(text="KE4ZNU",size=4,spacing=1.20,font="Arial",halign="center",valign="center"); | |

| } | |

| } | |

| } | |

| //- Slotted ball around flashlight | |

| // Print with brim to ensure adhesion! | |

| module SlotBall() { | |

| NumSlots = 8*2; // must be even, half cut from each end | |

| SlotWidth = 2*ThreadWidth; | |

| SlotBaseThick = 10*ThreadThick; // enough to hold finger ends together | |

| RibLength = (BallOD – LightBodies[FlashIndex][F_GRIPOD])/2; | |

| translate([0,0,(Layout == "Build") ? BallLength/2 : 0]) | |

| rotate([0,(Layout == "Show") ? 90 : 0,0]) | |

| difference() { | |

| intersection() { | |

| sphere(d=BallOD,$fn=2*BallSides); // basic ball | |

| cube([2*BallOD,2*BallOD,BallLength],center=true); // trim to length | |

| } | |

| translate([0,0,-LightBodies[FlashIndex][F_GRIPOD]]) | |

| rotate(180/BallSides) | |

| PolyCyl(LightBodies[FlashIndex][F_GRIPOD],2*BallOD,BallSides); // remove flashlight body | |

| for (i=[0:NumSlots/2 – 1]) { // cut slots | |

| a=i*(2*360/NumSlots); | |

| SlotCutterLength = LightBodies[FlashIndex][F_GRIPOD]; | |

| rotate(a) | |

| translate([SlotCutterLength/2,0,SlotBaseThick]) | |

| cube([SlotCutterLength,SlotWidth,BallLength],center=true); | |

| rotate(a + 360/NumSlots) | |

| translate([SlotCutterLength/2,0,-SlotBaseThick]) | |

| cube([SlotCutterLength,SlotWidth,BallLength],center=true); | |

| } | |

| } | |

| color("Yellow") | |

| if (Support && (Layout == "Build")) { | |

| for (i=[0:NumSlots-1]) { | |

| a = i*360/NumSlots; | |

| rotate(a + 180/NumSlots) | |

| translate([(LightBodies[FlashIndex][F_GRIPOD] + RibLength)/2 + ThreadWidth,0,BallLength/(2*4)]) | |

| cube([RibLength,2*ThreadWidth,BallLength/4],center=true); | |

| } | |

| } | |

| } | |

| //- Clamp around flashlight ball | |

| BossLength = ClampScrew[LENGTH] – 1*ClampScrewWasher[LENGTH]; | |

| BossOD = ClampInsert[OD] + 2*(6*ThreadWidth); | |

| module BallClamp(Section="All") { | |

| difference() { | |

| union() { | |

| intersection() { | |

| sphere(d=ClampOD,$fn=BallSides); // exterior ball clamp | |

| cube([ClampLength,2*ClampOD,2*ClampOD],center=true); // aiming allowance | |

| } | |

| hull() | |

| for (j=[-1,1]) | |

| translate([0,j*ClampScrewOC/2,-BossLength/2]) | |

| cylinder(d=BossOD,h=BossLength,$fn=6); | |

| } | |

| sphere(d=(BallOD + 1*ThreadThick),$fn=BallSides); // interior ball with minimal clearance | |

| for (j=[-1,1]) { | |

| translate([0,j*ClampScrewOC/2,-ClampOD]) // screw clearance | |

| PolyCyl(ClampScrew[ID],2*ClampOD,6); | |

| translate([0,j*ClampScrewOC/2, // insert clearance | |

| -0*(BossLength/2 – ClampInsert[LENGTH] – 3*ThreadThick) + Protrusion]) | |

| rotate([0,180,0]) | |

| PolyCyl(ClampInsert[OD],2*ClampOD,6); | |

| translate([0,j*ClampScrewOC/2, // insert transition | |

| -(BossLength/2 – ClampInsert[LENGTH] – 3*ThreadThick)]) | |

| cylinder(d1=ClampInsert[OD]/cos(180/6),d2=ClampScrew[ID],h=6*ThreadThick,$fn=6); | |

| } | |

| if (Section == "Top") | |

| translate([0,0,-ClampOD/2]) | |

| cube([2*ClampOD,2*ClampOD,ClampOD],center=true); | |

| else if (Section == "Bottom") | |

| translate([0,0,ClampOD/2]) | |

| cube([2*ClampOD,2*ClampOD,ClampOD],center=true); | |

| } | |

| color("Yellow") | |

| if (Support) { // ad-hoc supports | |

| NumRibs = 6; | |

| RibLength = 0.5 * BallOD; | |

| RibWidth = 1.9*ThreadWidth; | |

| SupportOC = ClampLength / NumRibs; | |

| if (Section == "Top") // base plate for adhesion | |

| translate([0,0,ThreadThick]) | |

| cube([ClampLength + 6*ThreadWidth,RibLength,2*ThreadThick],center=true); | |

| else if (Section == "Bottom") | |

| translate([0,0,-ThreadThick]) | |

| cube([ClampLength + 6*ThreadWidth,RibLength,2*ThreadThick],center=true); | |

| render(convexity=2*NumRibs) | |

| intersection() { | |

| sphere(d=BallOD – 0*ThreadWidth); // cut at inner sphere OD | |

| cube([ClampLength + 2*ThreadWidth,RibLength,BallOD],center=true); | |

| if (Section == "Top") // select only desired section | |

| translate([0,0,ClampOD/2]) | |

| cube([2*ClampOD,2*ClampOD,ClampOD],center=true); | |

| else if (Section == "Bottom") | |

| translate([0,0,-ClampOD/2]) | |

| cube([2*ClampOD,2*ClampOD,ClampOD],center=true); | |

| union() { // ribs for E-Z build | |

| for (j=[-1,0,1]) | |

| translate([0,j*SupportOC,0]) | |

| cube([ClampLength,RibWidth,1.0*BallOD],center=true); | |

| for (i=[0:NumRibs]) // allow NumRibs + 1 to fill the far end | |

| translate([i*SupportOC – ClampLength/2,0,0]) | |

| rotate([0,90,0]) | |

| cylinder(d=BallOD – 2*ThreadThick, | |

| h=RibWidth,$fn=BallSides,center=true); | |

| } | |

| } | |

| } | |

| } | |

| //- Mount between fairing plate and flashlight ball | |

| // Build with support for bottom of clamp screws! | |

| module Mount() { | |

| MountShift = [ClampOD*sin(ToeIn/2),0,ClampOD/2]; | |

| OuterPlate(); | |

| mirror(TiltMirror) { | |

| intersection() { | |

| translate(MountShift) | |

| rotate([-Roll,ToeIn,Tilt]) | |

| BallClamp("Bottom"); | |

| translate([0,0,Plate.x/2 + 3*ThreadThick]) | |

| cube(Plate.x,center=true); | |

| } | |

| if (MountSupport) // anchor outer corners at worst overhang | |

| color("Yellow") { | |

| RibWidth = 1.9*ThreadWidth; | |

| SupportOC = 0.1 * ClampLength; | |

| intersection() { | |

| difference() { | |

| rotate([0,0,Tilt]) | |

| translate([(ClampOD – BallOD)*sin(ToeIn/2),0,3*ThreadThick]) // Z = avoid legends | |

| for (i=[-4.5,-2.5,0,2.0,4.5]) | |

| translate([i*SupportOC – 0.0,0,(5 + Plate[2])/2]) | |

| cube([RibWidth,0.7*ClampOD,(5 + Plate[2])],center=true); | |

| translate(MountShift) | |

| rotate([-Roll,ToeIn,Tilt]) | |

| sphere(d=ClampOD – 2*ThreadWidth,$fn=BallSides); | |

| } | |

| translate([0,0,ClampOD/2]) | |

| cube([Plate.x,Plate.y,ClampOD],center=true); | |

| } | |

| } | |

| } | |

| } | |

| //- Build things | |

| if (Component == "Bracket") | |

| Bracket(); | |

| if (Component == "Ball") | |

| SlotBall(); | |

| if (Component == "BallClamp") | |

| if (Layout == "Show") | |

| BallClamp("All"); | |

| else if (Layout == "Build") | |

| BallClamp("Top"); | |

| if (Component == "Mount") | |

| Mount(); | |

| if (Component == "Plates") { | |

| translate([0,0.7*Plate[1],0]) | |

| InnerPlate(); | |

| translate([0,-0.7*Plate[1],0]) | |

| OuterPlate(Legend = false); | |

| } | |

| if (Component == "Complete") { | |

| OuterPlate(); | |

| mirror(TiltMirror) { | |

| translate([0,0,ClampOD/2 + BossOD*abs(sin(ToeIn))]) { | |

| rotate([-Roll,ToeIn,Tilt]) | |

| SlotBall(); | |

| rotate([-Roll,ToeIn,Tilt]) | |

| BallClamp(); | |

| } | |

| } | |

| } |