I recently engaged in a wide-ranging email exchange with a guy planning to scratch-build a large-format 3D printer. He figured it would be a straightforward exercise and asked for some advice; I may be more cynical that he expected.

Over the next few days, I’ll dump my side of the conversation so I can refer to it in other contexts. I’ve left his side of the conversation as the short quotes that prompted my replies, but you can probably infer what he was thinking.

He’s well-acquainted with CNC machining and recently added a Makergear M2 to his collection …

I’m hooked.

All of sudden, you realize what you’ve been missing!

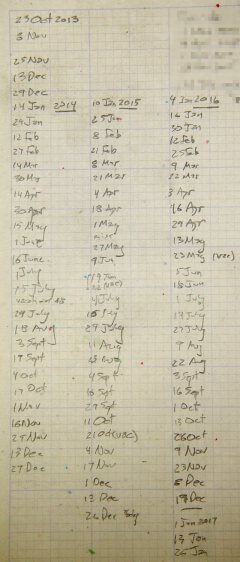

In round numbers, I’ve been designing & printing one “thing” every week for the last five years. Granted, my “things” look a lot like brackets, because they go into other shop projects, but 3D printing is how I make nearly all the shapes I formerly bashed from metal.

I loves me my 3D printer!

an open source design with AFFORDABLE, EASILY ACCESSIBLE parts with a build platform of at least 150% X/Y volume of the MakerGear

Some years ago, I had the same general idea. Then I bought an M2 (replacing my Thing-O-Matic), considered LinuxCNC / Machinekit for motion control, and realized there wasn’t much point; I didn’t want to devote far too much time & effort to solving an already solved problem.

A larger build volume doesn’t buy you as much as you think, while imposing far too many hard constraints. Basically, good-resolution extruders run at 2 to 10 mm³/s, so large objects require print times beyond the 12-hour MTTF of the “printing system”: something will go wrong often enough to drive you mad.

Bonus: plastic’s thermal coefficient guarantees bed adhesion problems. Using high-traction materials (PEI / hairspray / whatever) introduces problems in the other direction. There’s a limit to how big you can make things before they either don’t stick or stick too hard.

Some the fundamental design problems that nobody recognizes until far too late in their design:

- nozzle-to-platform accuracy < ±0.05 mm

- XY axis speeds 30 mm/s to 500 mm/s

- Z axis stiction & backlash < 0.1 mm

- filament drive with excellent retraction control / speed

- bed adhesion vs. part removal vs. Z accuracy

- Arduino-class firmware (Marlin, et. al.) is a dead end

- Windows is crap in any part of a machine-control problem

Those are hard requirements. At a minimum, your design must satisfy all of them: miss any one and you’re not in the game. It’s easy to build a cheap and crappy fused-filament 3D printer (see Kickstarter), but exceedingly difficult to build one at the state of the art (see patent litigation).

The M2 descends from the original RepRap design, with the Y axis slinging far too much mass back & forth. That kills nozzle-to-platform accuracy, introduces temperature instability, and soaks up bench space. On the other paw, look at the problems Makerbot (not Makergear) had with their direct-drive extruder on an XY platform; getting that right requires nontrivial engineering

Bowden filament drives have improved, but really can’t provide enough retraction control / speed. Delta printers always use Bowden drives, because they can’t sling a direct-drive extruder with enough XYZ speed & accuracy. Bowden on an XY platform has the worst of both worlds: bad retraction and difficult mechanical design.

I think the M2 occupies a sweet spot in 3D printer design: excellent results without excessive complexity or expense. It’s not perfect, but good enough.

But, then, I’m a known curmudgeon …

(Continues tomorrow)