The original ball around the flashlight consisted of two identical parts joined with 2 mm screws and brass inserts:

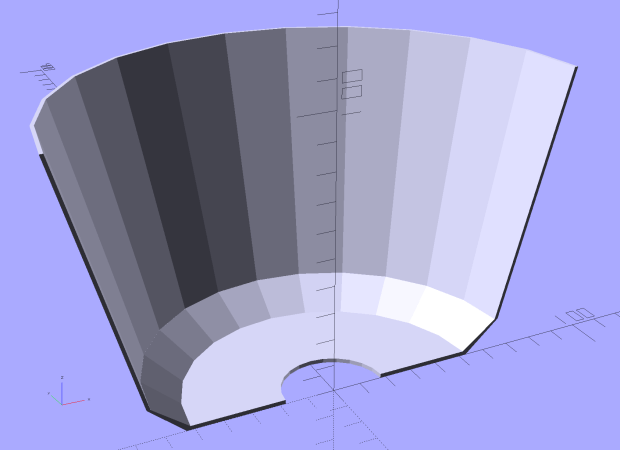

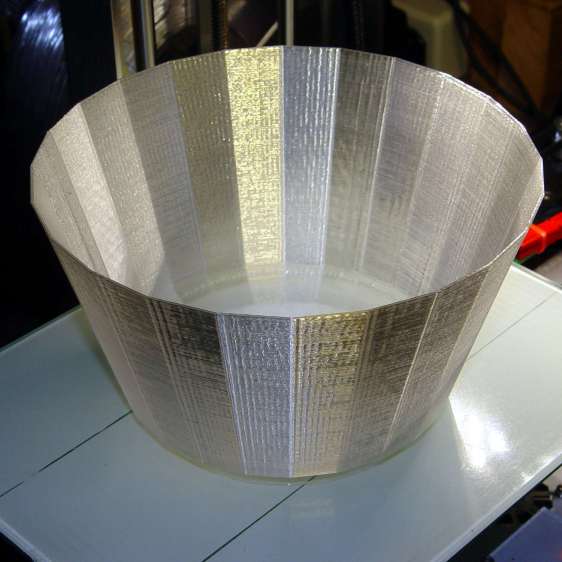

Providing enough space for the inserts made the ball bigger than it really ought be, so I designed a one-piece ball with “expansion joints” between the fingers:

Having Slic3r put a 3 mm brim around the bottom almost worked. Adding a little support flange, then building with a brim, kept each segment upright and the whole affair firmly anchored.

Those had to be part of the model, because I also wanted to anchor the perimeter threads to prevent upward warping. Worked great and cleanup was surprisingly easy: apply the flush cutter, introduce the ball to Mr Belt Sander, then rotate the ball around the flashlight wrapped with fine sandpaper to wear off the nubs.

The joints between the fingers provide enough flexibility to expand slightly around the flashlight body:

I made that one the same size as the original screw + insert balls to fit the original clamp, where it worked fine. The clamp ring applies enough pressure to the ball to secure the flashlight and prevent the ball from rotating unless you (well, I) apply more-than-incidental force.

Then I shrank the ball to the flashlight diameter + 10 mm (= 5 mm thick at the equator) and reduced the size of the clamp ring accordingly, which made the whole mount much more compact:

Here’s what the larger mount looks like in action:

The flashlights allegedly puts out 400 lumen in a fairly tight beam. The fairings produce a much larger and brighter glint in full sunlight than the flashlights, so I think they’re about the right brightness.

The OpenSCAD source code for the new ball as a GitHub Gist:

| //- Slotted ball around flashlight | |

| // Print with brim to ensure adhesion! | |

| module SlotBall() { | |

| NumSlots = 8*2; // must be even, half cut from each end | |

| SlotWidth = 2*ThreadWidth; | |

| SlotBaseThick = 10*ThreadThick; // enough to hold finger ends together | |

| RibLength = (BallOD – LightBodies[FlashIndex][F_GRIPOD])/2; | |

| translate([0,0,BallLength/2]) | |

| difference() { | |

| intersection() { | |

| sphere(d=BallOD,$fn=2*BallSides); // basic ball | |

| cube([2*BallOD,2*BallOD,BallLength],center=true); // trim to length | |

| } | |

| translate([0,0,-LightBodies[FlashIndex][F_GRIPOD]]) | |

| rotate(180/BallSides) | |

| PolyCyl(LightBodies[FlashIndex][F_GRIPOD],2*BallOD,BallSides); // remove flashlight body | |

| for (i=[0:NumSlots/2 – 1]) { // cut slots | |

| a=i*(2*360/NumSlots); | |

| SlotCutterLength = LightBodies[FlashIndex][F_GRIPOD]; | |

| rotate(a) | |

| translate([SlotCutterLength/2,0,SlotBaseThick]) | |

| cube([SlotCutterLength,SlotWidth,BallLength],center=true); | |

| rotate(a + 360/NumSlots) | |

| translate([SlotCutterLength/2,0,-SlotBaseThick]) | |

| cube([SlotCutterLength,SlotWidth,BallLength],center=true); | |

| } | |

| } | |

| color("Yellow") | |

| if (Support) { | |

| for (i=[0:NumSlots-1]) { | |

| a = i*360/NumSlots; | |

| rotate(a + 180/NumSlots) | |

| translate([(LightBodies[FlashIndex][F_GRIPOD] + RibLength)/2 + ThreadWidth,0,BallLength/(2*4)]) | |

| cube([RibLength,2*ThreadWidth,BallLength/4],center=true); | |

| } | |

| } | |

| } |