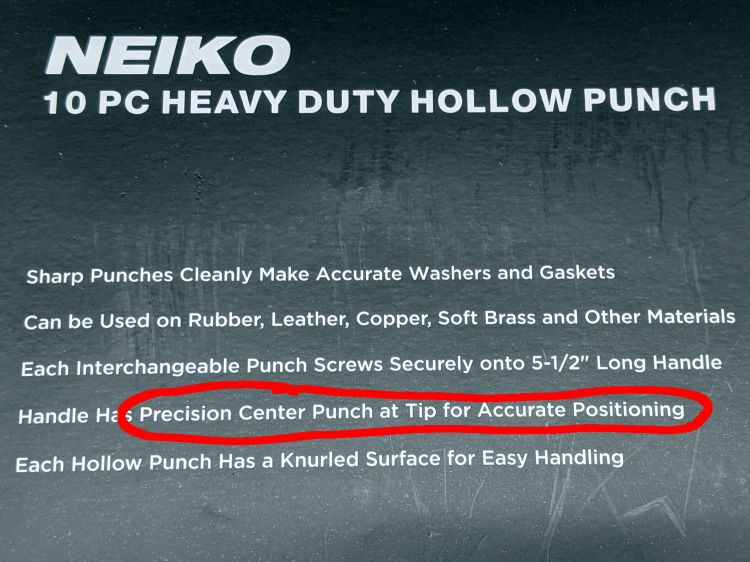

Having struggled to cut nice rings from gooey foam adhesive tape, I got a Neiko hollow hole punch set, despite reviews suggesting the pilot point might be a bit off. The case wrapper claims otherwise:

As the saying (almost) goes:

“

Inconcievable!Precision!”“You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.”

Goldman, The Princess Bride

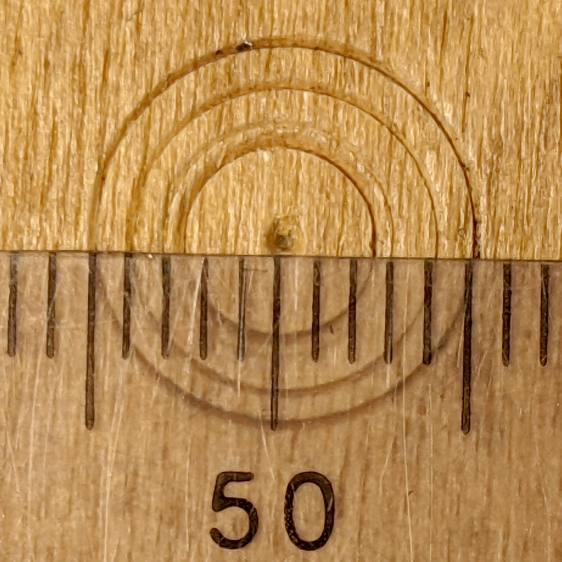

An eyeballometric measurement suggests this is another one of those Chinese tools missing the last 10% of its manufacturing process:

That’s the 5 mm punch, where being (at least) half a millimeter off-center matters more than it would in the 32 mm punch.

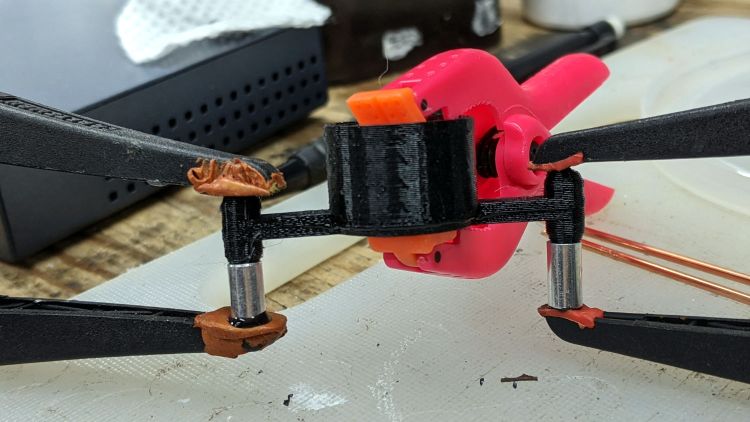

Unscrewing the painfully awkward screw in the side releases the pilot:

The debris on the back end of the pilot is a harbinger of things to come:

Looks like whoever was on spring-cutting duty nicked the next coil with the cutoff wheel. I have no idea where the steel curl came from, as it arrived loose inside the spring.

Although it doesn’t appear here, I replaced that huge screw with a nice stainless steel grub screw that doesn’t stick out at all.

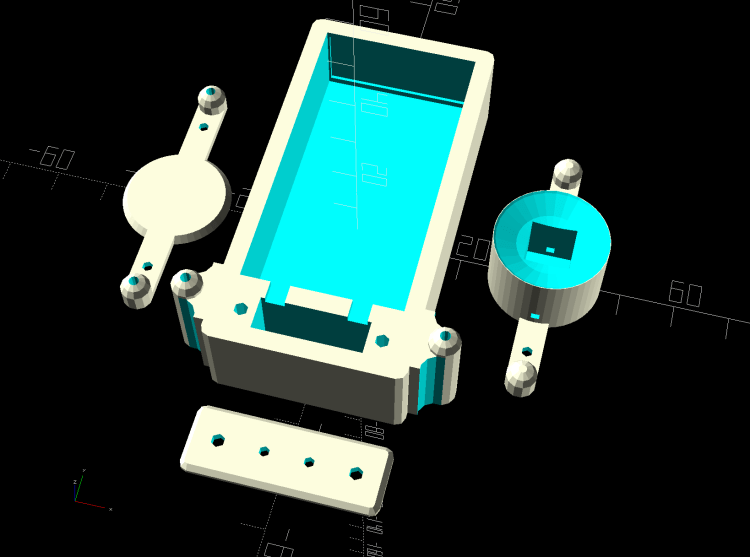

Chucking the pilot in the lathe suggested it was horribly out of true, but cleaning the burrs off the outside diameter and chamfering the edges with a file improved it mightily. Filing doesn’t remove much material, so apparently the pilot is supposed to have half a millimeter of free play in the handle:

That’s looking down at the handle, without a punch screwed onto the threads surrounding the pilot.

Wrapping a rectangle of 2 mil brass shimstock into a cylinder around the pilot removed the slop:

But chucking the handle in the lathe showed the pilot was still grossly off-center, so I set it up for boring:

The entry of the hole was comfortingly on-axis, but the far end was way off-center. I would expect it to be drilled on a lathe and, with a hole that size, it ought to go right down the middle. I’ve drilled a few drunken holes, though.

Truing the hole enlarged it enough to require a 0.5 mm shimstock wrap, but the pilot is now pretty much dead on:

Those are 5, 6, 8, and 10 mm punches whacked into a plywood scrap; looks well under a quarter millimeter to me and plenty good enough for what I need.