After Bill Wittig pointed me in the right direction, writing a Python program to correctly read a rotary encoder knob on a Raspberry Pi is straightforward. At least given some hints revealed by knowing the proper keywords.

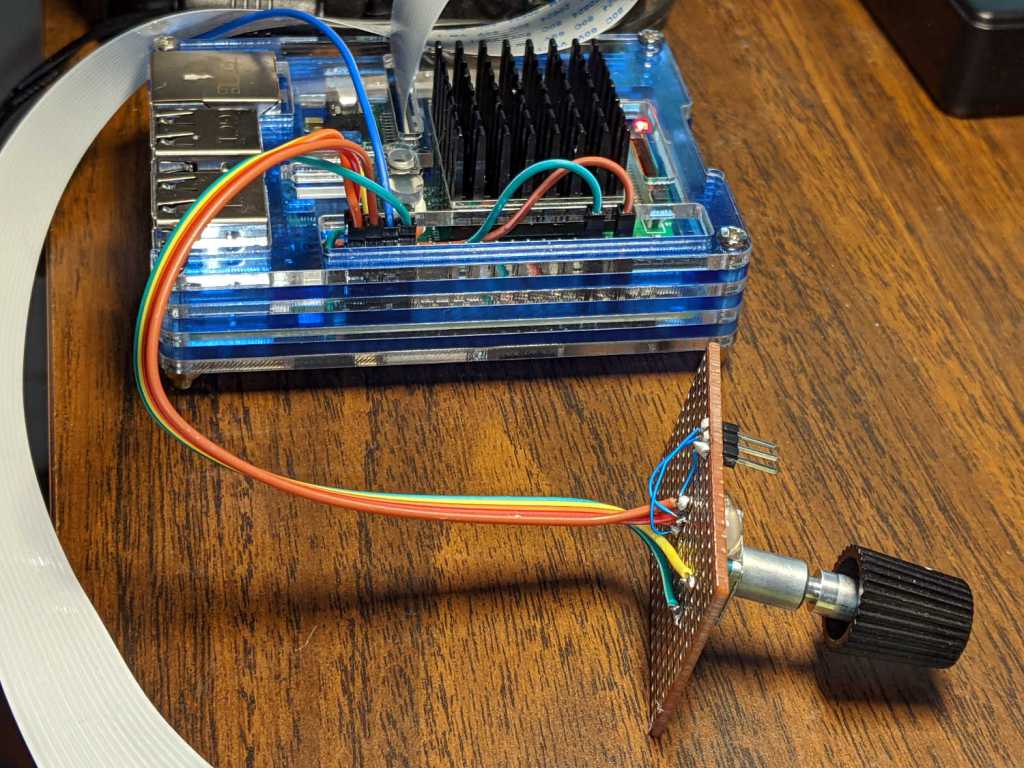

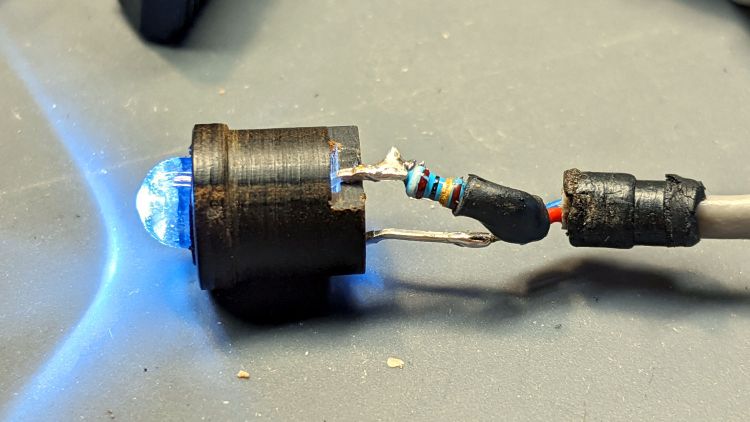

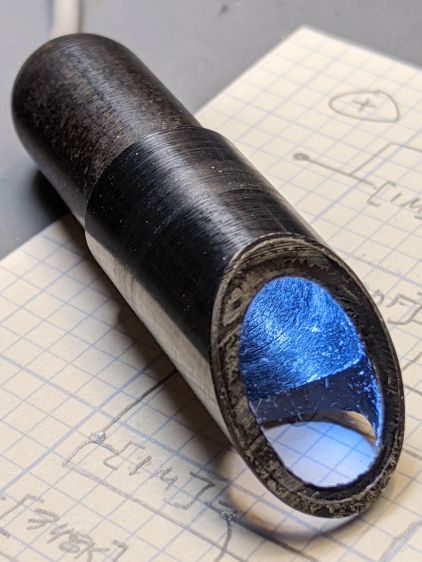

First, enhance the knob’s survivability & usability by sticking it on a perfboard scrap:

Then find the doc in /boot/overlays/README:

Name: rotary-encoder

Info: Overlay for GPIO connected rotary encoder.

Load: dtoverlay=rotary-encoder,

=

Params: pin_a GPIO connected to rotary encoder channel A

(default 4).

pin_b GPIO connected to rotary encoder channel B

(default 17).

relative_axis register a relative axis rather than an

absolute one. Relative axis will only

generate +1/-1 events on the input device,

hence no steps need to be passed.

linux_axis the input subsystem axis to map to this

rotary encoder. Defaults to 0 (ABS_X / REL_X)

rollover Automatic rollover when the rotary value

becomes greater than the specified steps or

smaller than 0. For absolute axis only.

steps-per-period Number of steps (stable states) per period.

The values have the following meaning:

1: Full-period mode (default)

2: Half-period mode

4: Quarter-period mode

steps Number of steps in a full turnaround of the

encoder. Only relevant for absolute axis.

Defaults to 24 which is a typical value for

such devices.

wakeup Boolean, rotary encoder can wake up the

system.

encoding String, the method used to encode steps.

Supported are "gray" (the default and more

common) and "binary".Add a line to /boot/config.txt to configure the hardware:

dtoverlay=rotary-encoder,pin_a=20,pin_b=21,relative_axis=1,steps-per-period=2The overlay enables the pullup resistors by default, so the encoder just pulls the pins to common. Swapping the pins reverses the sign of the increments, which may be easier than swapping the connector after you have it all wired up.

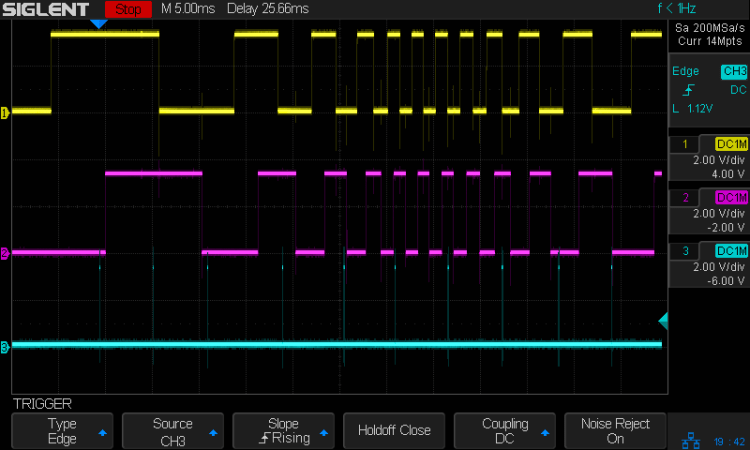

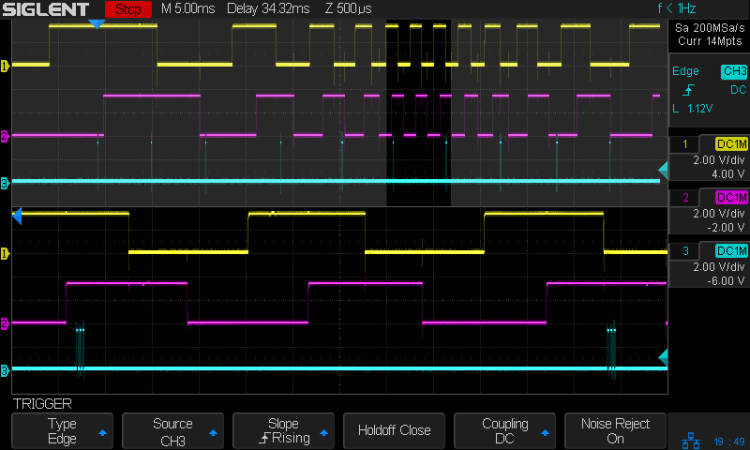

The steps-per-period matches the encoder in hand, which has 30 detents per full turn; the default value of 1 step/period resulted in every other detent doing nothing. A relative axis produces increments of +1 and -1, rather than the accumulated value useful for an absolute encoder with hard physical stops.

Reboot that sucker and an event device pops up:

ll /dev/input

total 0

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 80 Oct 18 07:46 by-path

crw-rw---- 1 root input 13, 64 Oct 18 07:46 event0

crw-rw---- 1 root input 13, 65 Oct 18 07:46 event1

crw-rw---- 1 root input 13, 63 Oct 18 07:46 mice

I’m unable to find the udev rule (or whatever) creating those aliases and, as with all udev trickery, the device’s numeric suffix is not deterministic. The only way you (well, I) can tell which device is the encoder and which is the power-off button is through their aliases:

ll /dev/input/by-path/

total 0

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 9 Oct 18 07:46 platform-rotary@14-event -> ../event0

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 9 Oct 18 07:46 platform-soc:shutdown_button-event -> ../event1

The X axis of the mice device might report the same values, but calling a rotary encoder a mouse seems fraught with technical debt.

The name uses the hex equivalent of the A channel pin number (20 = 0x14), so swapping the pins in the configuration will change the device name; rewiring the connector may be easier.

Using the alias means you always get the correct device:

# Rotary encoder using evdev

# Add to /boot/config.txt

# dtoverlay=rotary-encoder,pin_a=20,pin_b=21,relative_axis=1,steps-per-period=2

# Tweak pins and steps to match the encoder

import evdev

d = evdev.InputDevice('/dev/input/by-path/platform-rotary@14-event')

print('Rotary encoder device: {}'.format(d.name))

position = 0

for e in d.read_loop():

print('Event: {}'.format(e))

if e.type == evdev.ecodes.EV_REL:

position += e.value

print('Position: {}'.format(position))

Which should produce output along these lines:

Rotary encoder device: rotary@14

Event: event at 1603019654.750255, code 00, type 02, val 01

Position: 1

Event: event at 1603019654.750255, code 00, type 00, val 00

Event: event at 1603019654.806492, code 00, type 02, val 01

Position: 2

Event: event at 1603019654.806492, code 00, type 00, val 00

Event: event at 1603019654.949199, code 00, type 02, val 01

Position: 3

Event: event at 1603019654.949199, code 00, type 00, val 00

Event: event at 1603019655.423506, code 00, type 02, val -1

Position: 2

Event: event at 1603019655.423506, code 00, type 00, val 00

Event: event at 1603019655.493140, code 00, type 02, val -1

Position: 1

Event: event at 1603019655.493140, code 00, type 00, val 00

Event: event at 1603019655.624685, code 00, type 02, val -1

Position: 0

Event: event at 1603019655.624685, code 00, type 00, val 00

Event: event at 1603019657.652883, code 00, type 02, val -1

Position: -1

Event: event at 1603019657.652883, code 00, type 00, val 00

Event: event at 1603019657.718956, code 00, type 02, val -1

Position: -2

Event: event at 1603019657.718956, code 00, type 00, val 00

Event: event at 1603019657.880569, code 00, type 02, val -1

Position: -3

Event: event at 1603019657.880569, code 00, type 00, val 00

The type 00 events are synchronization points, which might be more useful with more complex devices.

Because the events happen outside the kernel scheduler’s notice, you (well, I) can now spin the knob as fast as possible and the machinery will generate one increment per transition, so the accumulated position changes smoothly.

Much better!