|

// Bird feeder tray mount |

|

// Ed Nisley – KE4ZNU |

|

// 2025-11-06 |

|

|

|

include <BOSL2/std.scad> |

|

|

|

Layout = "Show"; // [Build,Show,Lid,Mount,Segment,Nut] |

|

|

|

/* [Hidden] */ |

|

|

|

ID = 0; |

|

OD = 1; |

|

LENGTH = 2; |

|

|

|

HoleWindage = [0.2,0.2,0.2]; |

|

Protrusion = 0.1; |

|

|

|

NumRibs = 12; // stiffening ribs |

|

NumSides = 8*NumRibs; |

|

|

|

$fn=NumSides; |

|

|

|

Gap = 5.0; |

|

|

|

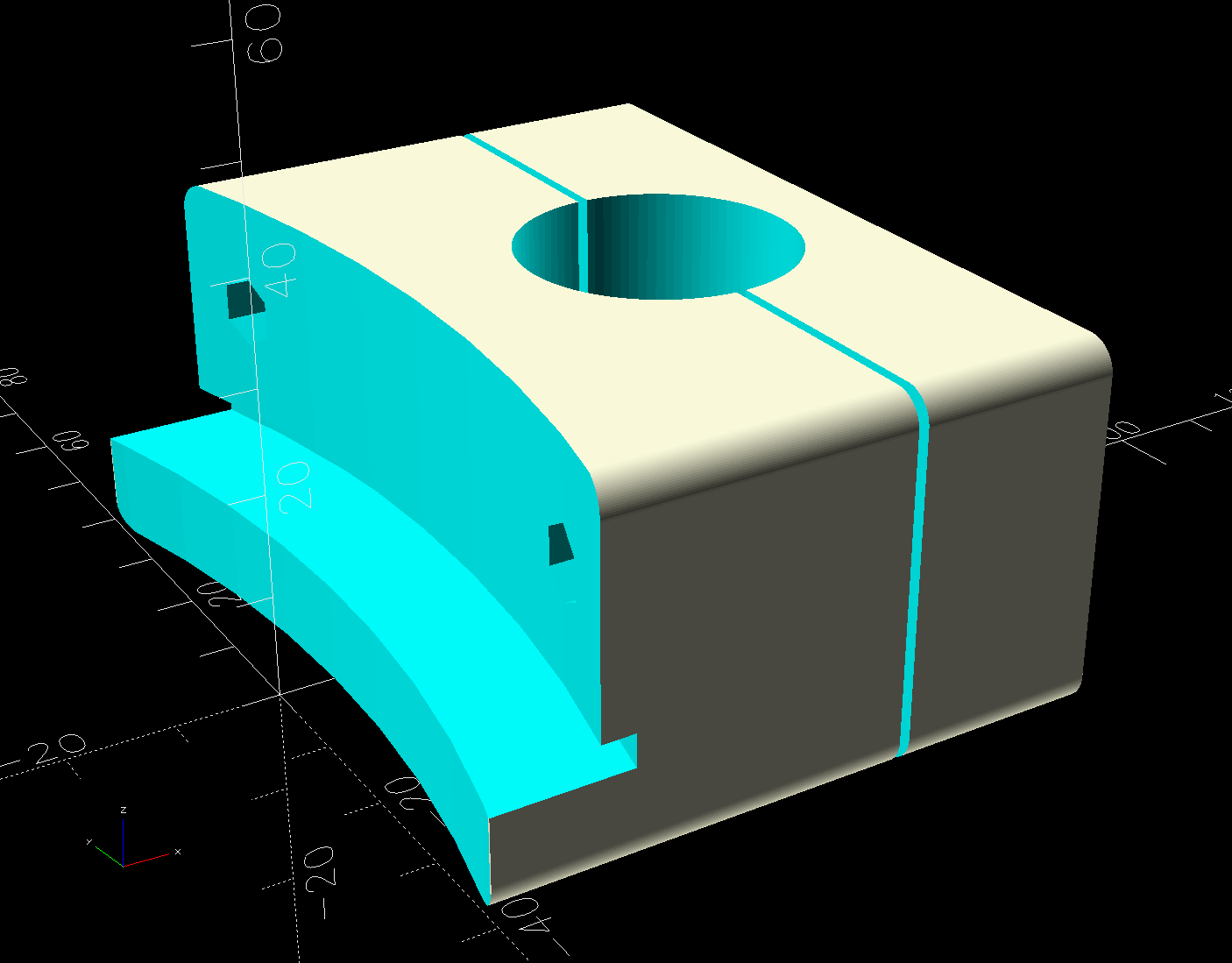

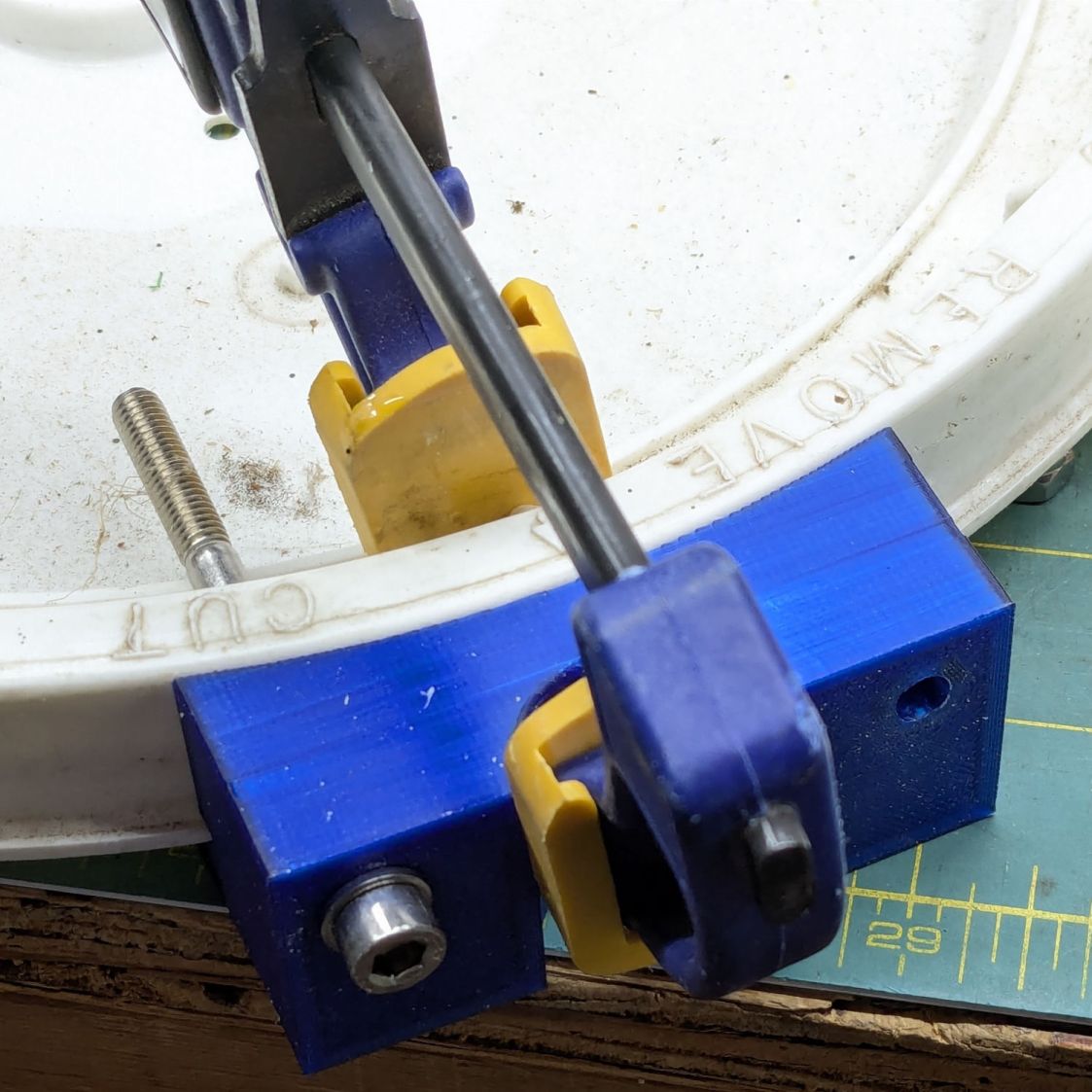

WallThick = 9.0; // robust walls |

|

Kerf = 1.0; // clamp cut |

|

TapeThick = 0.5; // wrap around pole |

|

|

|

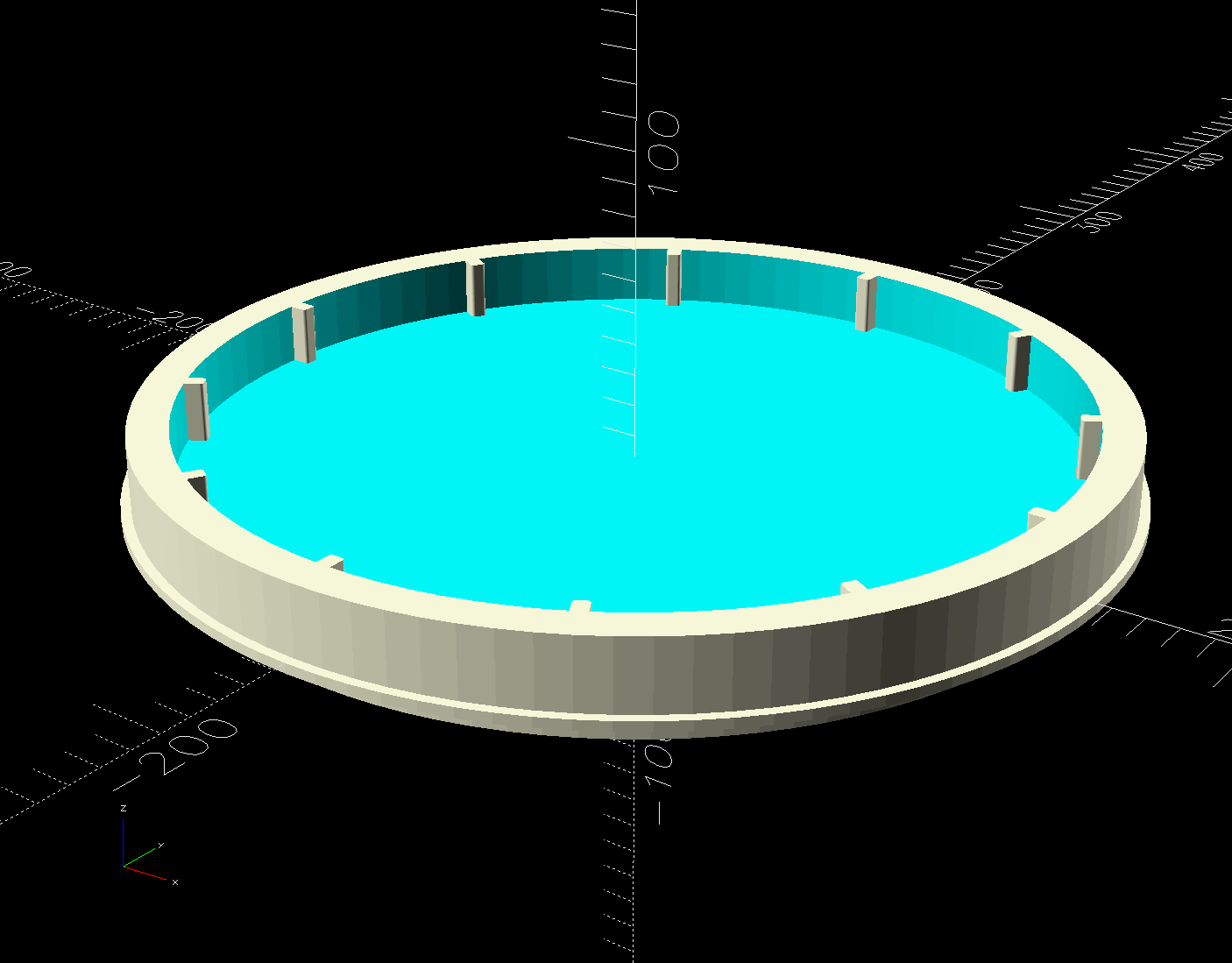

LidOD = 12; // main diameter in inches |

|

|

|

PoleOD = 1*INCH; |

|

|

|

PlateThick = 2.0; // backing plate for clamp |

|

|

|

Screw = [6.0,12.0,6.0]; // thread OD, washerOD, head |

|

ScrewLength = 75.0; |

|

|

|

ScrewOC = 60.0; // chosen to clear stiffening ribs in lid |

|

|

|

LidLayers = [ // bottom to top, ID = 0 means solid disk, LENGTH = exterior measurement |

|

[0,(LidOD-2*(3/8))*INCH,Protrusion], // 0 – below zero to prevent Z fighting |

|

[0,(LidOD-2*(3/8))*INCH,(3/8)*INCH], // 1 – base inside bucket |

|

[0,(LidOD+2*(1/8))*INCH,(1/8)*INCH], // 2 – flange |

|

[(LidOD-2*(1/2))*INCH,LidOD*INCH,(7/8)*INCH], // 3 – sealing ring |

|

]; |

|

|

|

LidOAH = LidLayers[1][LENGTH] + LidLayers[2][LENGTH] + LidLayers[3][LENGTH]; |

|

LidTopDepth = (3/4)*INCH; // from highest part of interior |

|

|

|

MountBlockWidth = ScrewOC + 2*WallThick; |

|

|

|

BaseSagitta = LidLayers[1][OD]/2 – sqrt((LidLayers[1][OD]/2)^2 – (MountBlockWidth^2)/4); |

|

echo(BaseSagitta=BaseSagitta); |

|

|

|

PoleOffset = BaseSagitta + ((LidLayers[2][OD] – LidLayers[1][OD])/2) + WallThick + PoleOD/2; |

|

|

|

MountBlock = [PoleOffset + PoleOD/2 + WallThick – PlateThick,MountBlockWidth,LidOAH]; |

|

echo(MountBlock=MountBlock); |

|

|

|

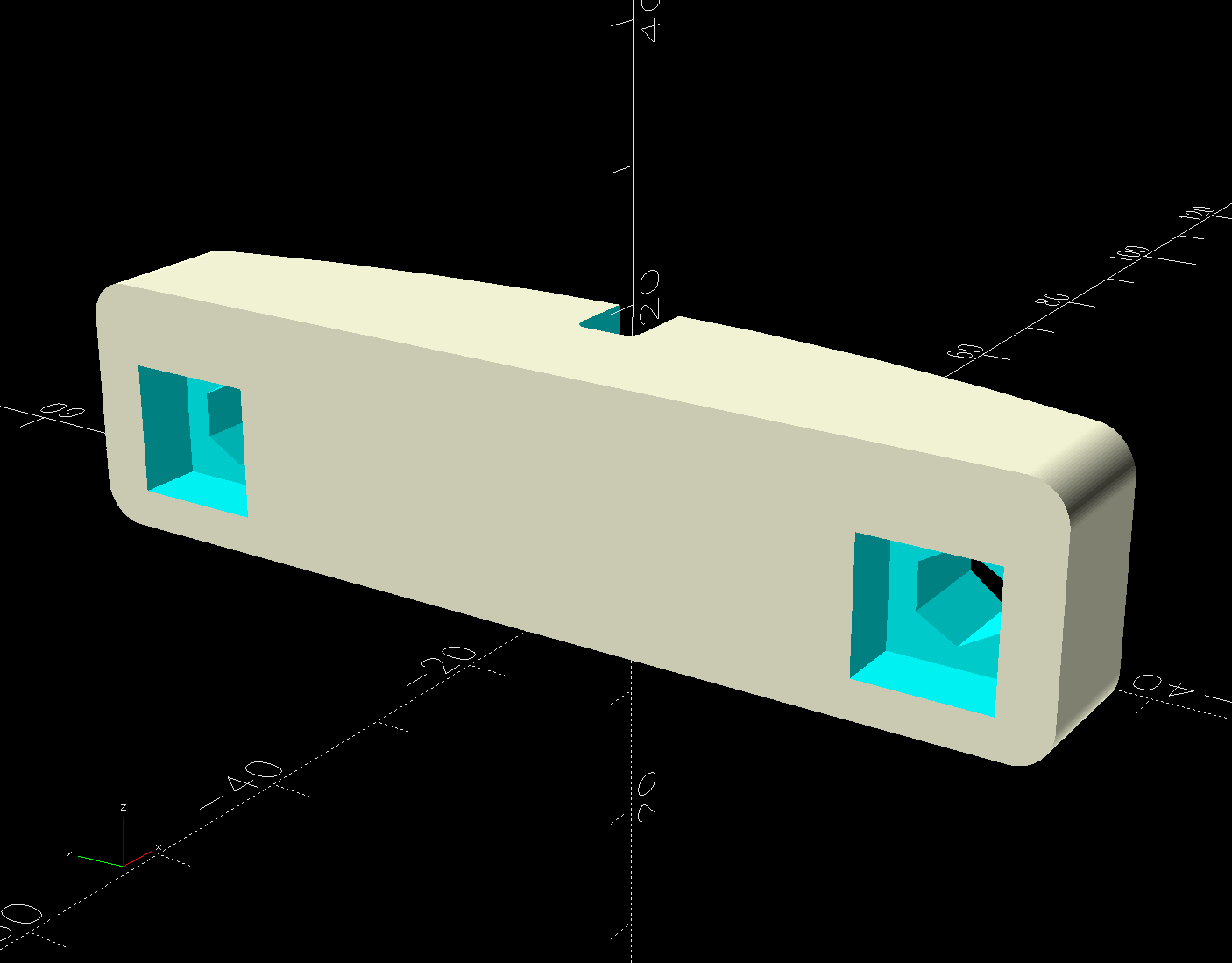

SegBlockOffset = ScrewLength – MountBlock.x – PlateThick; // assumes recessed |

|

SegmentBlock = [2*SegBlockOffset,MountBlock.y,LidTopDepth]; |

|

|

|

Rib = [2*6.0,5.0,LidTopDepth]; // lid stiffening ribs |

|

RibAlign = 0 * 180/NumRibs; // position ribs wrt mount |

|

|

|

EdgeRadius = 3.0; |

|

|

|

//—– |

|

// Rivnut |

|

// The model collects all the magic numbers right here |

|

|

|

/* |

|

RivnutOAL = 15.0; |

|

|

|

module Rivnut() { |

|

|

|

union() { |

|

cyl(1.6,d=13.0,circum=true,anchor=BOTTOM); |

|

cyl(RivnutOAL,d=9.0,circum=true,anchor=BOTTOM); |

|

} |

|

|

|

} |

|

|

|

*/ |

|

|

|

//—– |

|

// Square nut |

|

// The model collects all the magic numbers right here |

|

|

|

NutOAL = 5.0; |

|

|

|

module SquareNut() { |

|

|

|

cuboid([10.0,10.0,5.0],anchor=BOTTOM); |

|

|

|

} |

|

//—– |

|

// Bucket lid |

|

// Centered at XY=0, Z=0 at top of exterior flange |

|

|

|

module BucketLid(Interior=true,Expand=false) { |

|

|

|

render() |

|

union() { |

|

down(LidLayers[2][LENGTH]) |

|

cyl(LidLayers[1][LENGTH],d=LidLayers[1][OD],anchor=TOP); |

|

cyl(LidLayers[2][LENGTH],d=LidLayers[2][OD],anchor=TOP); |

|

if (Interior) { |

|

if (false) |

|

down(Expand ? Protrusion : 0) |

|

tube(LidLayers[3][LENGTH] + (Expand ? 2*Protrusion : 0), |

|

id=LidLayers[3][ID],od=(Expand ? 2 : 1)*LidLayers[3][OD],anchor=BOTTOM); |

|

else |

|

difference() { |

|

cyl(LidLayers[3][LENGTH] + (Expand ? 2*Protrusion : 0), |

|

d=(Expand ? 2 : 1)*LidLayers[3][OD],anchor=BOTTOM); |

|

up(LidLayers[3][LENGTH] – LidTopDepth) |

|

cyl(LidTopDepth + (Expand ? 2*Protrusion : 0), |

|

d=LidLayers[3][ID],anchor=BOTTOM); |

|

} |

|

up(LidLayers[3][LENGTH] – LidTopDepth) |

|

for (i=[0:(NumRibs – 1)]) |

|

zrot(i*360/NumRibs + RibAlign) |

|

right(LidLayers[3][ID]/2) |

|

cuboid(Rib,anchor=BOTTOM,rounding=1,edges="Z"); |

|

} |

|

else |

|

down(Expand ? Protrusion : 0) |

|

cyl(LidLayers[3][LENGTH] + (Expand ? 2*Protrusion : 0), |

|

d=(Expand ? 2 : 1)*LidLayers[3][OD],anchor=BOTTOM); |

|

} |

|

} |

|

|

|

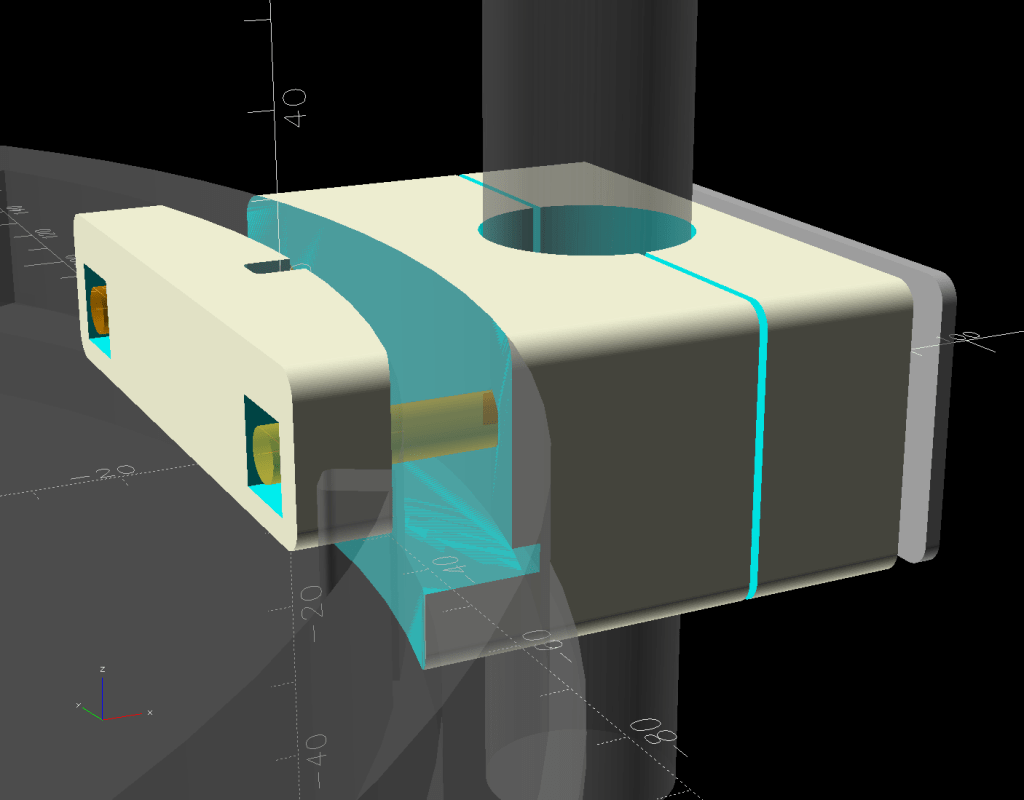

// Mount clamp |

|

|

|

module Mount() { |

|

render() |

|

difference() { |

|

cuboid(MountBlock,anchor=BOTTOM+LEFT,rounding=EdgeRadius,edges="X"); |

|

left(LidLayers[1][OD]/2 – BaseSagitta) |

|

up(LidLayers[1][LENGTH] + LidLayers[2][LENGTH]) |

|

BucketLid(Interior=false); |

|

right(PoleOffset) { |

|

cyl(3*MountBlock.z,d=(PoleOD + HoleWindage.x + 2*TapeThick),circum=true,anchor=CENTER); |

|

cuboid([Kerf,2*MountBlock.y,3*MountBlock.z]); |

|

} |

|

if (false) |

|

right(MountBlock.x – PlateThick) |

|

cuboid(3*[PlateThick,MountBlock.y,MountBlock.z],anchor=LEFT); |

|

up(LidOAH – LidLayers[3][LENGTH]/2) |

|

for (j=[-1,1]) |

|

fwd(j*ScrewOC/2) { |

|

cyl(ScrewLength,d=Screw[ID] + HoleWindage.x,circum=true,orient=RIGHT,anchor=BOTTOM,$fn=6,spin=180/6); |

|

if (false) |

|

right(MountBlock.x + Protrusion) |

|

cyl(Screw[LENGTH] + Protrusion,d=Screw[OD] + HoleWindage.x,circum=true, |

|

orient=LEFT,anchor=BOTTOM,$fn=12,spin=180/12); |

|

} |

|

} |

|

} |

|

|

|

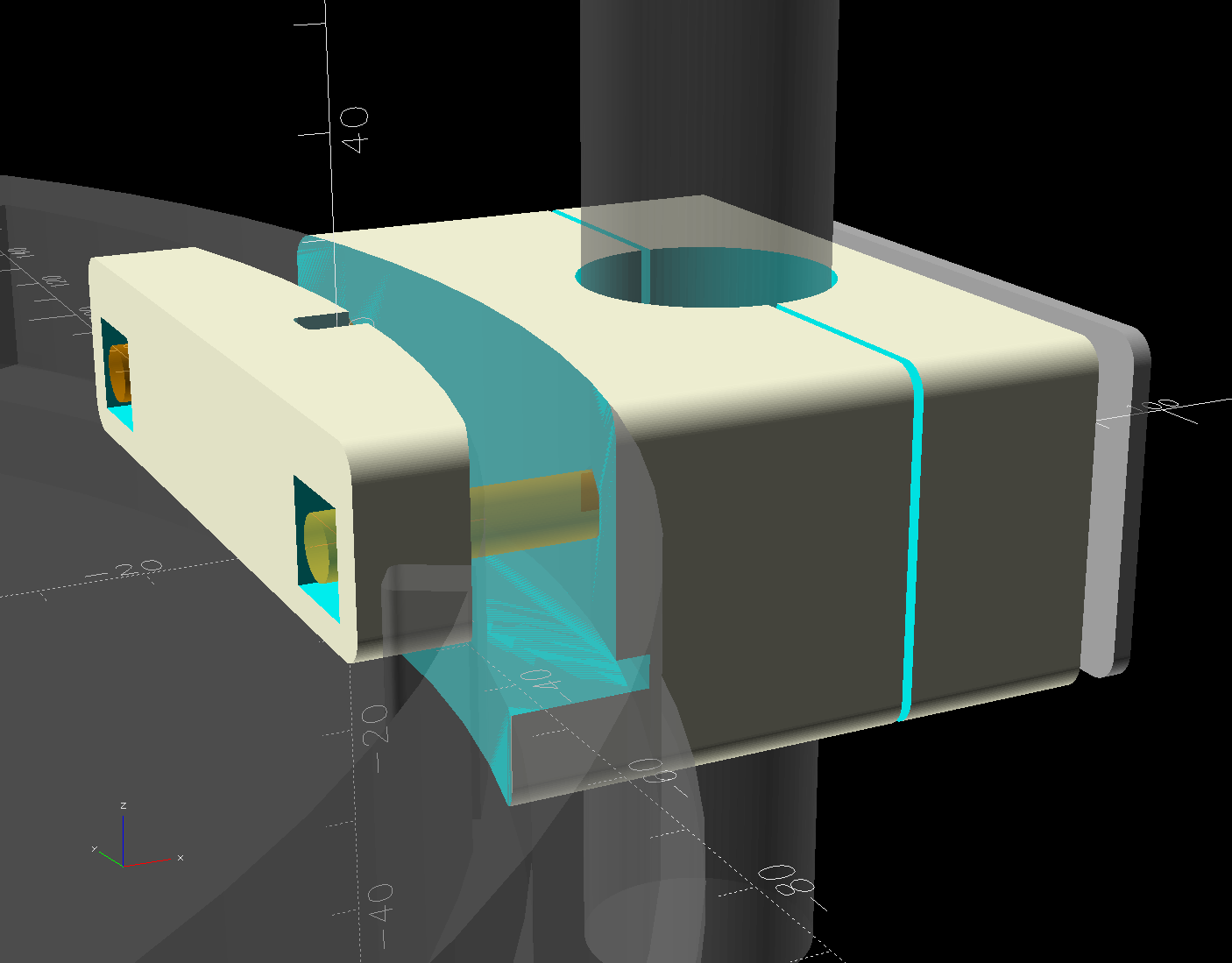

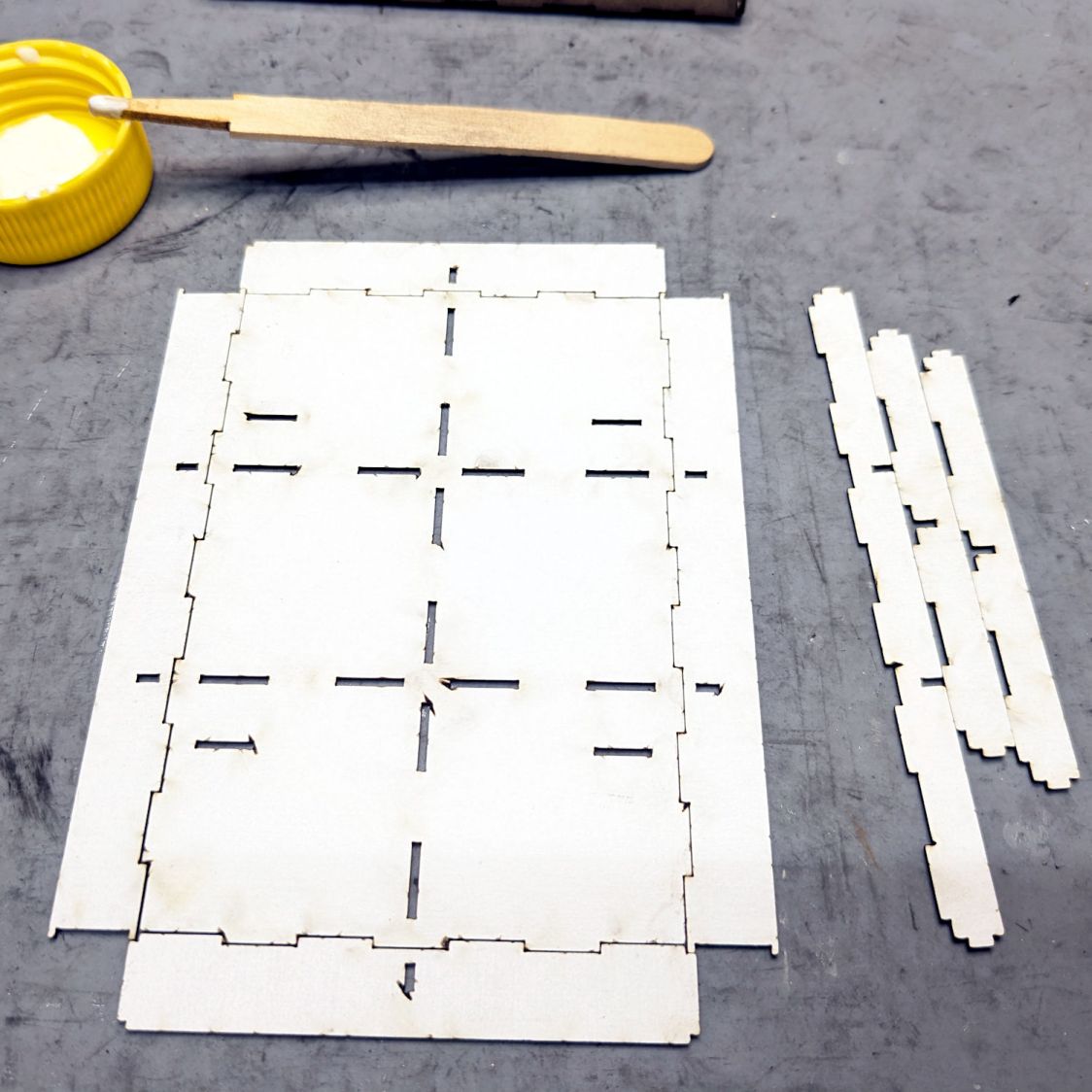

// Nut block segment inside lid |

|

|

|

module NutSegment() { |

|

|

|

render() |

|

difference() { |

|

cuboid(SegmentBlock,anchor=BOTTOM,rounding=EdgeRadius,edges="X"); |

|

down(LidLayers[3][LENGTH] – LidTopDepth) |

|

left(LidLayers[1][OD]/2 – BaseSagitta) |

|

BucketLid(Interior=true,Expand=true); |

|

up(LidTopDepth – LidLayers[3][LENGTH]/2) |

|

for (j=[-1,1]) |

|

fwd(j*ScrewOC/2) { |

|

left(SegmentBlock.x/2) |

|

cyl(ScrewLength,d=Screw[ID],circum=true,anchor=BOTTOM,$fn=6,spin=180/6,orient=RIGHT); |

|

left(SegmentBlock.x/2) |

|

yrot(90) |

|

SquareNut(); |

|

} |

|

} |

|

|

|

} |

|

|

|

//—– |

|

// Build things |

|

|

|

if (Layout == "Lid") |

|

BucketLid(); |

|

|

|

if (Layout == "Mount") |

|

Mount(); |

|

|

|

if (Layout == "Segment") |

|

NutSegment(); |

|

|

|

if (Layout == "Nut") |

|

Rivnut(); |

|

|

|

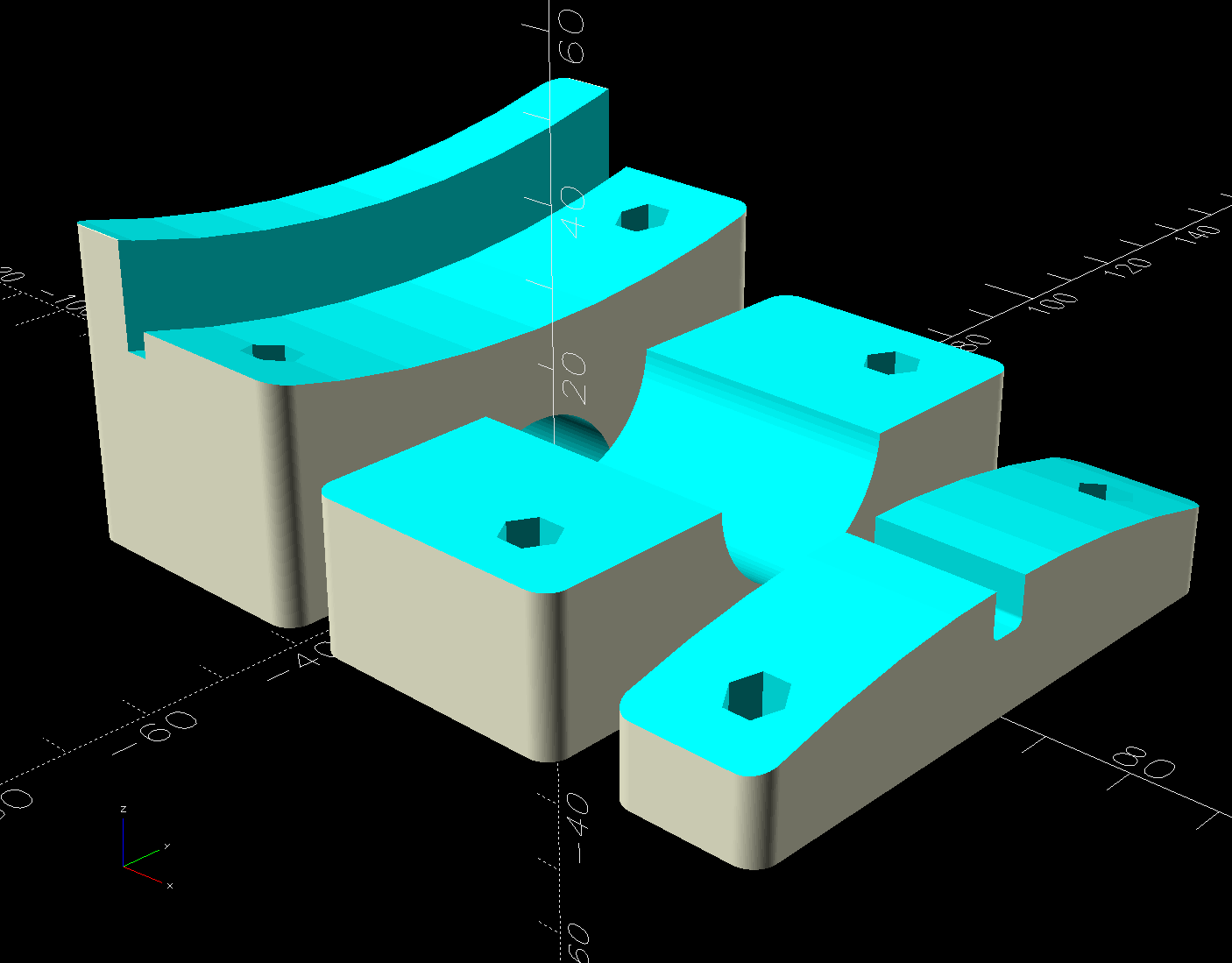

if (Layout == "Show") { |

|

down(LidLayers[1][LENGTH] + LidLayers[2][LENGTH]) { |

|

Mount(); |

|

color("Orange",0.5) |

|

up(LidOAH – LidLayers[3][LENGTH]/2) |

|

right(MountBlock.x + PlateThick) |

|

for (j=[-1,1]) |

|

fwd(j*ScrewOC/2) |

|

cyl(ScrewLength,d=Screw[ID],circum=true,orient=LEFT,anchor=BOTTOM); |

|

} |

|

up(LidLayers[3][LENGTH] – LidTopDepth) |

|

NutSegment(); |

|

|

|

color("Gray",0.4) |

|

right(PoleOffset) |

|

cylinder(3*MountBlock.z,d=(PoleOD),anchor=CENTER); |

|

color("Gray",0.4) |

|

left(LidLayers[1][OD]/2 – BaseSagitta) |

|

BucketLid(); |

|

color("White",0.7) |

|

down(LidLayers[1][LENGTH] + LidLayers[2][LENGTH]) |

|

right(MountBlock.x + 2*PlateThick) |

|

difference() { |

|

cuboid([PlateThick,MountBlock.y,MountBlock.z],anchor=BOTTOM+LEFT,rounding=EdgeRadius,edges="X"); |

|

up(LidOAH – LidLayers[3][LENGTH]/2) |

|

for (j=[-1,1]) |

|

fwd(j*ScrewOC/2) |

|

cyl(ScrewLength,d=Screw[ID],circum=true,orient=RIGHT,anchor=CENTER); |

|

} |

|

} |

|

|

|

if (Layout == "Build") { |

|

render() |

|

union() { |

|

difference() { |

|

left(MountBlock.z + Gap/2) |

|

up(PoleOffset – Kerf/2) |

|

yrot(90) |

|

Mount(); |

|

cuboid([3*MountBlock.z,2*MountBlock.y,3*MountBlock.x],anchor=TOP); |

|

} |

|

render() |

|

right(Gap/2) |

|

intersection() { |

|

up(MountBlock.x) |

|

yrot(90) |

|

Mount(); |

|

up(MountBlock.x – PoleOffset) |

|

right(MountBlock.z/2) |

|

cuboid([2*MountBlock.z,2*MountBlock.y,MountBlock.x],anchor=TOP); |

|

} |

|

right(2*MountBlock.z – BaseSagitta) |

|

up(SegmentBlock.x/2) |

|

yrot(-90) |

|

NutSegment(); |

|

} |

|

} |