The workbench originally in Mary’s Sewing Room became my new desk, which meant installing my pull-out keyboard / trackball tray in place of its drawers:

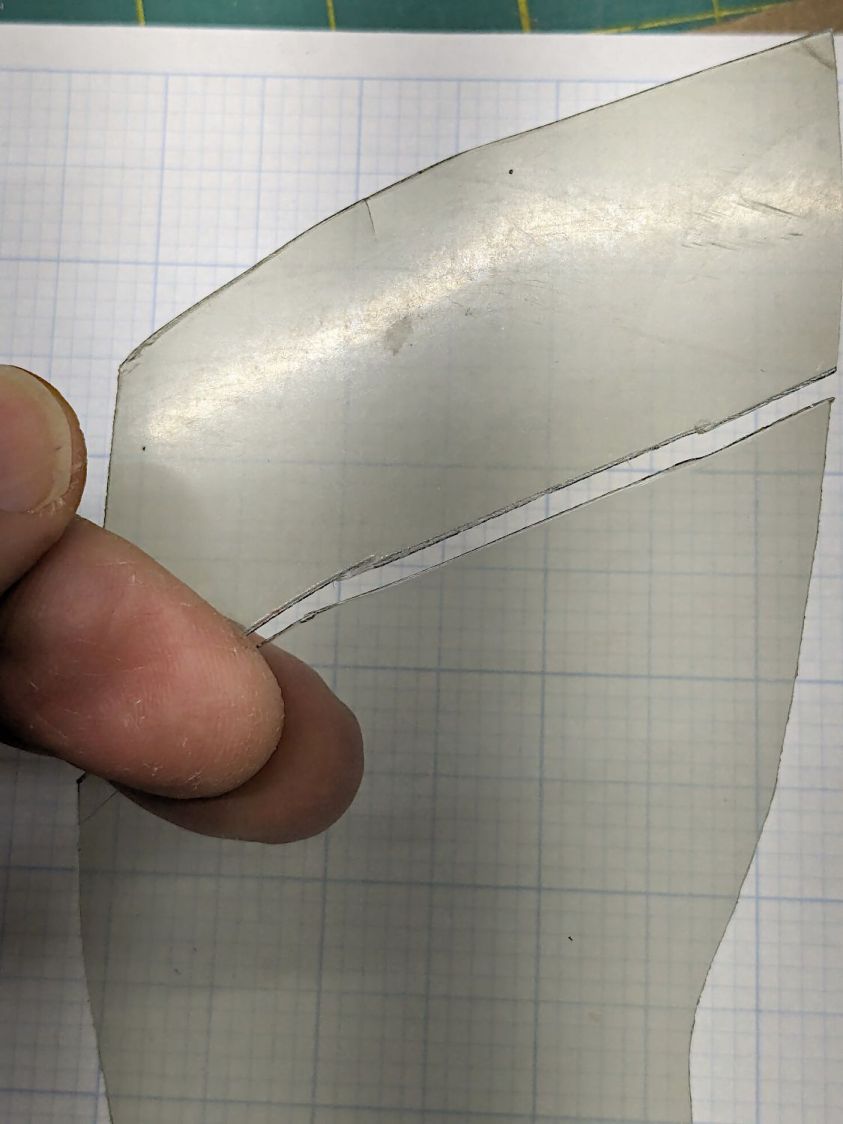

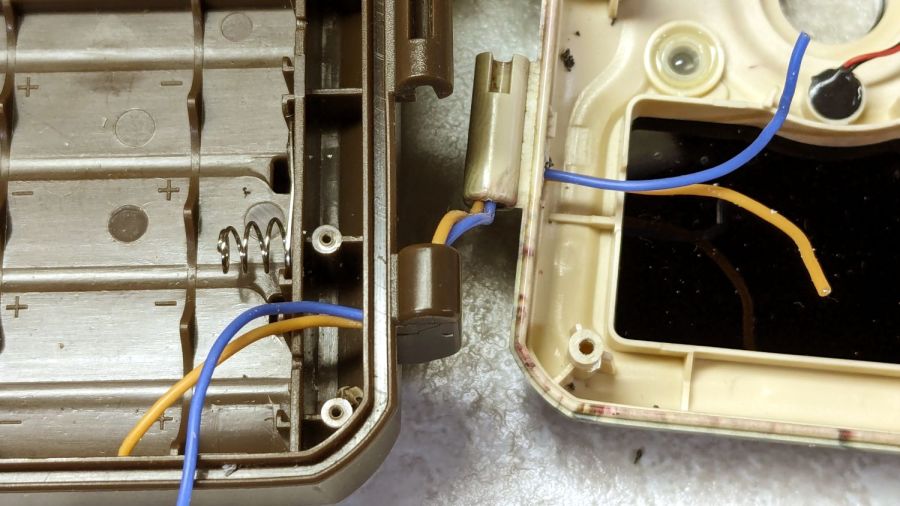

Which required re-gluing the old wood strips of the side slides to their backing plates, as they’d worked loose over the decades:

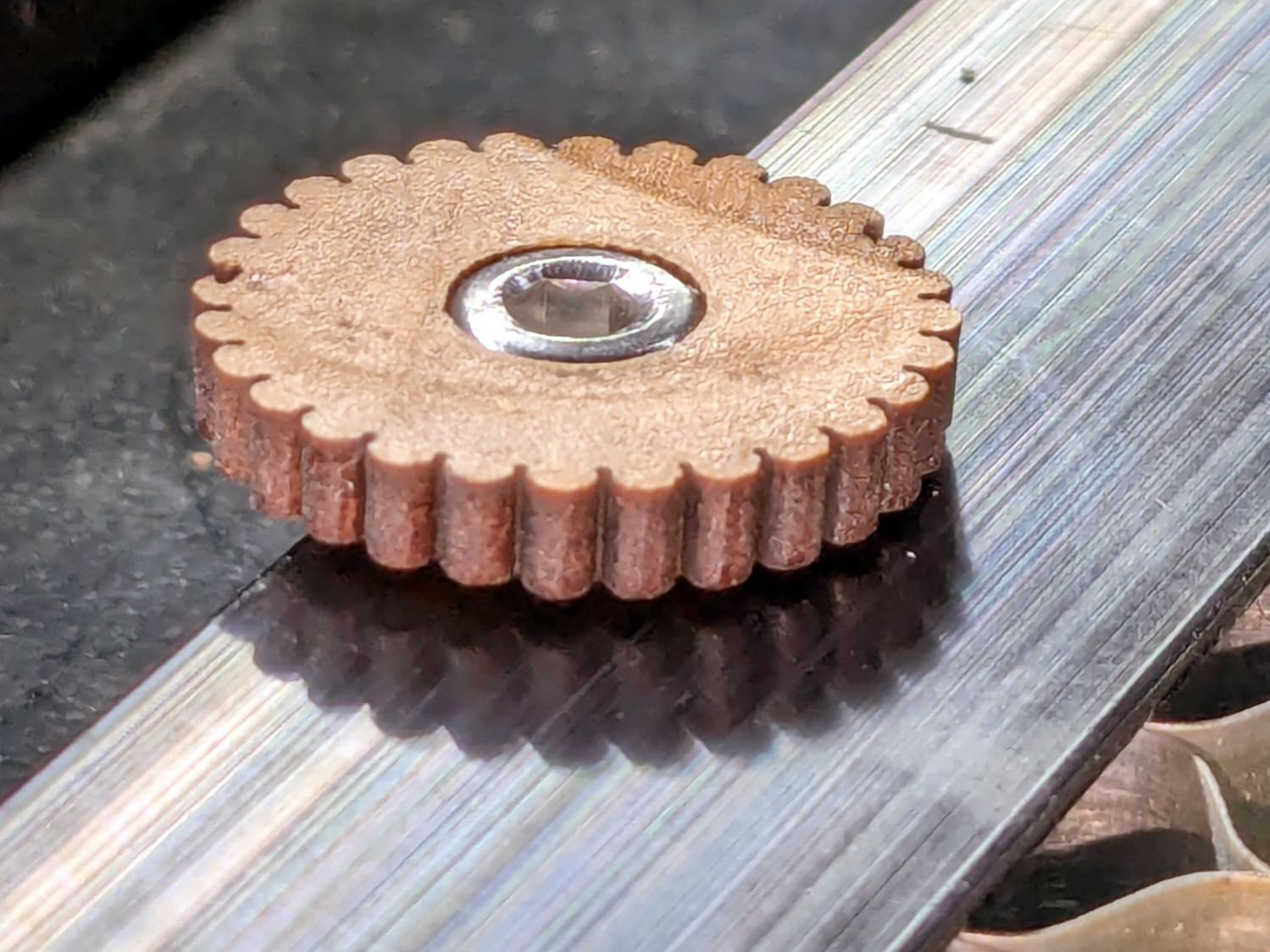

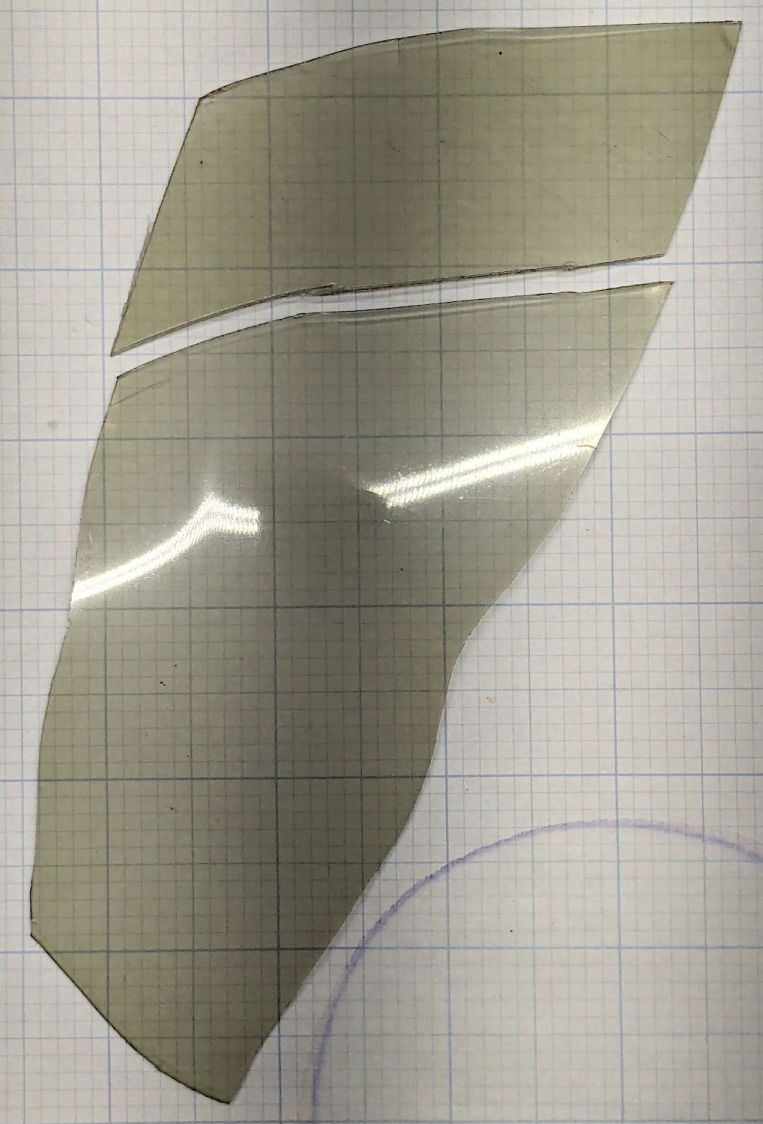

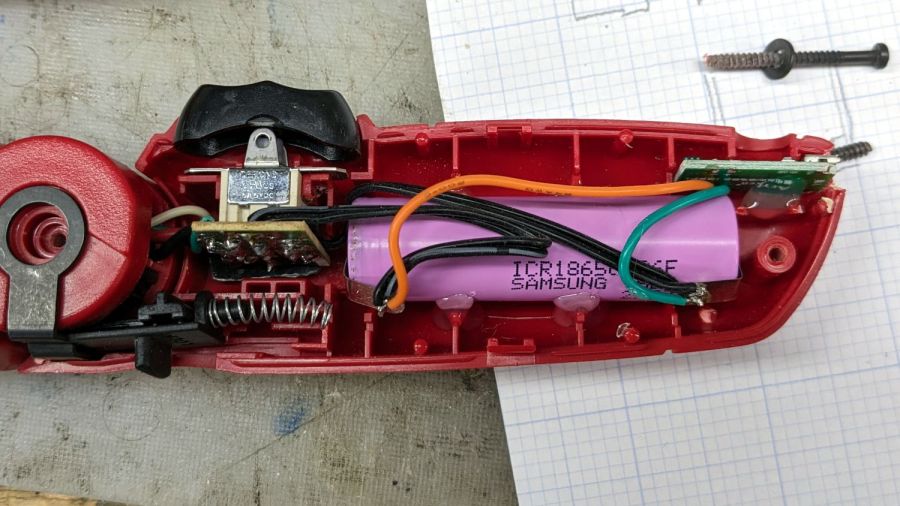

I drilled & screwed three more threaded wood inserts into the bottom of the bench top to hold brackets (cut from those longsuffering maple library shelves) for the side slides:

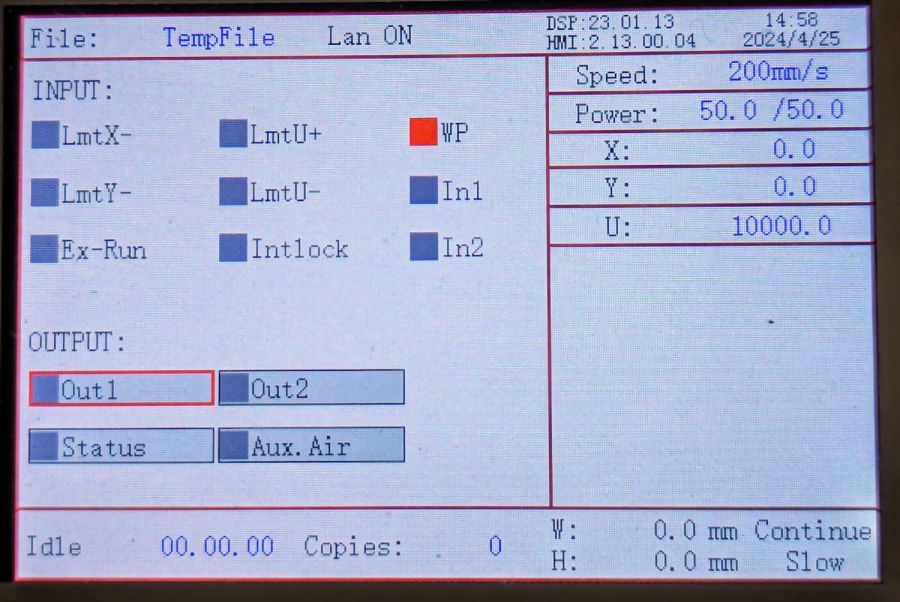

The gray angle brackets came from a long-gone (and sorely missed) radial arm saw, hacksawed to fit on either side of the central beam supporting the workbench top, and held with machine screws in those inserts. Yes, the rear bracket has only a single screw, but it doesn’t support much of a load and it’s not going anywhere.

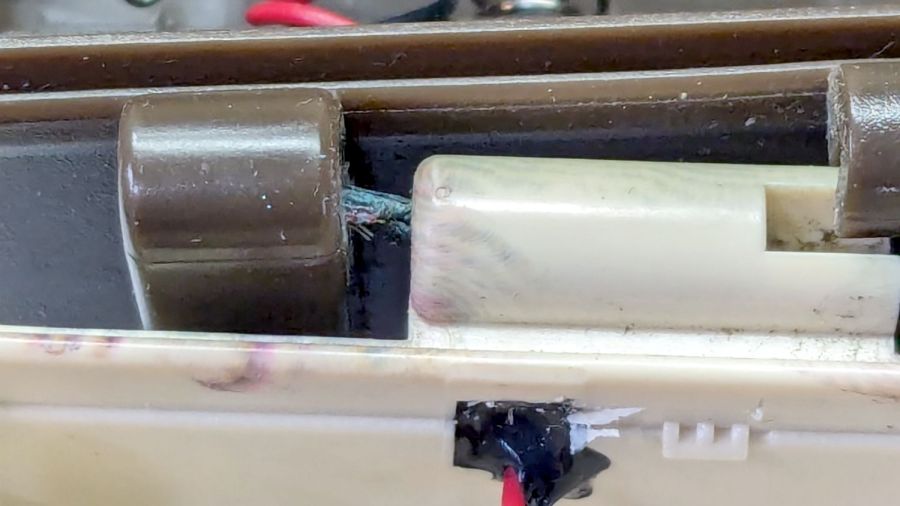

With that in place, the drawers kicked around the basement for a few weeks and eventually ended up under a workbench that Came With The House™ and was likely built by the original owners half a century ago:

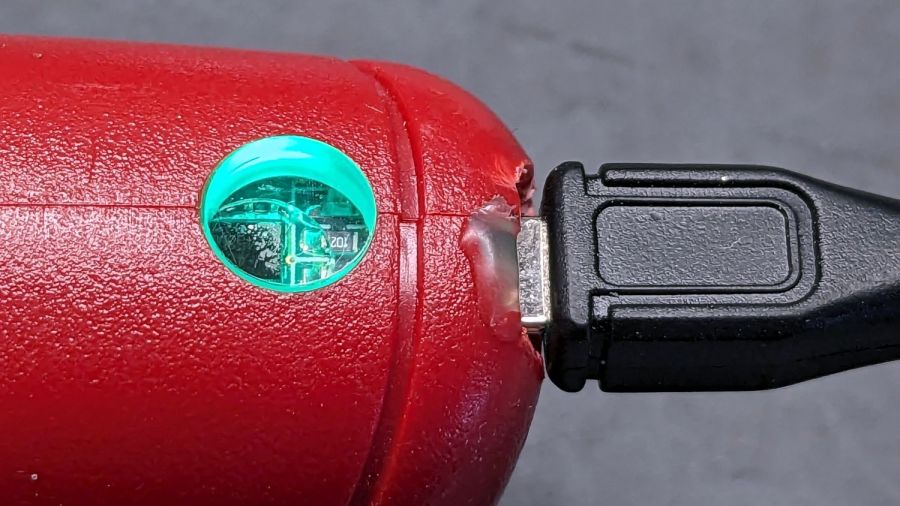

The top is made of 2×6 boards, now topped with laminate planks (left over from when I re-floored the previous kitchen), so the 2×6 board in the middle holds the whole top together and is not removable. I conjured strips at the ends to support the drawer assembly:

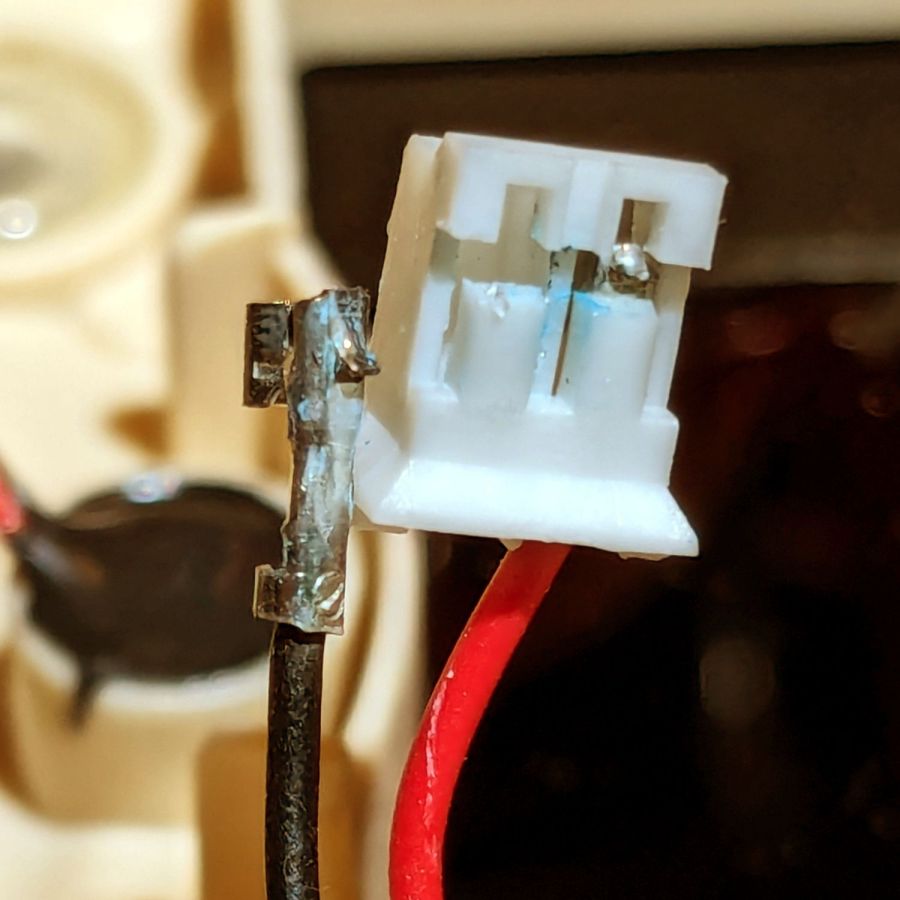

The strips came from the crate around the laser cutter, so they’re made of the cheapest Chinese plywood and entirely suitable for the purpose. The drawers hang from 1/4-20 bolts screwed into tee nuts recessed in the top surface of the strips, with the strips held by deck screws in those benchtop 2×6 planks.

Yeah, both of those are bodges, but they ought to work just fine.