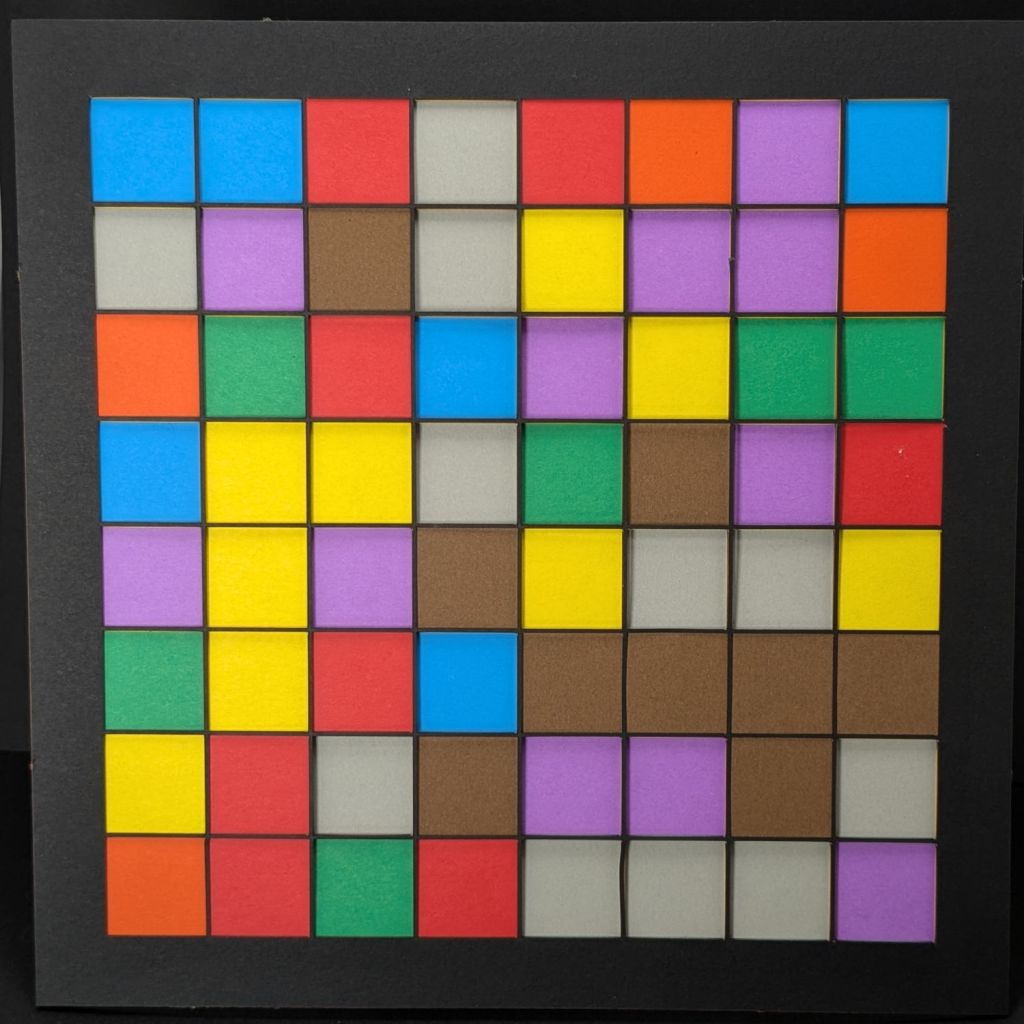

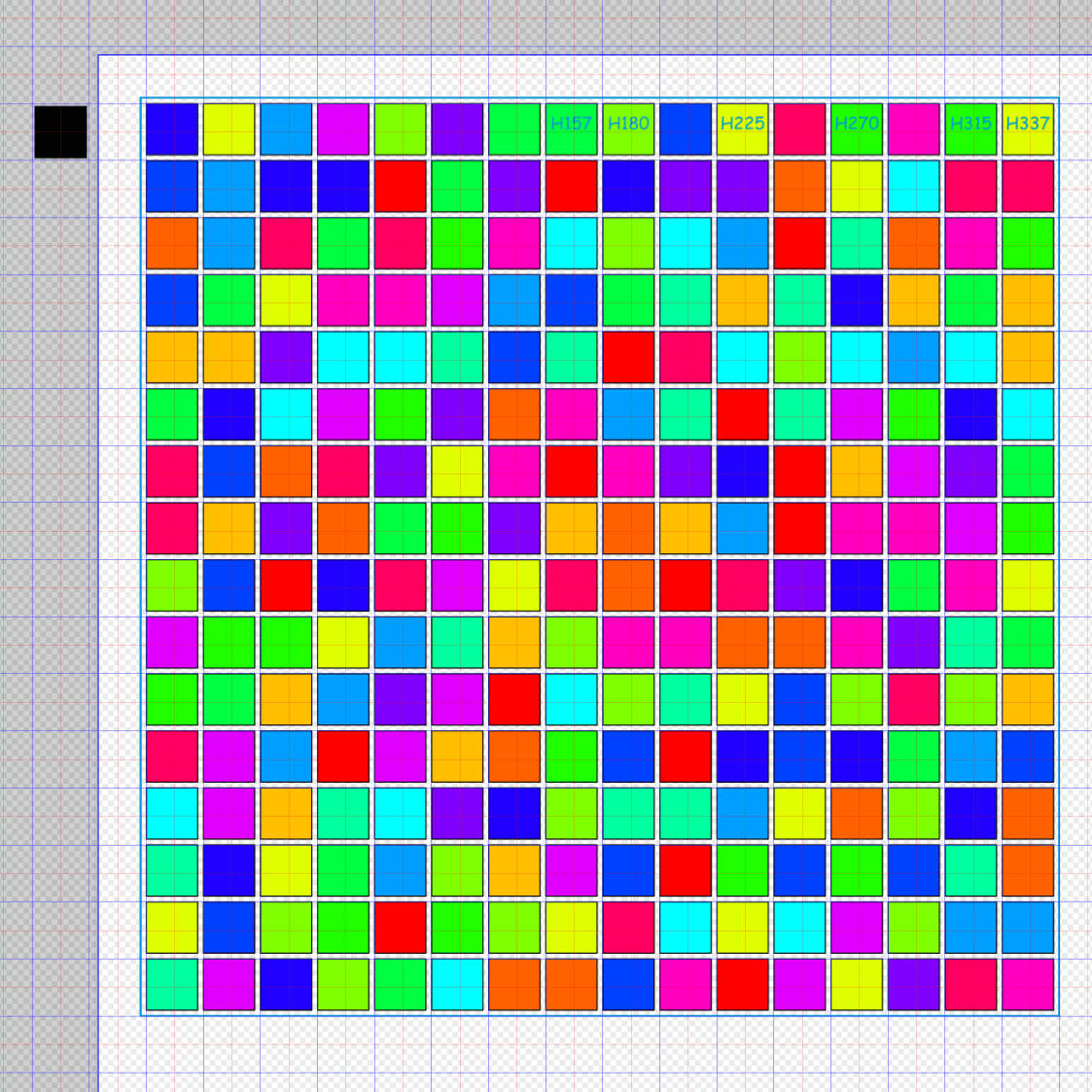

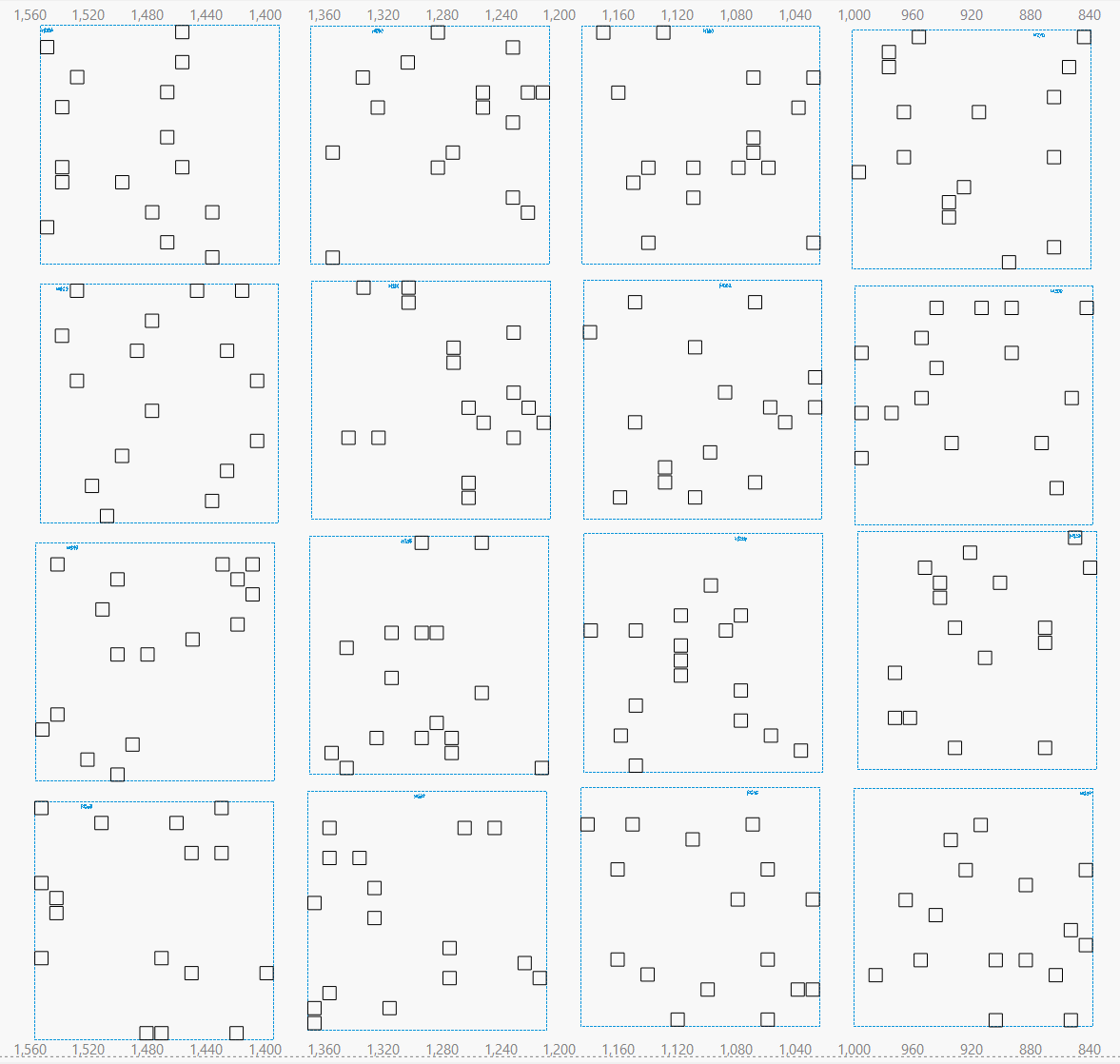

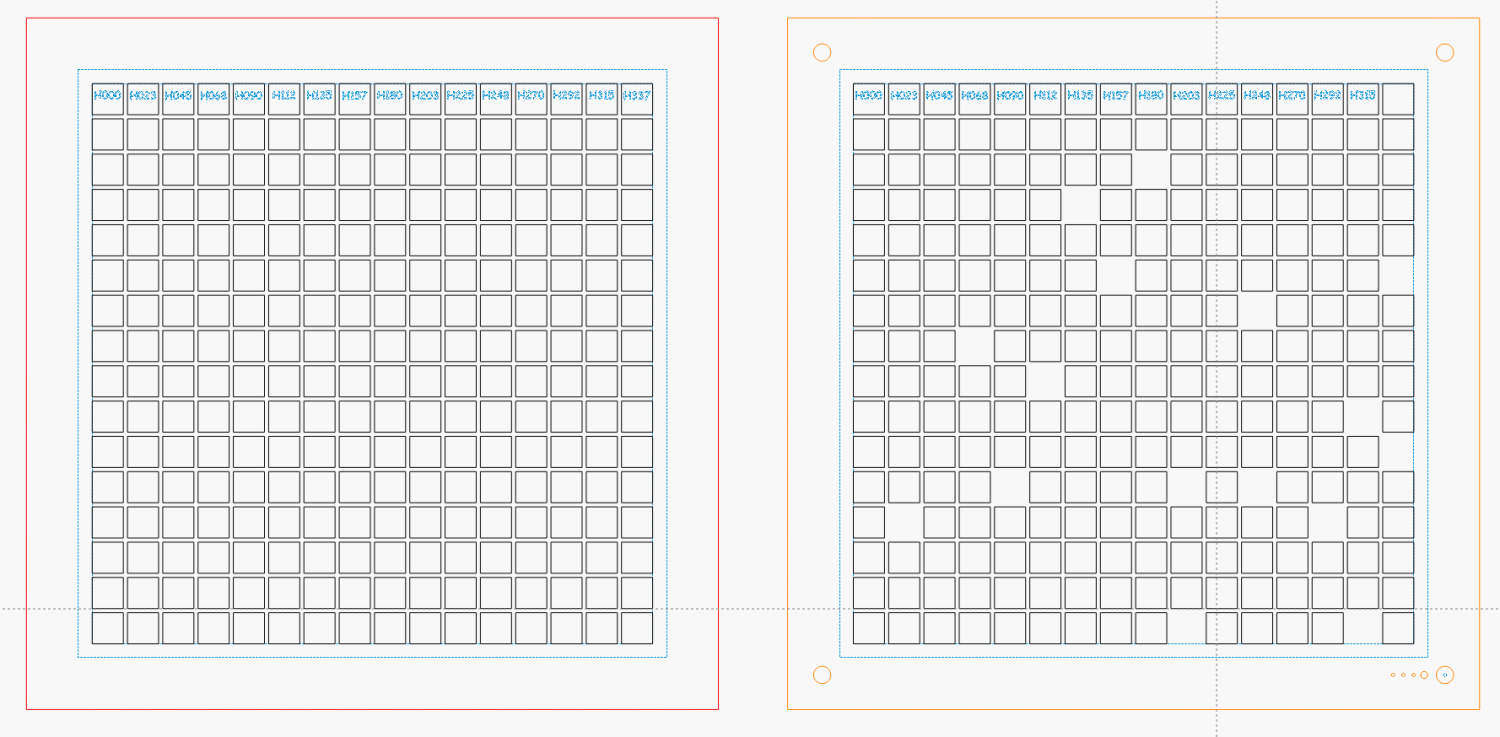

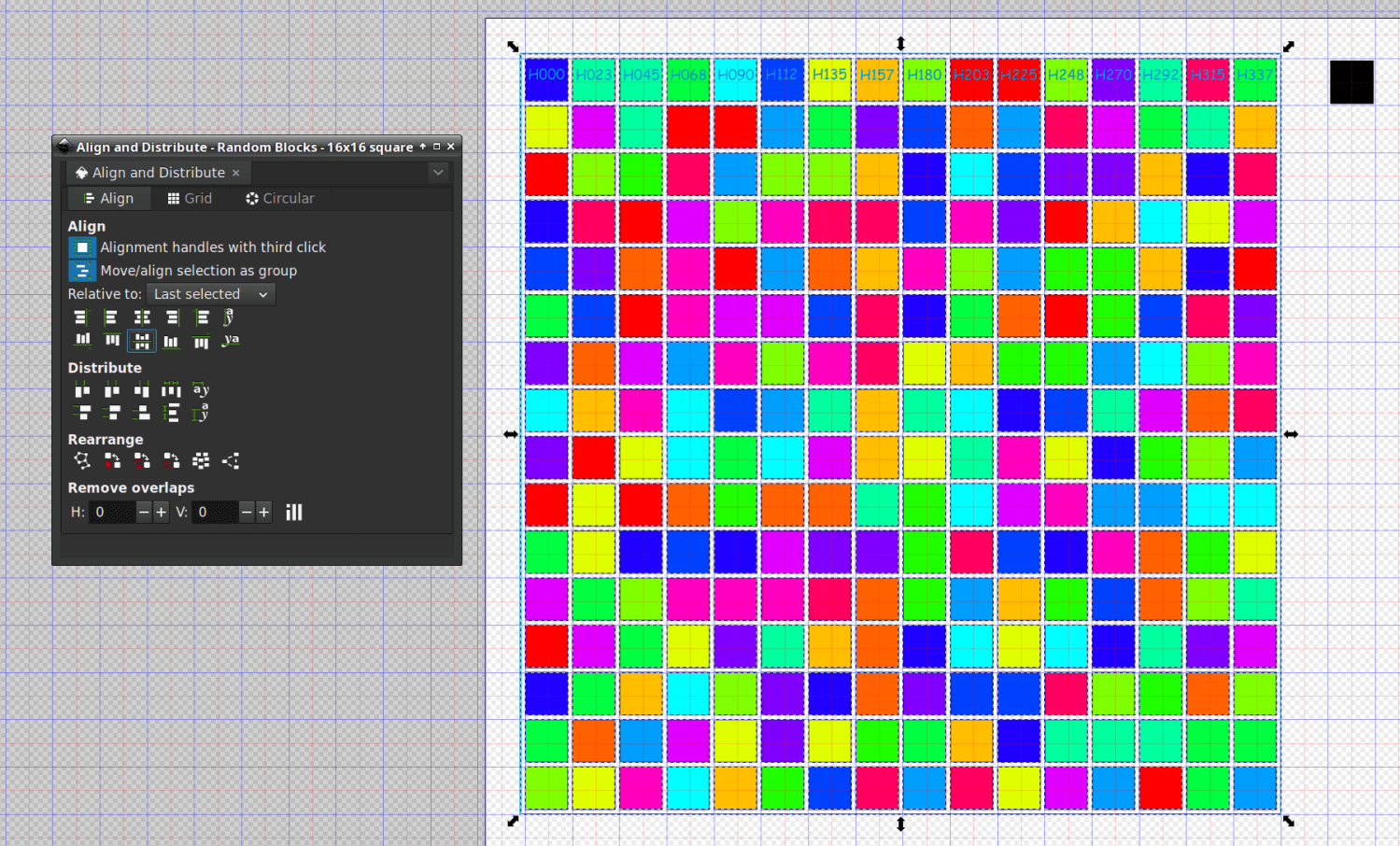

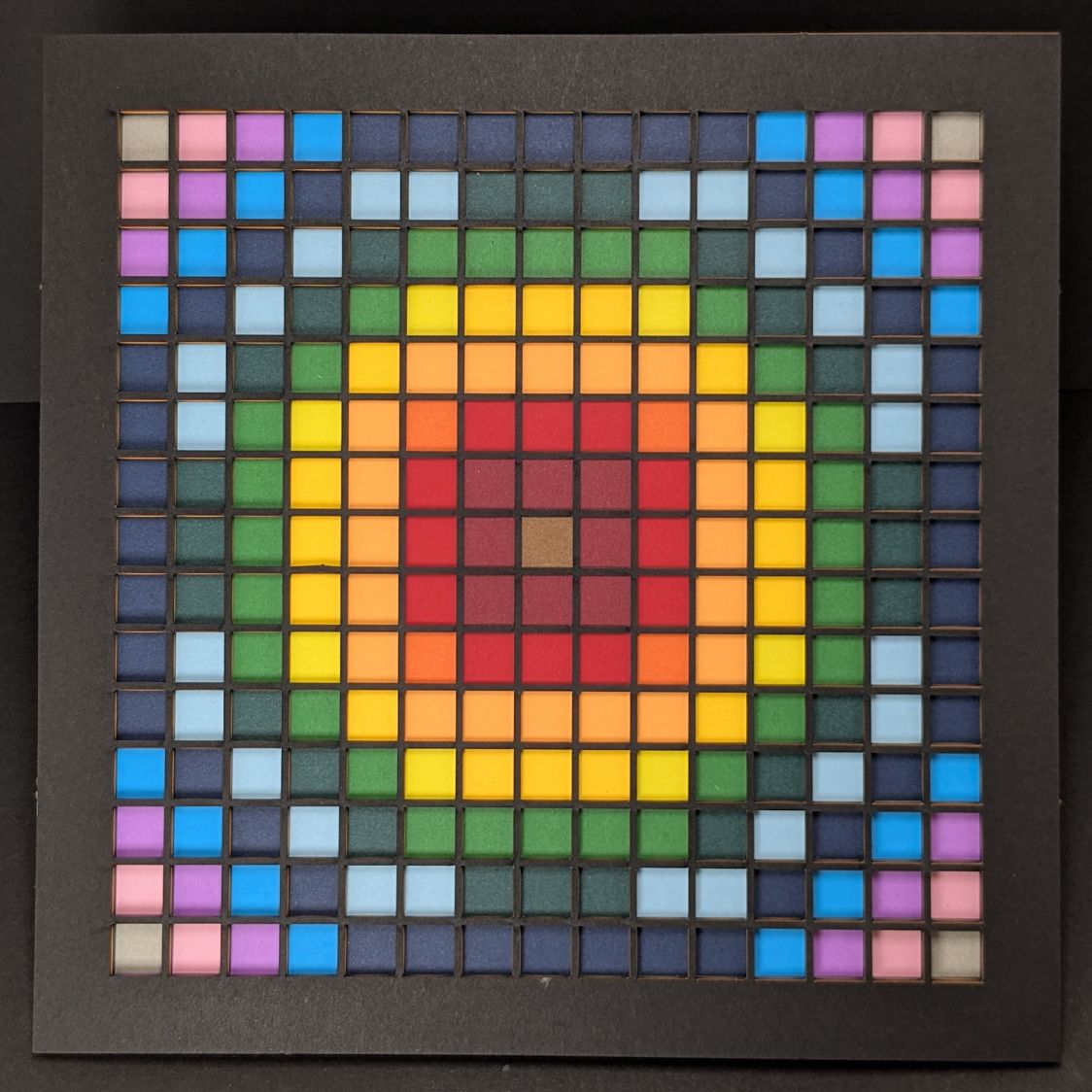

Changing the formula generating the matrix values and cleaning up some infelicitous code choices produces a much more pleasing result:

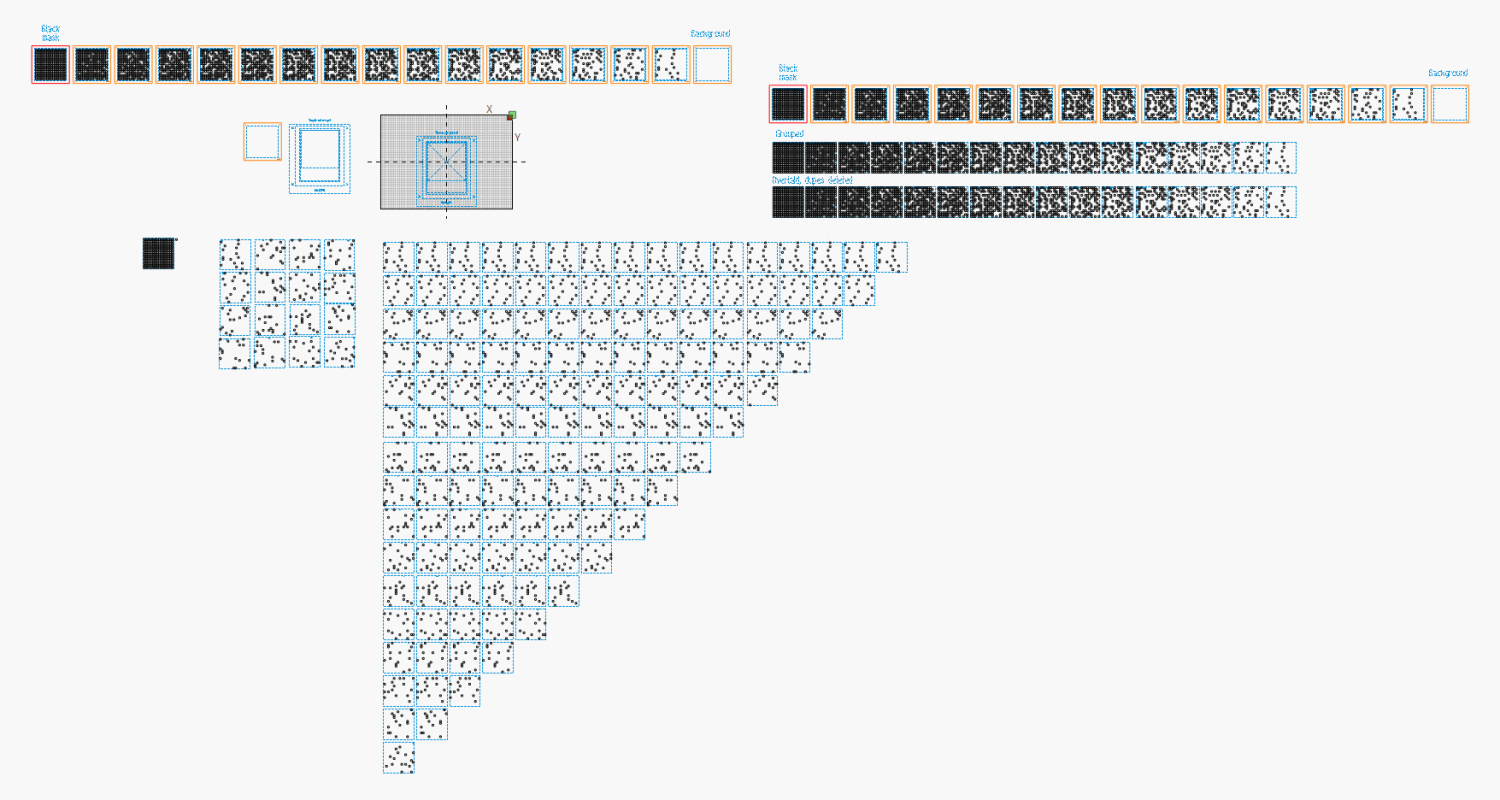

The random squares still look OK, though:

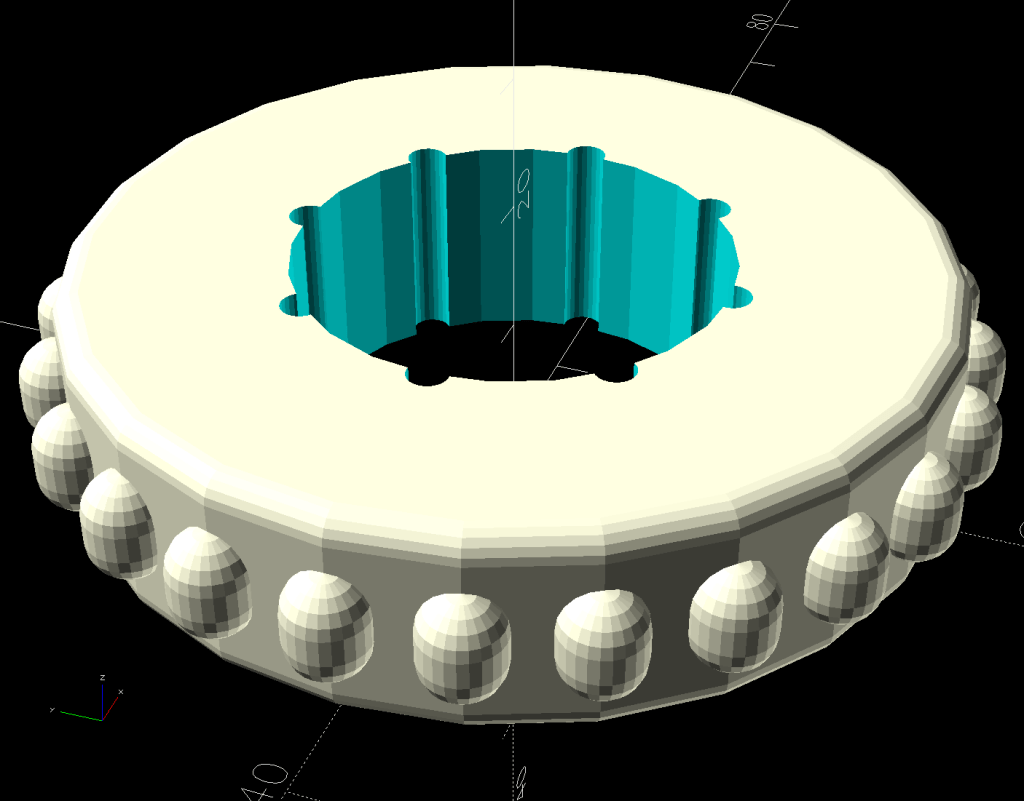

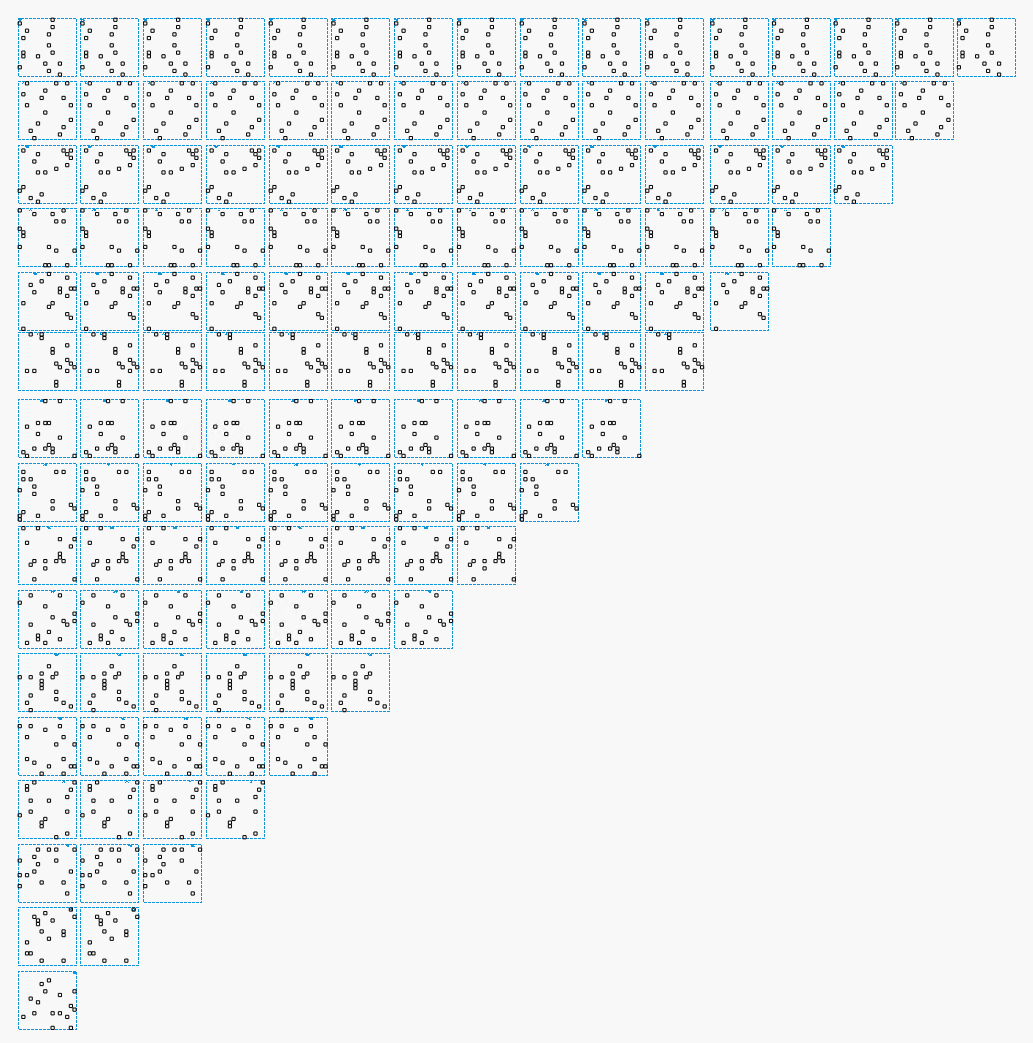

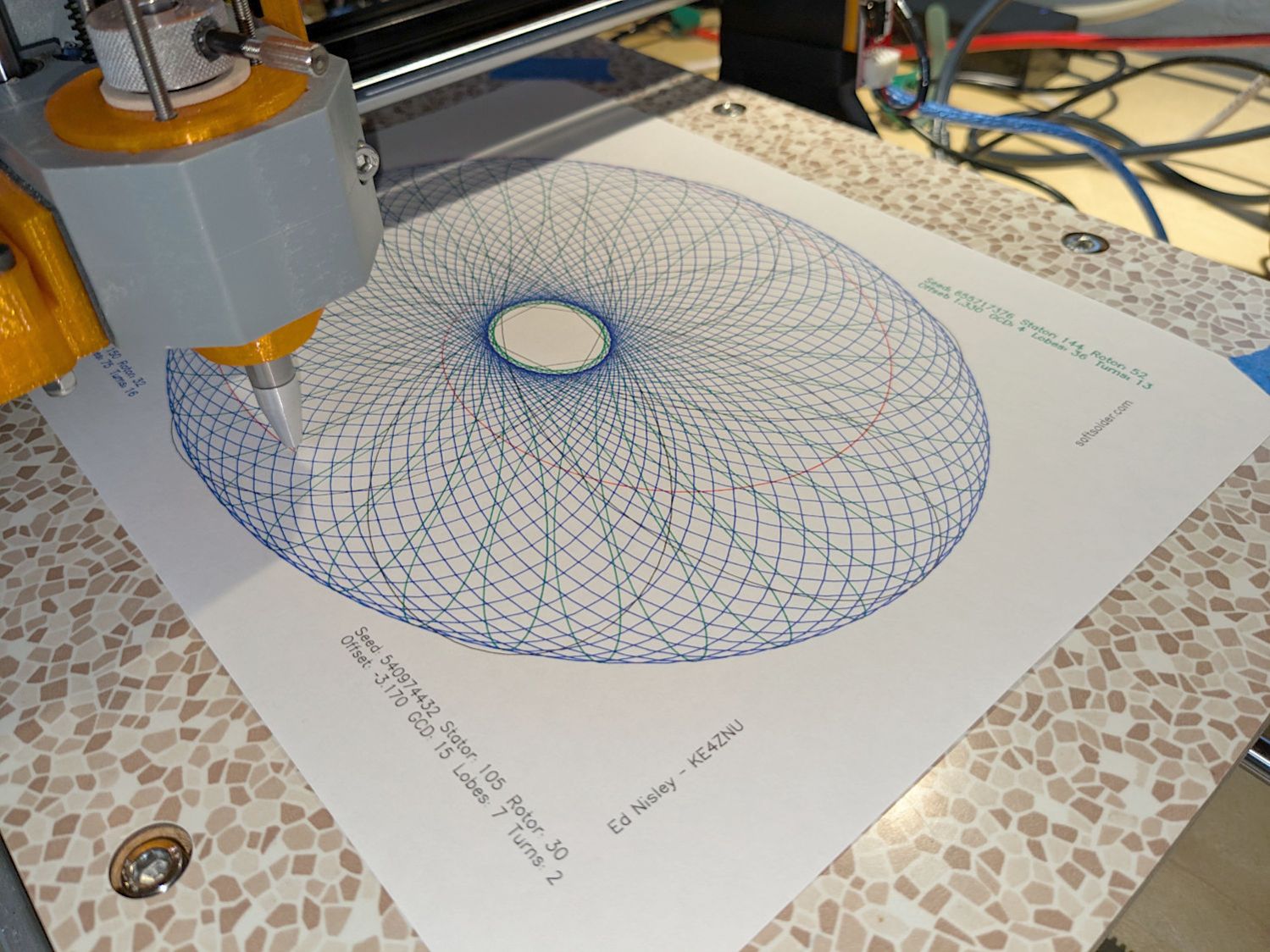

Thresholding the distance from a randomly chosen point creates circular rainbows:

CenterPoint = (choice(range(args.width)),choice(range(args.height)))

CellMatrix = [[math.hypot(x - CenterPoint[X],y - CenterPoint[Y])

for y in range(args.height)]

for x in range(args.width)]

dmax = max(list(chain.from_iterable(CellMatrix)))

LayerThreshold = (ThisLayer/Layers)*dmax

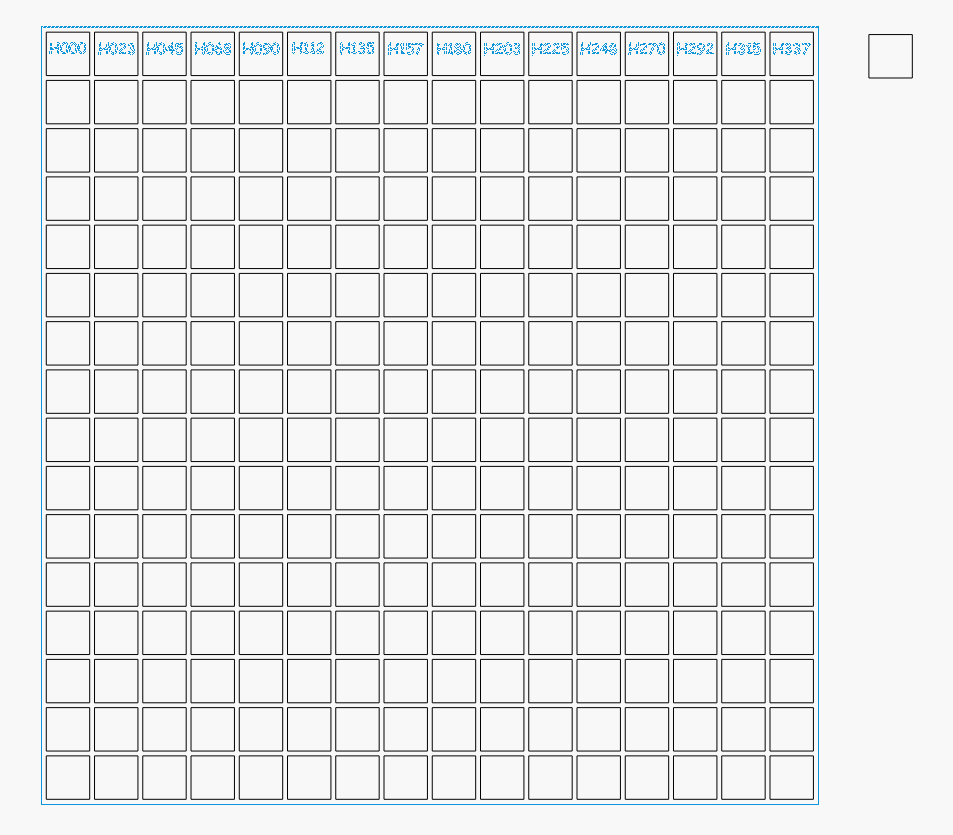

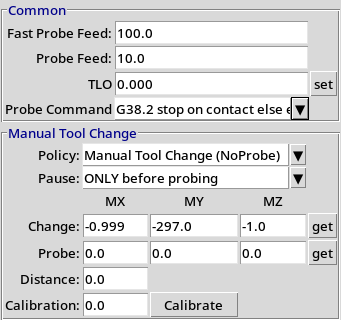

The Python program generates one SVG image file representing a single layer, as determined by the Bash one-liner invoking it:

for i in {00..16} ; do python Layers\ -\ 200mm.py > Test_$i.svg ; done

In real life you’d also use a different random seed for each set of layers, but that’s just another command line optIon.

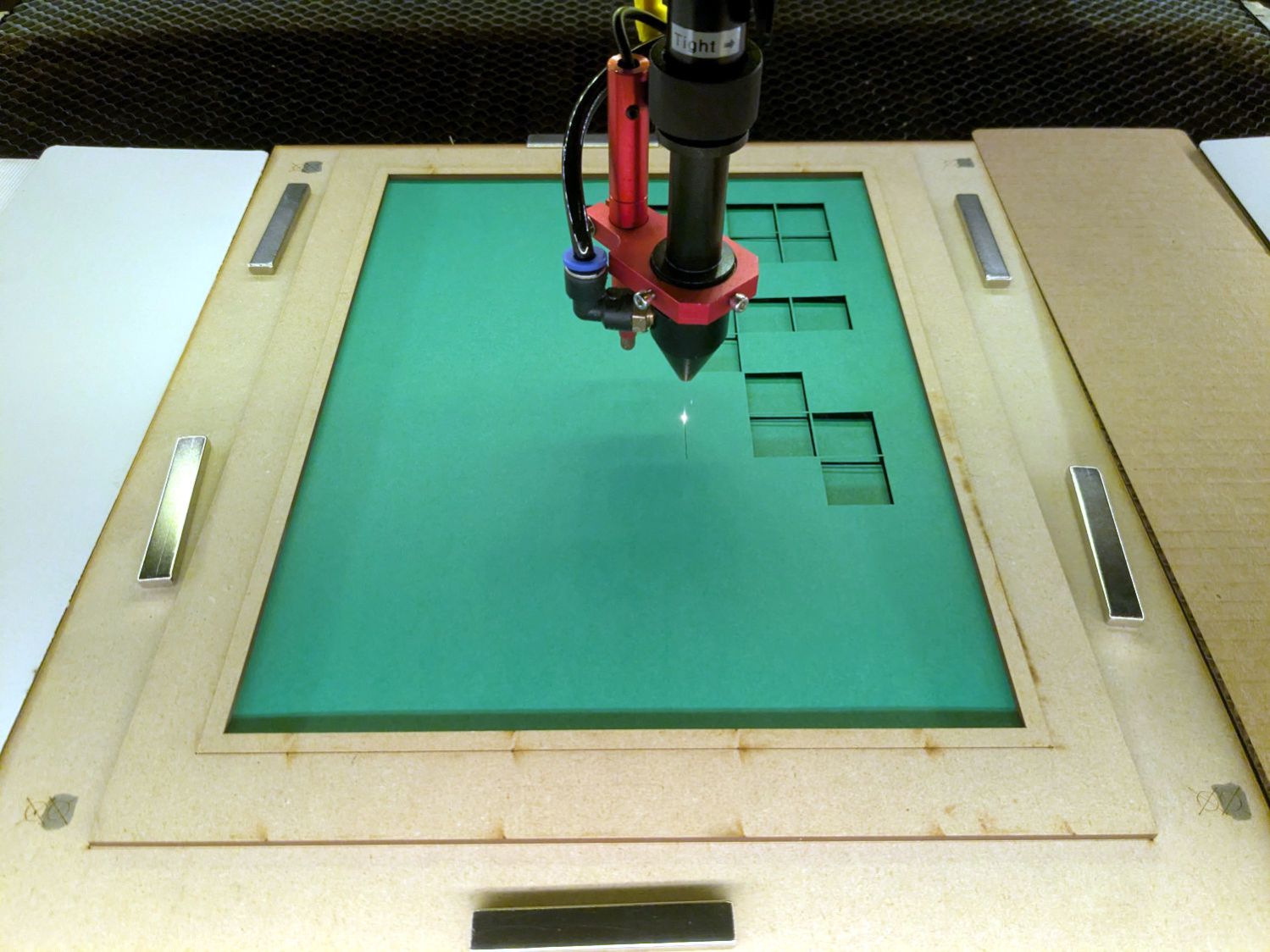

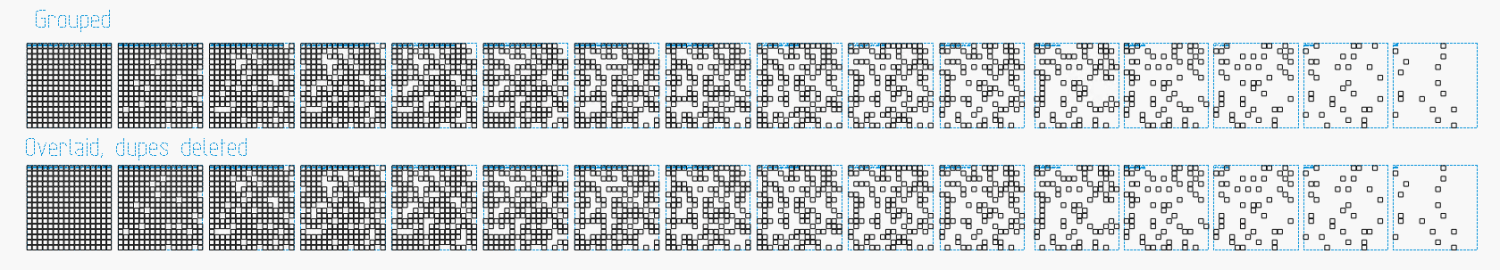

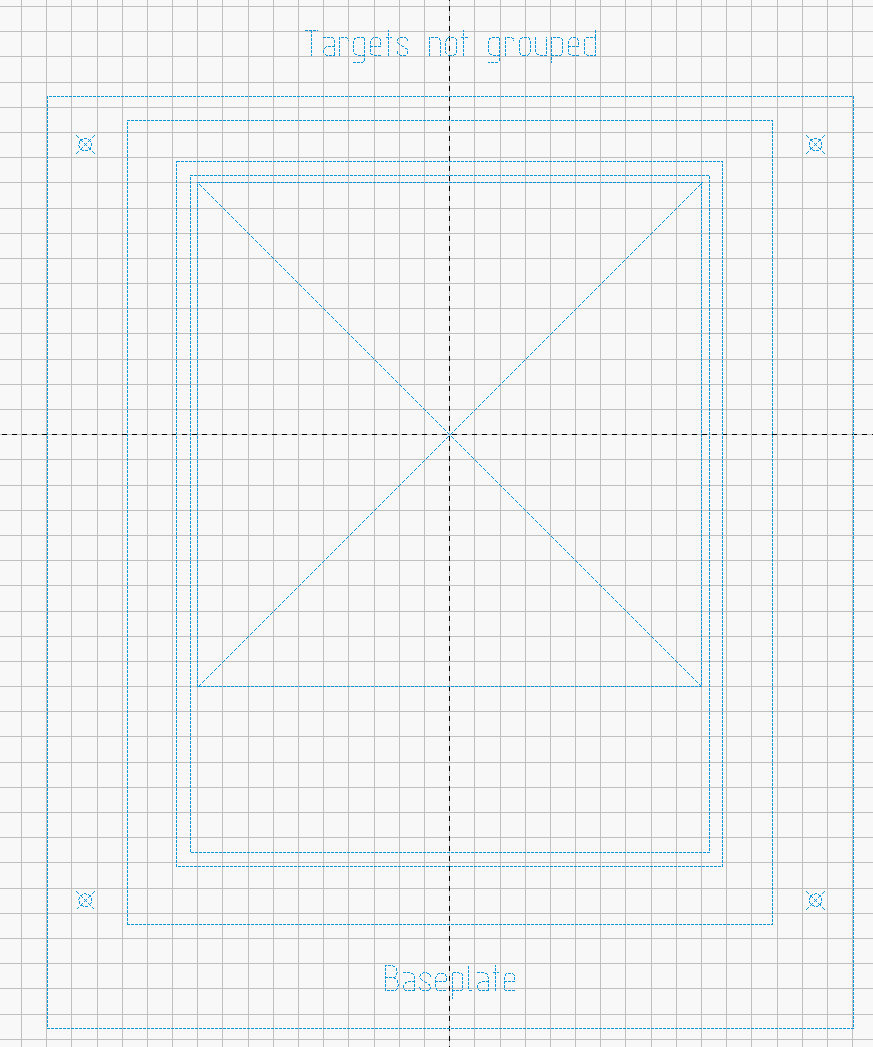

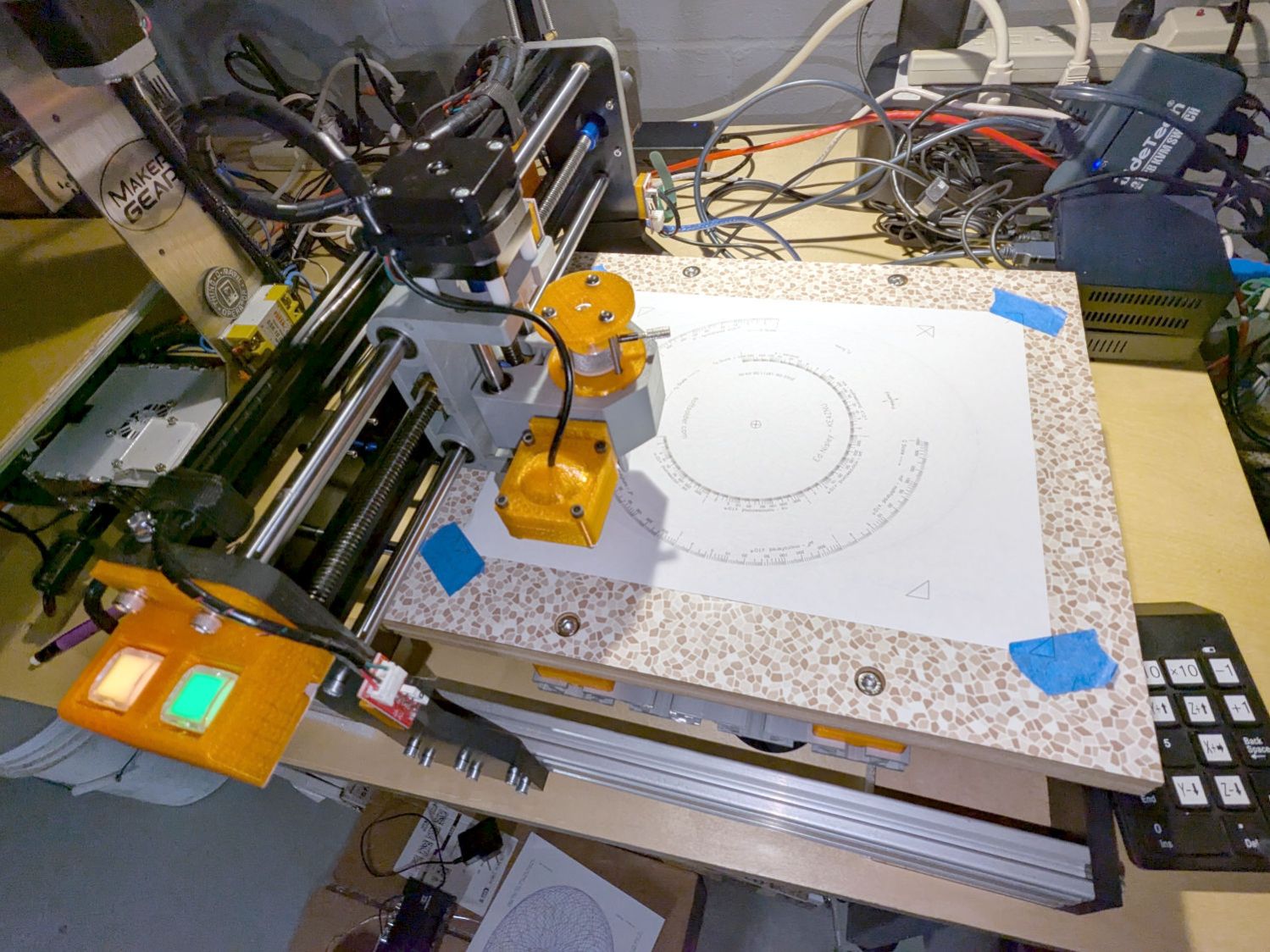

Import those 17 SVG images into LightBurn, arrange neatly, snap each one to the middle of the workspace grid (and thus the aligned template), then Fire The Laser:

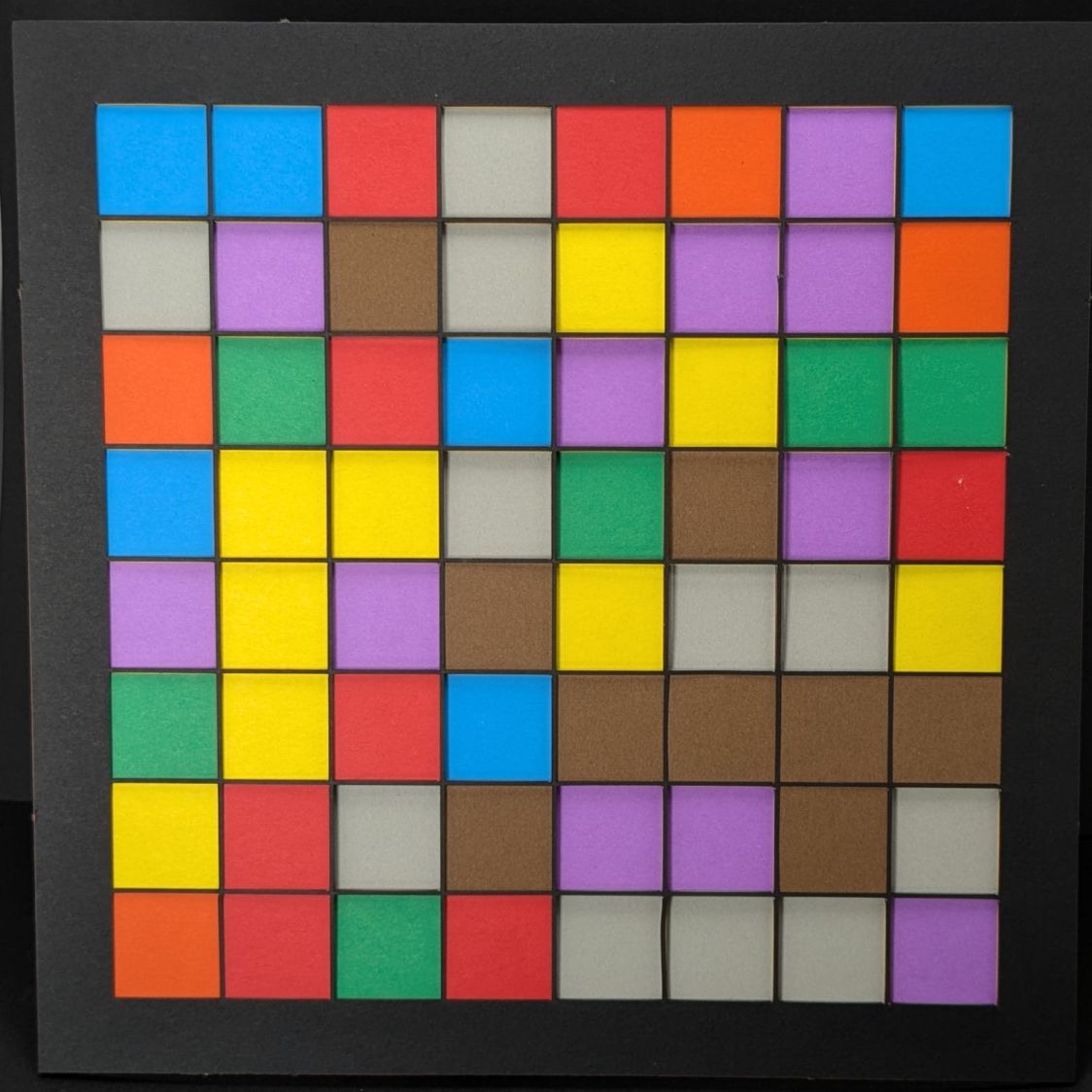

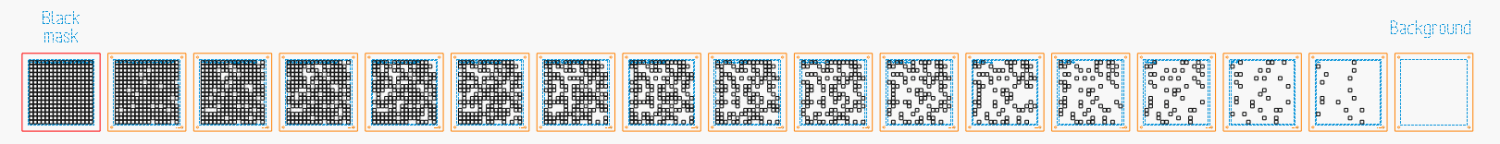

Feeding paper into the laser in rainbow (actually, heavily augmented / infilled EIA color code) order, plus the black mask, produces the aforementioned pleasing result:

Glue the sheets in the assembly fixture:

The white layer is uncut, other than the four alignment holes (with a rivnut poking up) and its binary layer number (16, backwards because upside-down), and appears in only the farthest corners of the rainbow.

Protip: doing the stack upside-down means you smear glue stick on the hidden side of each sheet. If you avoid slobbering glue into the cut square holes, nothing can go wrong.

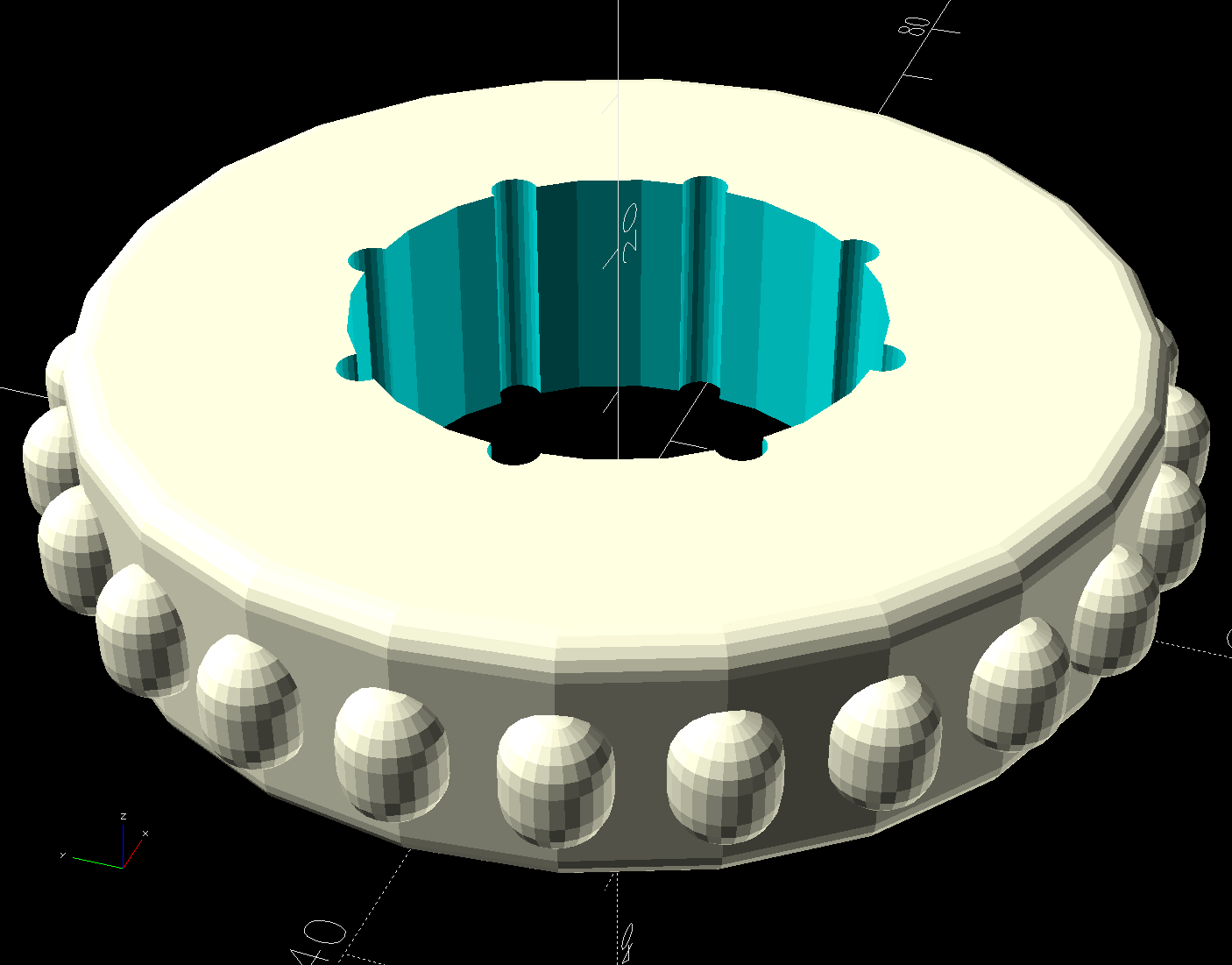

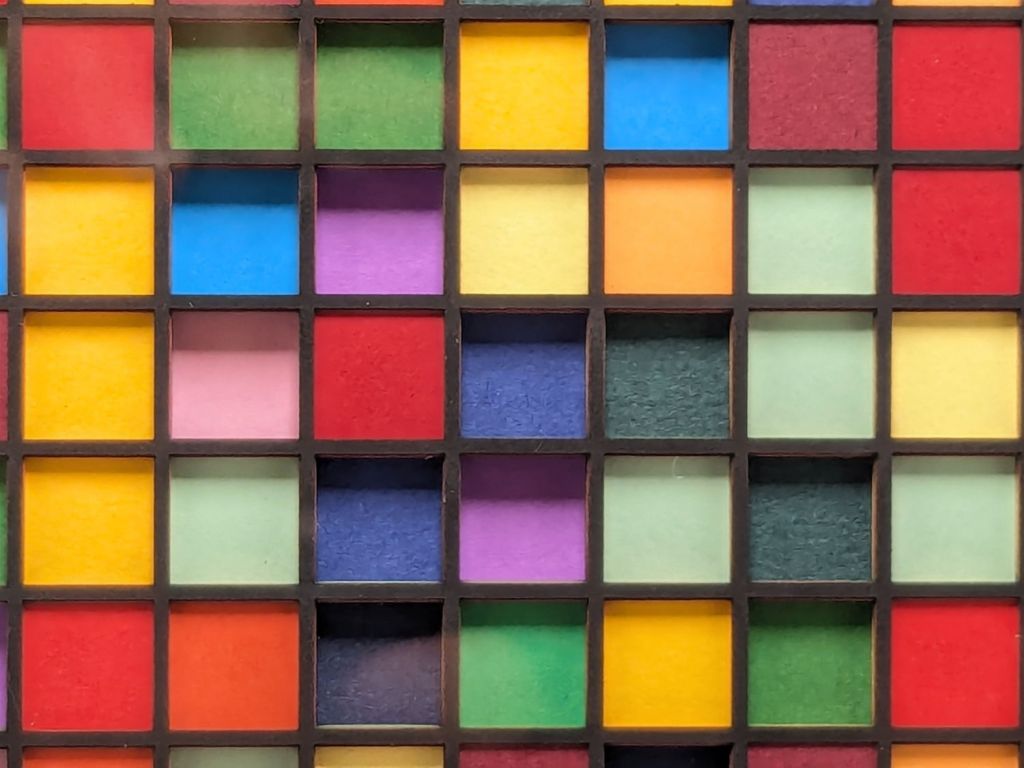

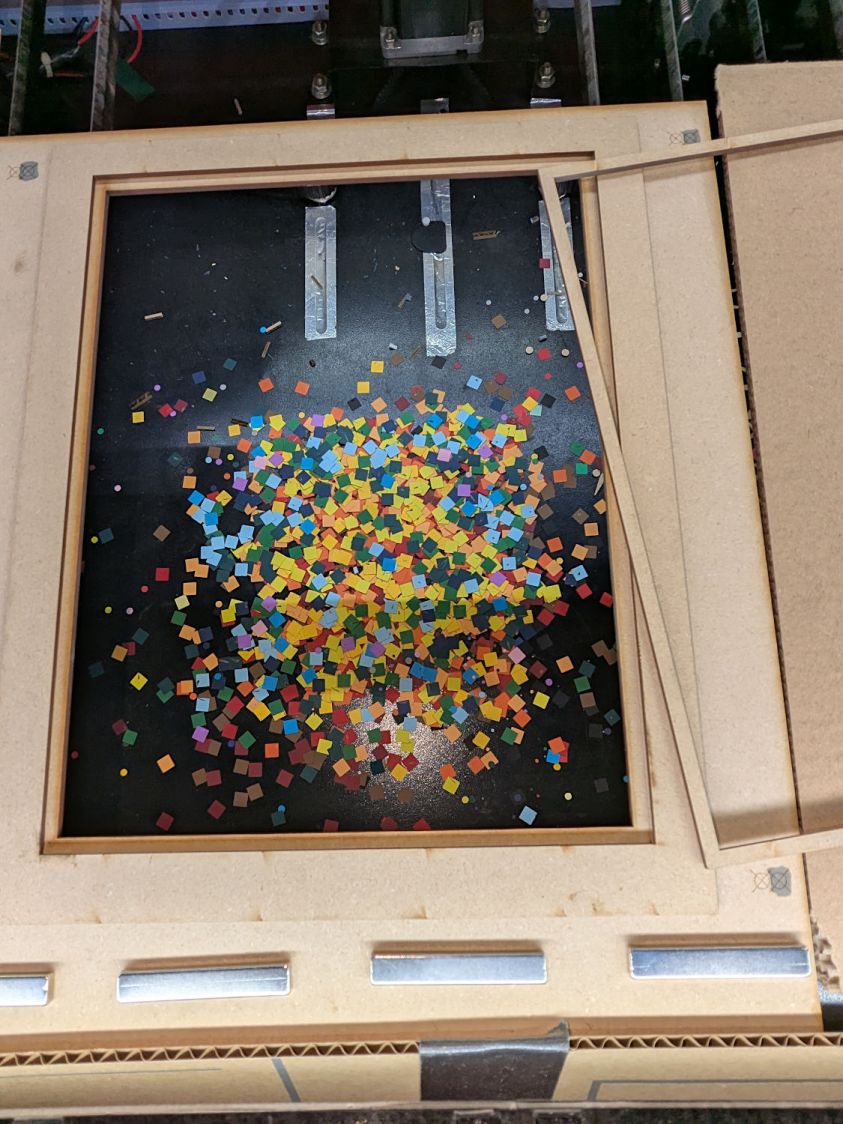

Making these things produces the happiest chip tray ever:

I swept half a dozen pictures worth of squares into a small box and gave it away to someone with a larger small-child cross-section than mine, whereupon a slight finger fumble turned the contents into a glitter bomb. Sorry ’bout that.

The Python source code as a GitHub Gist:

| # Generator for rainbow block layered paper | |

| # Ed Nisley – KE4ZNU | |

| # 2025-08-03 cargo-culted from svg library examples | |

| import svg | |

| import math | |

| from argparse import ArgumentParser | |

| from random import randint, choice, seed | |

| from itertools import chain | |

| from pprint import pprint | |

| INCH = 25.4 | |

| X = 0 | |

| Y = 1 | |

| def as_mm(number): | |

| return repr(number) + "mm" | |

| parser = ArgumentParser() | |

| parser.add_argument('–layernum', type=int, default=0) | |

| parser.add_argument('–colors', type=int, default=16) | |

| parser.add_argument('–seed', type=int, default=1) | |

| parser.add_argument('–width', type=int, default=16) | |

| parser.add_argument('–height', type=int, default=16) | |

| parser.add_argument('–debug', default=False) | |

| args = parser.parse_args() | |

| PageSize = (round(8.5*INCH,3), round(11.0*INCH,3)) | |

| SheetCenter = (PageSize[X]/2,PageSize[X]/2) # symmetric on Y! | |

| SheetSize = (200,200) # overall sheet | |

| AlignOC = (180,180) # alignment pins in corners | |

| AlignOD = 5.0 # … pin diameter | |

| MatrixOA = (170,170) # outer limit of cell matrix | |

| CellCut = "black" # C00 Black | |

| SheetCut = "red" # C02 Red | |

| HeavyCut = "rgb(255,128,0)" # C05 Orange black mask paper is harder | |

| HeavyCellCut = "rgb(0,0,160)" # C09 Dark Blue ditto | |

| Tooling = "rgb(12,150,217)" # T2 Tool | |

| DefStroke = "0.2mm" | |

| DefFill = "none" | |

| ThisLayer = args.layernum # determines which cells get cut | |

| Layers = args.colors # black mask = 0, color n = not perforated | |

| SashWidth = 1.5 # between adjacent cells | |

| CellSize = ((MatrixOA[X] – (args.width – 1)*SashWidth)/args.width, | |

| (MatrixOA[Y] – (args.height – 1)*SashWidth)/args.height) | |

| CellOC = (CellSize[X] + SashWidth,CellSize[Y] + SashWidth) | |

| if args.seed: | |

| seed(args.seed) | |

| #— accumulate tooling layout | |

| ToolEls = [] | |

| # mark center of sheet for drag-n-drop location | |

| ToolEls.append( | |

| svg.Circle( | |

| cx=SheetCenter[X], | |

| cy=SheetCenter[Y], | |

| r="2mm", | |

| stroke=Tooling, | |

| stroke_width=DefStroke, | |

| fill="none", | |

| ) | |

| ) | |

| # mark page perimeter for alignment check | |

| if False: | |

| ToolEls.append( | |

| svg.Rect( | |

| x=0, | |

| y=0, | |

| width=as_mm(PageSize[X]), | |

| height=as_mm(PageSize[Y]), | |

| stroke=Tooling, | |

| stroke_width=DefStroke, | |

| fill="none", | |

| ) | |

| ) | |

| # center huge box on matrix center | |

| if False: | |

| ToolEls.append( | |

| svg.Rect( | |

| x=as_mm(SheetCenter[X] – 2*SheetSize[X]/2), | |

| y=as_mm(SheetCenter[Y] – 2*SheetSize[Y]/2), | |

| width=as_mm(2*SheetSize[X]), | |

| height=as_mm(2*SheetSize[Y]), | |

| stroke=Tooling, | |

| stroke_width=DefStroke, | |

| fill="none", | |

| ) | |

| ) | |

| #— accumulate sheet cuts | |

| SheetEls = [] | |

| # cut perimeter | |

| SheetEls.append( | |

| svg.Rect( | |

| x=as_mm(SheetCenter[X] – SheetSize[X]/2), | |

| y=as_mm(SheetCenter[Y] – SheetSize[Y]/2), | |

| width=as_mm(SheetSize[X]), | |

| height=as_mm(SheetSize[Y]), | |

| stroke=SheetCut if ThisLayer > 0 else HeavyCut, | |

| stroke_width=DefStroke, | |

| fill="none", | |

| ), | |

| ) | |

| # cut layer ID holes except on mask layer | |

| if ThisLayer > 0: | |

| c = ((1,1)) | |

| h = f'{ThisLayer:0{Layers.bit_length()}b}' | |

| for i in range(Layers.bit_length()): | |

| SheetEls.append( | |

| svg.Circle( | |

| cx=as_mm(SheetCenter[X] + c[X]*AlignOC[X]/2 – (i + 2)*AlignOD), | |

| cy=as_mm(SheetCenter[Y] + c[Y]*AlignOC[Y]/2), | |

| r=AlignOD/4 if h[-(i + 1)] == '1' else AlignOD/8, | |

| stroke=SheetCut, | |

| stroke_width=DefStroke, | |

| fill="none", | |

| ) | |

| ) | |

| # cut alignment pin holes except on mask layer | |

| if ThisLayer > 0: | |

| for c in ((1,1),(-1,1),(-1,-1),(1,-1)): | |

| SheetEls.append( | |

| svg.Circle( | |

| cx=as_mm(SheetCenter[X] + c[X]*AlignOC[X]/2), | |

| cy=as_mm(SheetCenter[Y] + c[Y]*AlignOC[Y]/2), | |

| r=as_mm(AlignOD/2), | |

| stroke=SheetCut, | |

| stroke_width=DefStroke, | |

| fill="none", | |

| ) | |

| ) | |

| #— calculate matrix contents | |

| CenterPoint = (choice(range(args.width)),choice(range(args.height))) | |

| CellMatrix = [[math.hypot(x – CenterPoint[X],y – CenterPoint[Y]) | |

| for y in range(args.height)] | |

| for x in range(args.width)] | |

| dmax = max(list(chain.from_iterable(CellMatrix))) | |

| if args.debug: | |

| print(CenterPoint) | |

| print(dmax) | |

| pprint(CellMatrix) | |

| print() | |

| #— accumulate matrix cuts | |

| LayerThreshold = (ThisLayer/Layers)*dmax | |

| if args.debug: | |

| print(LayerThreshold) | |

| MatrixEls = [] | |

| for i in range(args.width): | |

| x =i*CellOC[X] | |

| for j in range(args.height): | |

| y = j*CellOC[Y] | |

| if args.debug: | |

| print(i) | |

| print(j) | |

| print(CellMatrix[i][j]) | |

| if ThisLayer == 0: # black mask | |

| s = HeavyCellCut | |

| elif LayerThreshold < CellMatrix[i][j]: # rest of sheets above color layer | |

| s = CellCut | |

| else: | |

| s = Tooling # at or below color layer | |

| MatrixEls.append( | |

| svg.Rect( | |

| x=as_mm(SheetCenter[X] – MatrixOA[X]/2 + x), | |

| y=as_mm(SheetCenter[Y] – MatrixOA[Y]/2 + y), | |

| width=as_mm(CellSize[X]), | |

| height=as_mm(CellSize[Y]), | |

| stroke=s, | |

| stroke_width=DefStroke, | |

| fill="none", | |

| ) | |

| ) | |

| #— assemble and blurt out the SVG file | |

| if not args.debug: | |

| canvas = svg.SVG( | |

| width=as_mm(PageSize[X]), | |

| height=as_mm(PageSize[Y]), | |

| elements=[ | |

| ToolEls, | |

| SheetEls, | |

| MatrixEls | |

| ], | |

| ) | |

| print(canvas) |