The relatively low bandwidth of the amplified noise means two successive samples (measured in Arduino time) will be highly correlated. Rather than putz around with variable delays between the samples, I stuffed the noise directly into the Arduino’s MISO pin and collected four bytes of data while displaying a single row:

unsigned long UpdateLEDs(byte i) {

unsigned long NoiseData = 0ul;

NoiseData |= (unsigned long) SendRecSPI(~LEDs[i].ColB); // correct for low-active outputs

NoiseData |= ((unsigned long) SendRecSPI(~LEDs[i].ColG)) << 8;

NoiseData |= ((unsigned long) SendRecSPI(~LEDs[i].ColR)) << 16;

NoiseData |= ((unsigned long) SendRecSPI(~LEDs[i].Row)) << 24;

analogWrite(PIN_DIMMING,LEDS_OFF); // turn off LED to quench current

PulsePin(PIN_LATCH); // make new shift reg contents visible

analogWrite(PIN_DIMMING,LEDS_ON);

return NoiseData;

}

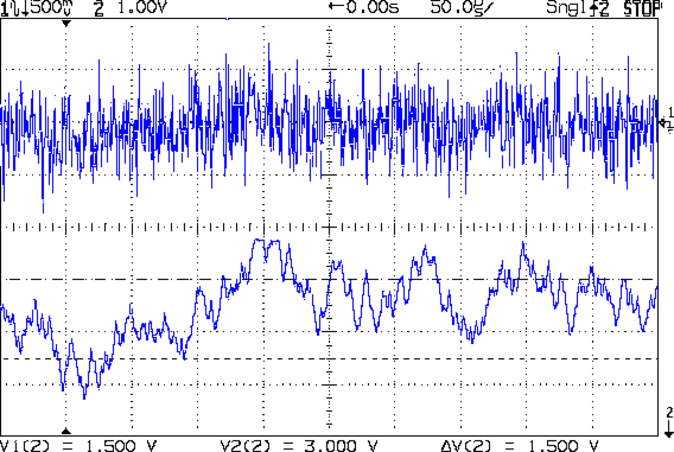

The bit timing looks like this:

The vertical cursors mark the LSB position in the first and last bytes of the SPI clock. The horizontal cursors mark the minimum VIH and maximum VIL, so the sampled noise should produce 0 and 1 bits at the vertical cursors. Note that there’s no shift register on the input: MISO just samples the noise signal at each rising clock edge.

I picked those two bit positions because they produce more-or-less equally spaced samples during successive rows; you can obviously tune the second bit position for best picture as you see fit.

Given a pair of sequential samples, a von Neumann extractor whitens the noise and returns at most one random bit:

#define VNMASK_A 0x00000001

#define VNMASK_B 0x01000000

enum sample_t {VN_00,VN_01,VN_10,VN_11};

typedef struct {

byte BitCount; // number of bits accumulated so far

unsigned Bits; // random bits filled from low order upward

int Bias; // tallies 00 and 11 sequences to measure analog offset

unsigned SampleCount[4]; // number of samples in each bin

} random_t;

random_t RandomData;

... snippage ...

byte ExtractRandomBit(unsigned long RawSample) {

byte RetVal;

switch (RawSample & (VNMASK_A | VNMASK_B)) {

case 0: // 00 - discard

RetVal = VN_00;

RandomData.Bias--;

break;

case VNMASK_A: // 10 - true

RetVal = VN_10;

RandomData.BitCount++;

RandomData.Bits = (RandomData.Bits << 1) | 1;

break;

case VNMASK_B: // 01 - false

RetVal = VN_01;

RandomData.BitCount++;

RandomData.Bits = RandomData.Bits << 1;

break;

case (VNMASK_A | VNMASK_B): // 11 - discard

RetVal = VN_11;

RandomData.Bias++;

break;

}

RandomData.Bias = constrain(RandomData.Bias,-9999,9999);

RandomData.SampleCount[RetVal]++;

RandomData.SampleCount[RetVal] = constrain(RandomData.SampleCount[RetVal],0,63999);

return RetVal;

}

The counters at the bottom track some useful statistics.

You could certainly use something more complex, along the lines of a hash function or CRC equation, to whiten the noise, although that would eat more bits every time.

The main loop blips a pin to show when the extractor discards a pair of identical bits, as in this 11 sequence:

That should happen about half the time, which it pretty much does:

The cursors mark the same voltages and times; note the slower sweep. The middle trace blips at the start of the Row 0 refresh.

On the average, the main loop collects half a random bit during each row refresh and four random bits during each complete array refresh. Eventually, RandomData.Bits will contain nine random bits, whereupon the main loop updates the color of a single LED, which, as before, won’t change 1/8 of the time.

The Arduino trundles around the main loop every 330 µs and refreshes the entire display every 2.6 ms = 375 Hz. Collecting nine random bits requires 9 x 330 µs = 3 ms, so the array changes slightly less often than every refresh. It won’t completely change every 64 x 8/7 x 3 ms = 220 ms, because dupes, but it’s way sparkly.

In the spirit of “Video or it didn’t happen!”, there’s a low-budget Youtube video about that…