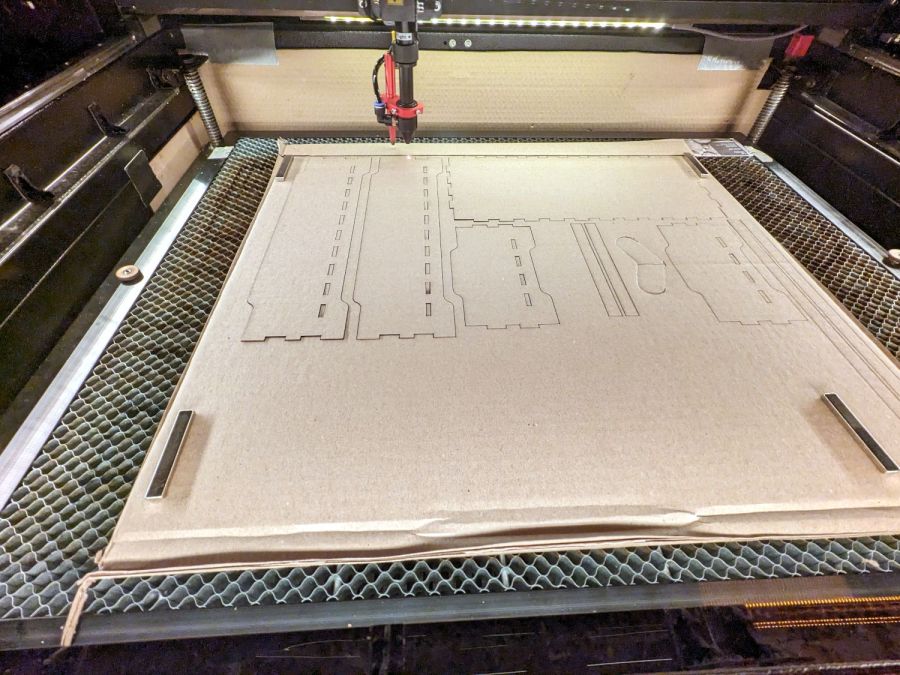

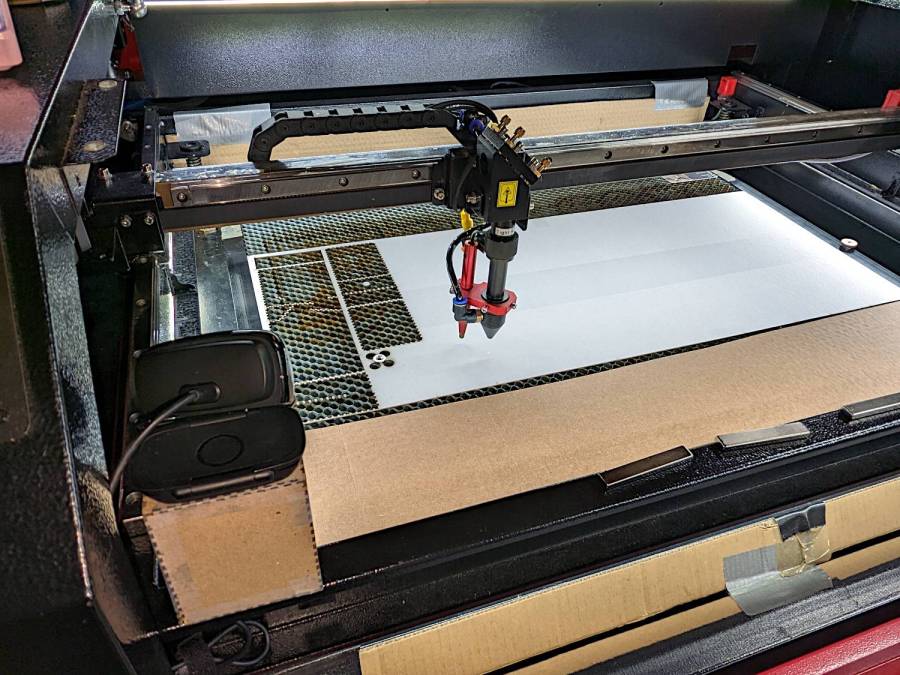

The pieces of a larger scrap bin ventured into the right-front quarter of the laser platform and didn’t cut well at all:

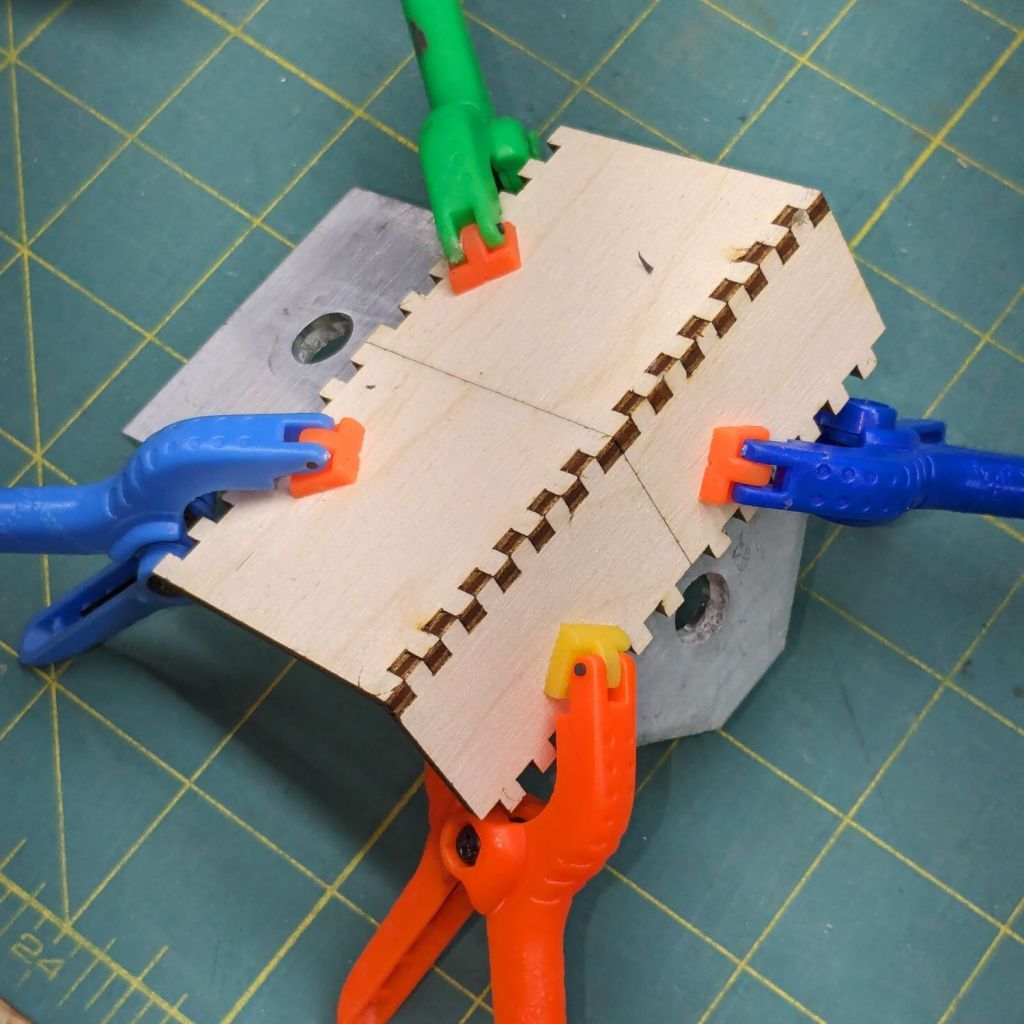

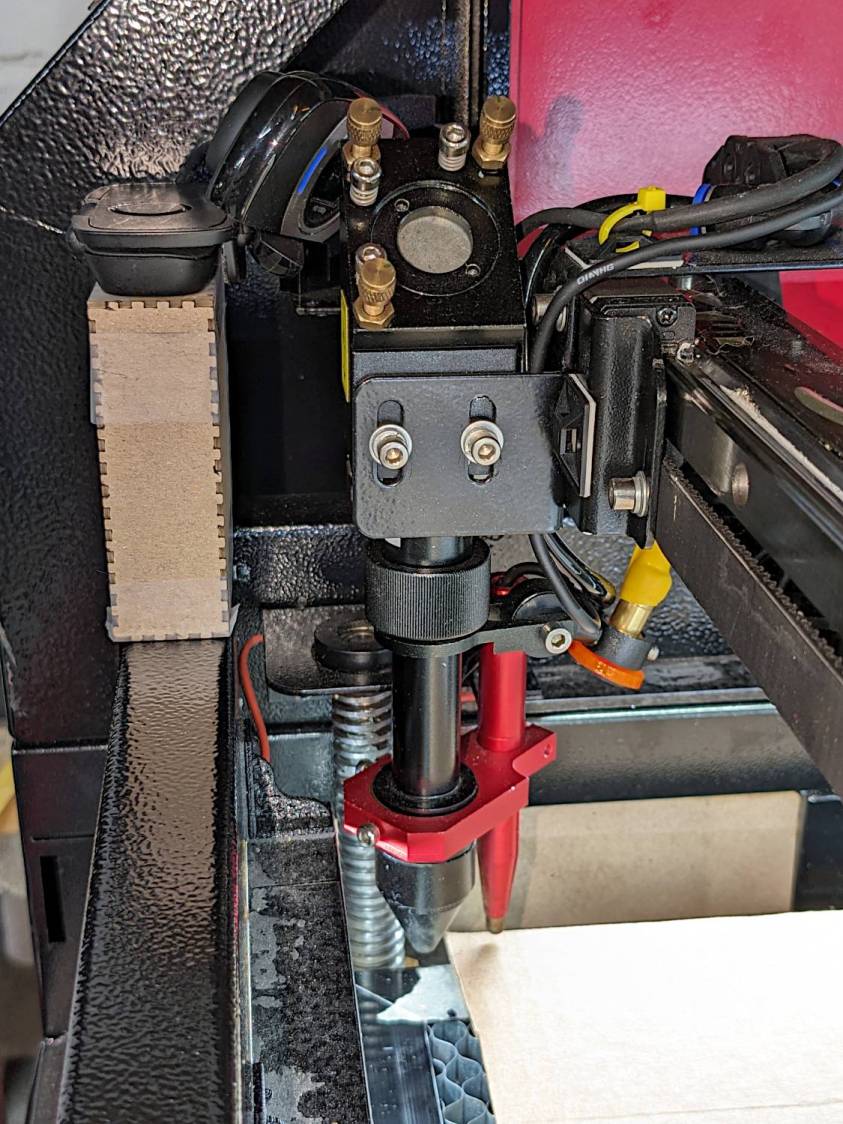

A closer look at the bottom right corner of that image shows the problem in more detail:

The intended cuts are the dark lines, each with a poorly defined scorch 2 mm on its left. Knowing that the nozzle is about 4 mm, this suggests the beam is off-center enough to juuuust kiss the nozzle and splash the outer part of the beam away.

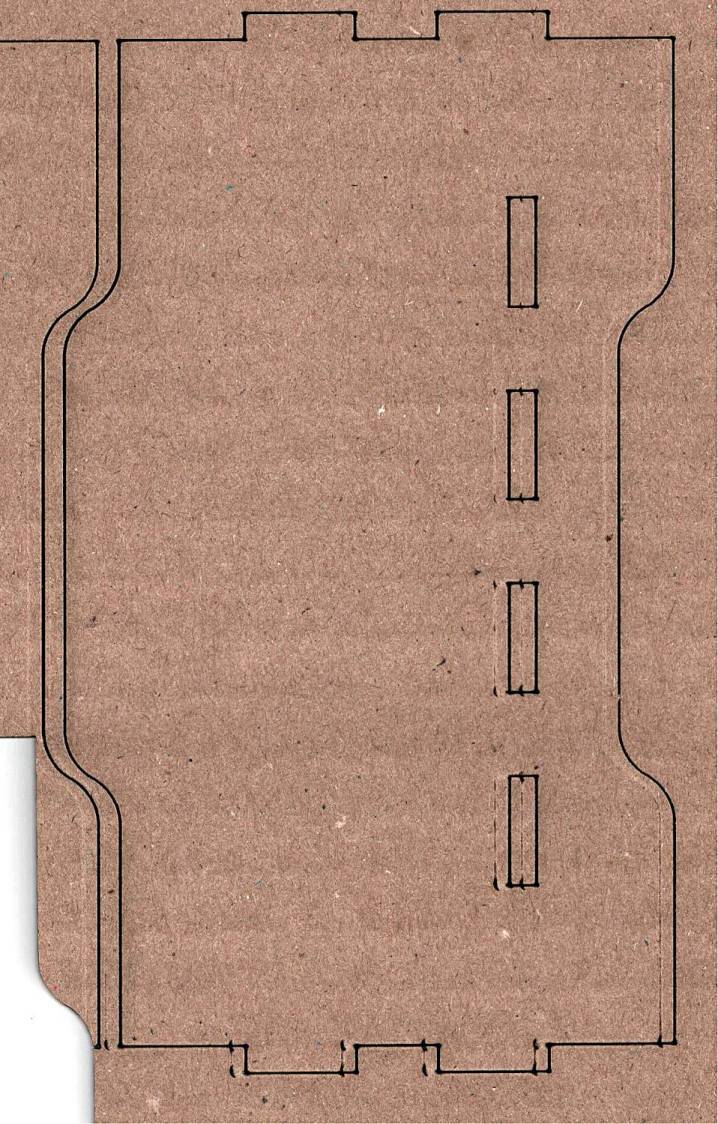

Having recently spot-checked the alignment and not seen any odd behavior on another platform-spanning project, this was puzzling. Given that the laser recently survived a move from one Basement Shop to another, with plenty of jostling while standing on end, I suppose I should have been more careful.

The biggest clue was seeing the shadow lines only near the front-right corner and noting they got worse farther into the corner. This seemed like the “fourth-corner” alignment problem described by St. Sadler some years ago and covered in a more succinct recent video.

AFAICT, the problem boils down to the difficulty of precisely aligning the beam at the longest distance it travels in the front-right corner. Careful adjustment of Mirror 1, after getting everything else lined up properly, seems to be solution.

The initial alignment at the first two mirrors looks OK, using targets taped parallel to the mirror plane:

The beam is slightly off-center at Mirror 1 and only a millimeter high on Mirror 2 at either end of the gantry travel along the Y axis.

The beam position at the laser head entry upstream of Mirror 3 shows the problem:

The targets are left- and right-rear, left- and right-front, with varying pulse lengths obviously underpowering the last and most distant shot.

Looks like a classic fourth-corner problem!

Tweaking Mirror 1 by about 1/8 turn of the adjusting screw to angle the beam vertically upward eventually put the beam dead-center at Mirror 3:

The bottom two targets are double pulses at the left- & right-rear and ‑front, so the beam is now well-centered.

A quick cross-check shows the beam remains centered on Mirror 2 at the front- and rear-end of the gantry travel, Mirror 3 is still OK, and the beam comes out of the center of the nozzle aperture:

Subsequent cutting proceeded perfectly all over the platform, so I think the alignment is now as good as it gets or, perhaps, as good as it needs to be.

Whew!