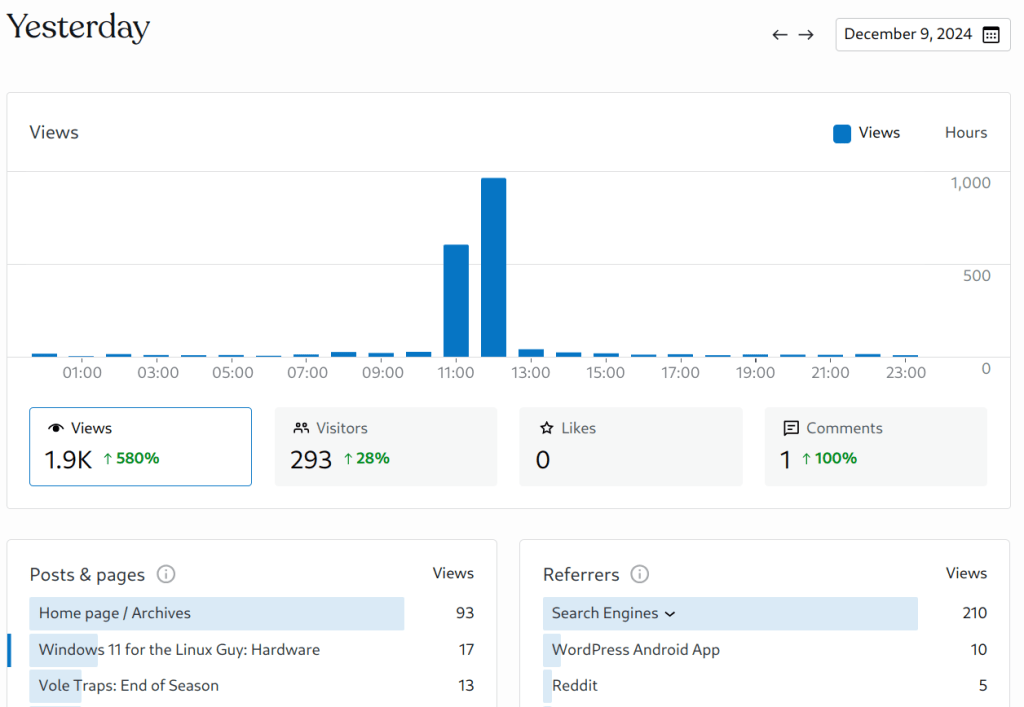

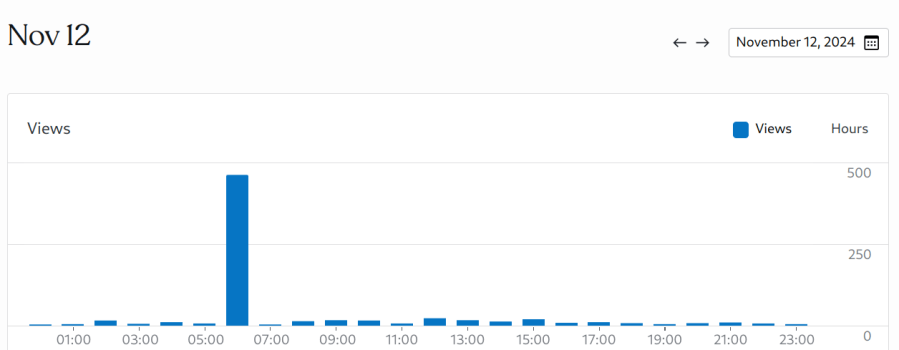

The kitchen came with matched Samsung appliances dating back to 2018 and, on a frigid winter day, we piled the contents of the freezer on the porch and gave it a deep cleaning. While the empty freezer was cooling down from its adventure, I wondered:

- Where were the condenser coils were located?

- Did they need cleaning?

- How does one do that?

The manual is strangely silent about even the existence of the coils, so evidently cleaning them wasn’t of any importance to Samsung.

Rolling the refrigerator away from the wall just enough to get the phone camera down there suggests they exist and are in need of some attention:

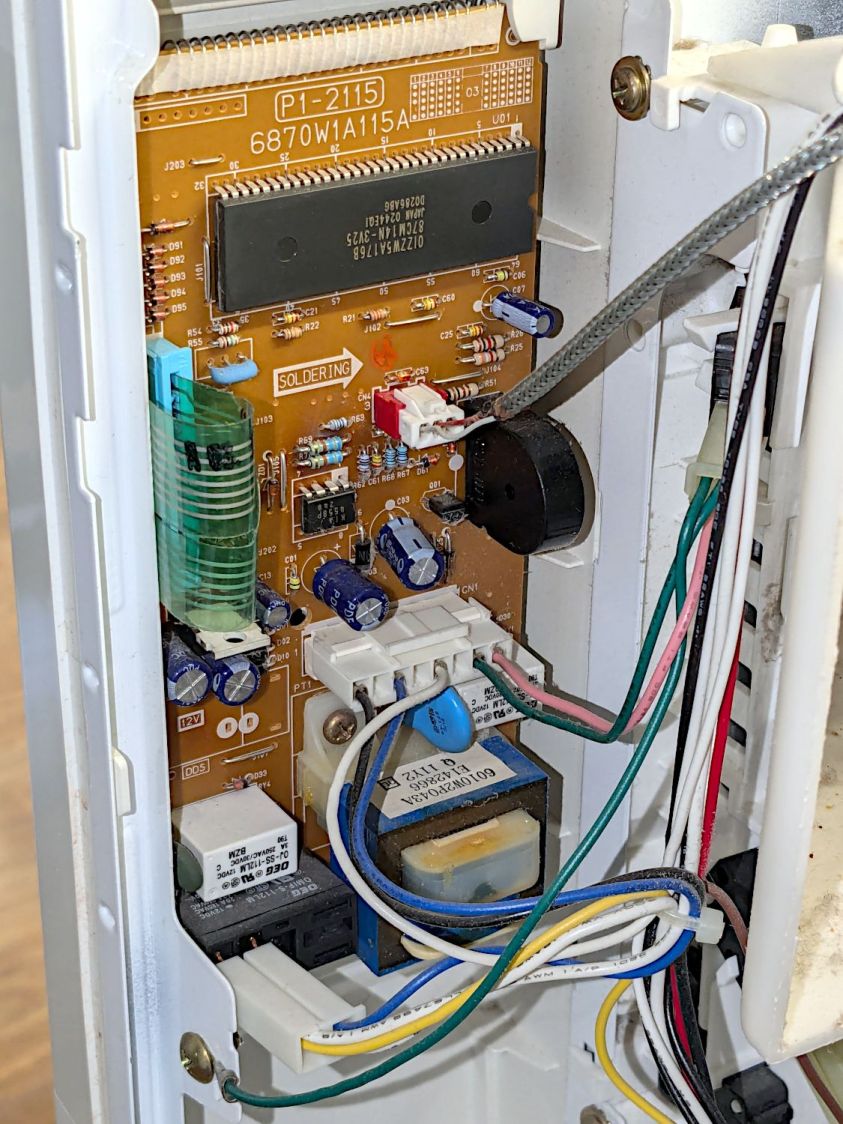

Rolling the refrigerator out until the door handles met the countertop across the way let me climb over the counter and worm myself into the refrigerator-sized hole behind it, bringing along a screwdriver, the vacuum cleaner snout, and a few brushes.

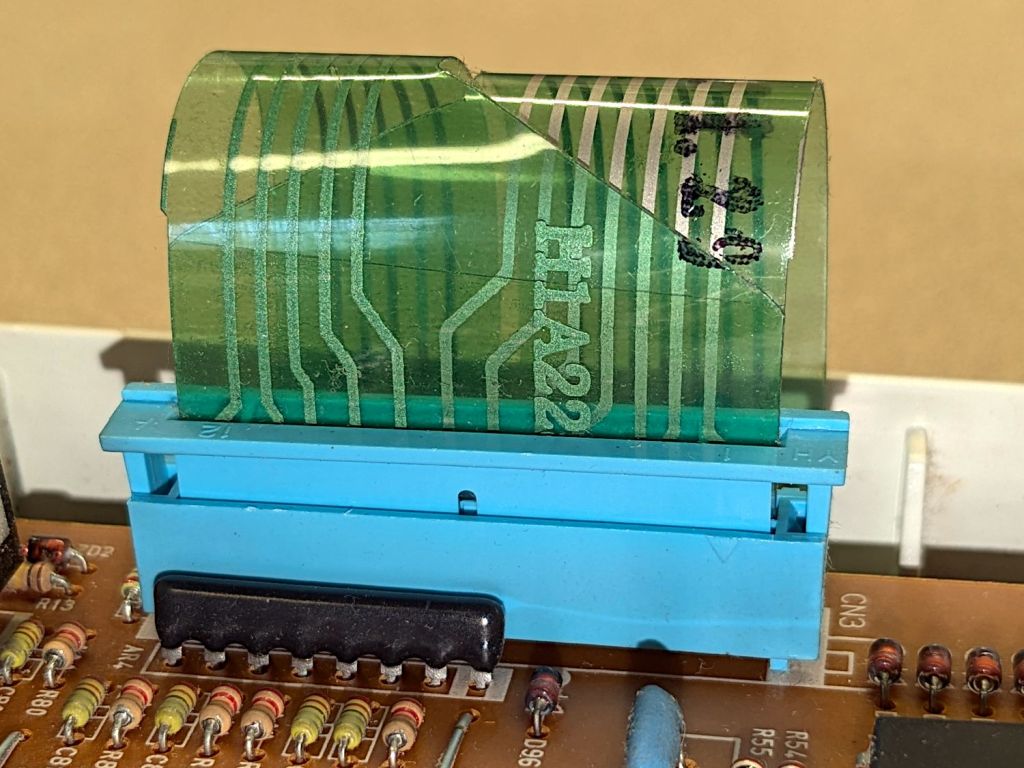

Removing five screws released the back cover:

Looking into the intake end of those coils (on the right):

So, yeah, I’m about to give them their first cleaning ever.

Five minutes of brushing fuzz, mostly into the vacuum, cleared a good bit of the exterior, but the interior needs more attention:

Ten minutes later:

Another five minutes:

Making the coils cleanable and putting them where they could be cleaned were obviously not bullet-item goals for Samsung’s designers.

Although the coils are not perfectly clean, I don’t know how to get them any cleaner, despite knowing even a thin layer of fuzz kills the refrigerator’s much-touted energy efficiency. Perhaps blowing them off with compressed air, then cleaning a thin layer of dust off the entire kitchen, would help.

I think the refrigerator will be happier, at least for a while.