Earlier this year, a pair of House Finches chose the a pine cone wreath hanging outside our front door for their nest.

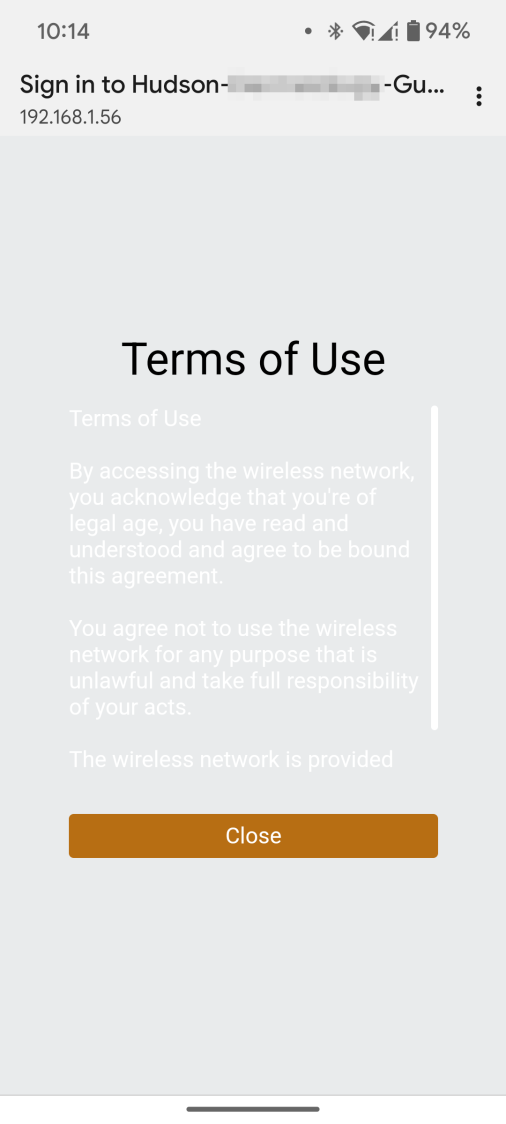

One day a Starling attacked:

There’s a Youtube video of the action following those pictures:

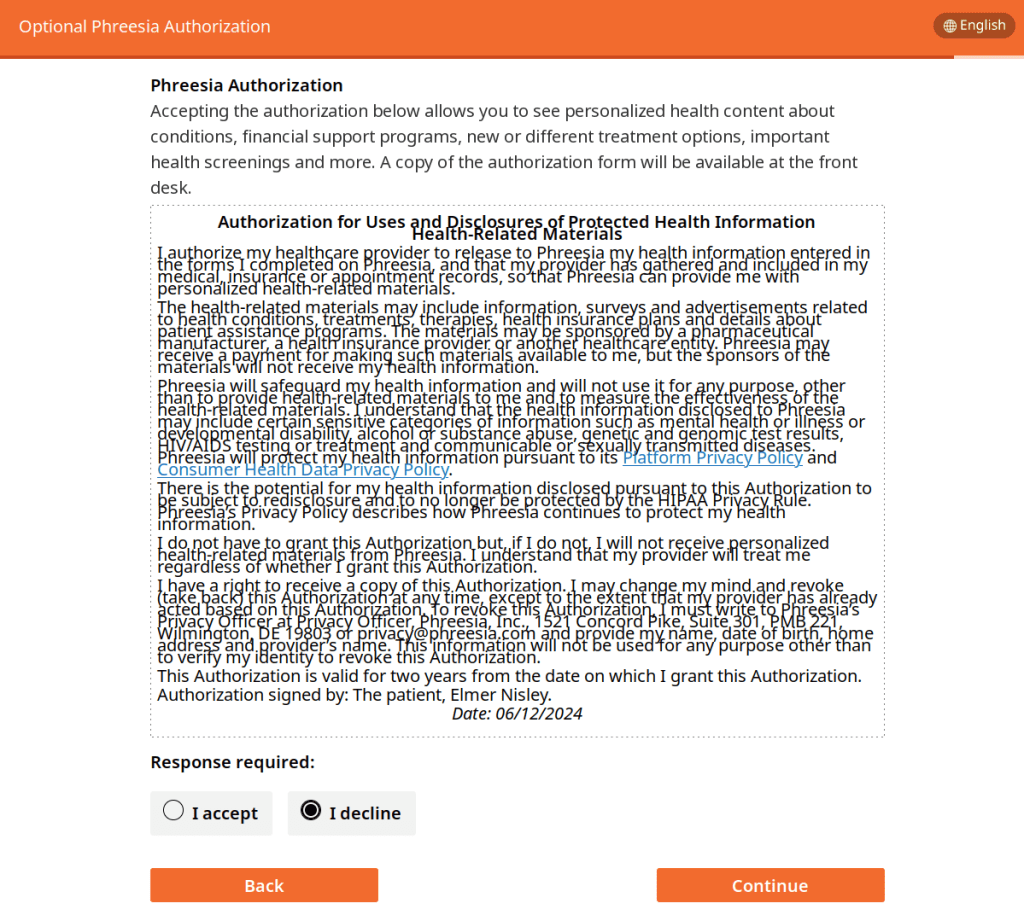

Ms. Finch suffered a peck to the head raising a few feathers into a small topknot, but seemed otherwise undamaged. The eggs survived unscathed and a month later they fledged a quartet of new finches:

Yes, they’re surrounded by a ring of bird crap: finch chicks can aim and fire overboard, but they don’t have much range.

The same finch pair abandoned their second nest after a Brown-headed Cowbird added an egg and punctured both Finch eggs:

Their third attempt failed after four eggs when a Cowbird added a fifth:

A few days after that picture, something tore that nest apart and destroyed all the eggs:

The scattered feathers suggest a major battle with severe injuries.

Three nesting attempts produced only four fledglings: a bad year for those two finches.