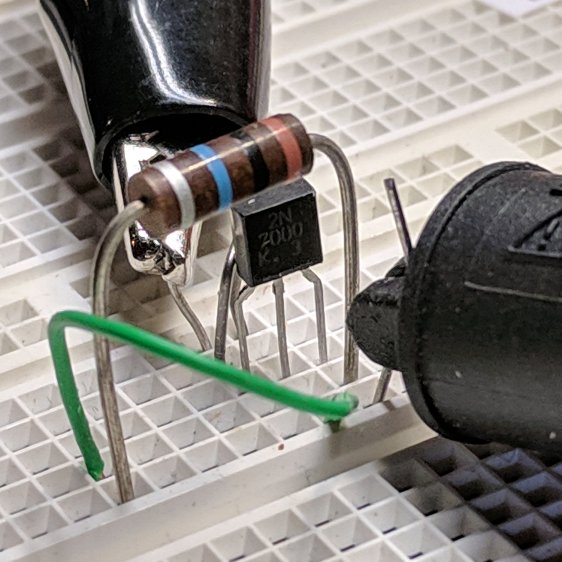

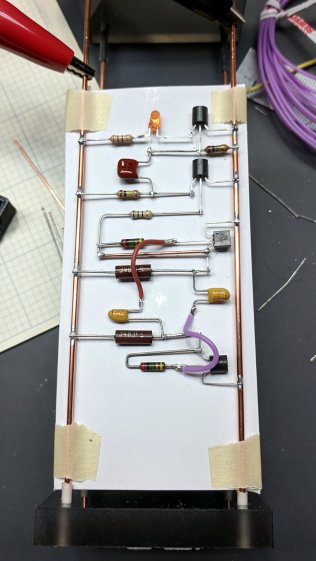

Taping a cardboard support under the soldering fixture helped hold all the parts in place:

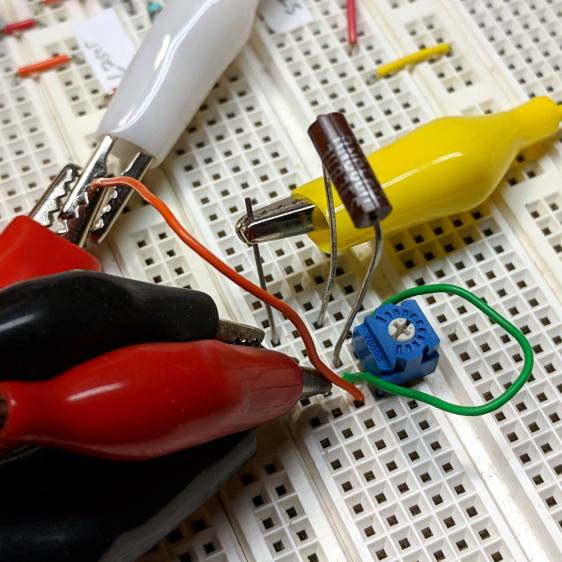

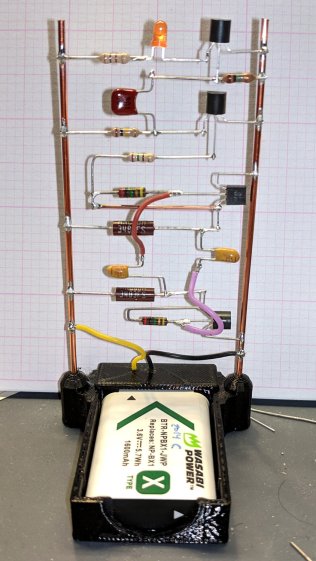

The struts fit neatly into an NP-BX1 battery holder and the circuit began blinking merrily:

My photography hand is weak …

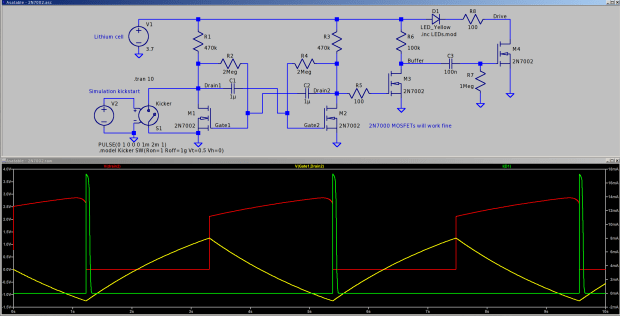

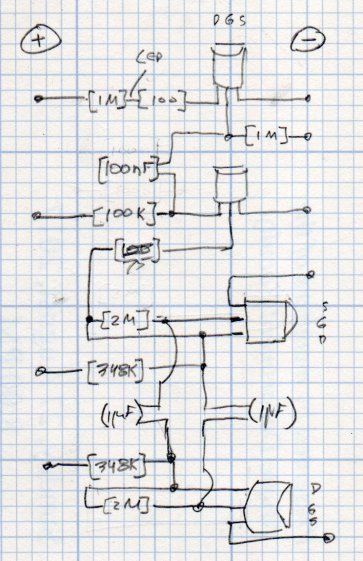

The circuit schematic / layout resembles this:

The missing 1 MΩ resistor at the LED would serve as a physical support to tether the loose end of the 100 (-ish) Ω resistor, which desperately needed some stabilization under the LED spider.

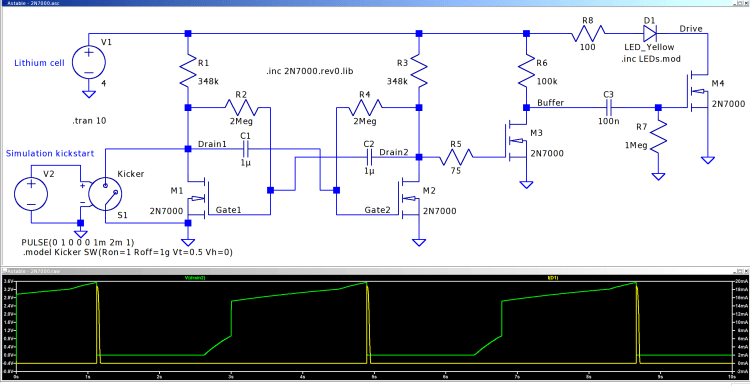

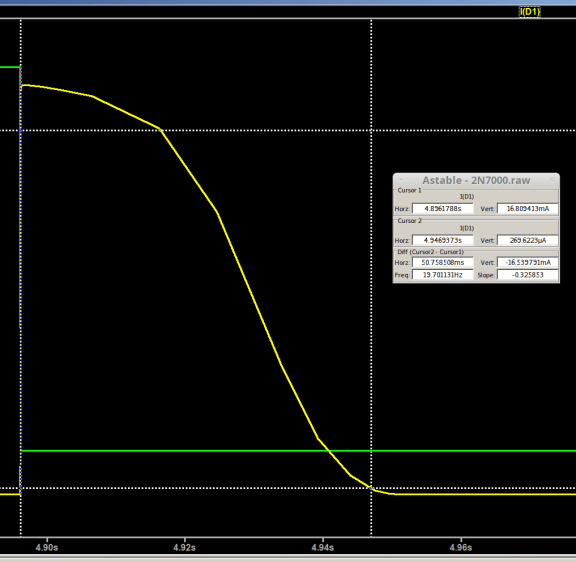

The simulation says it should blink about every 4s:

The 2N7000 MOSFETs use a SPICE model from the Motorola ON Semi downloads, although they behaved about the same way using the LTSpice 2N7002 model.

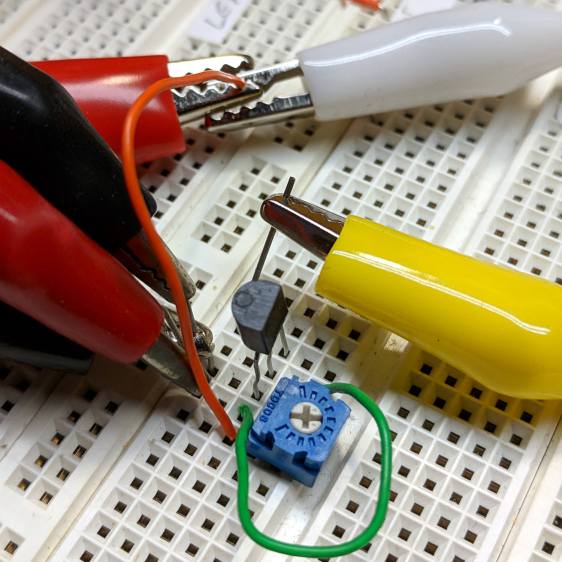

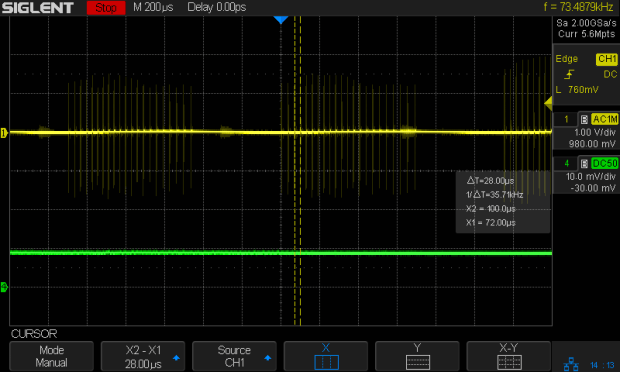

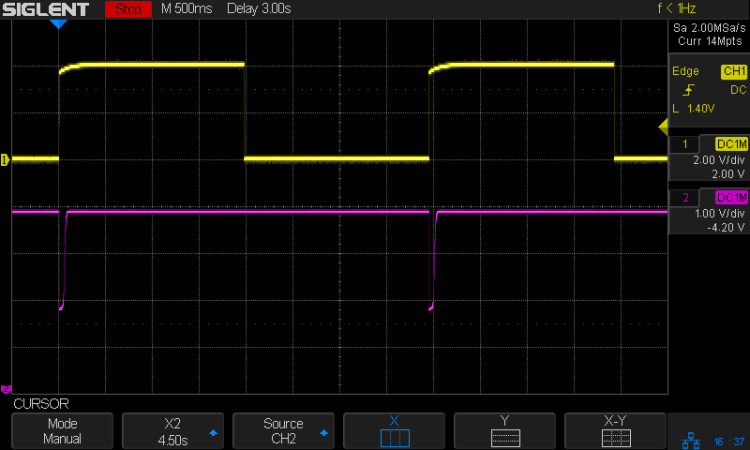

It really does blink every 4s:

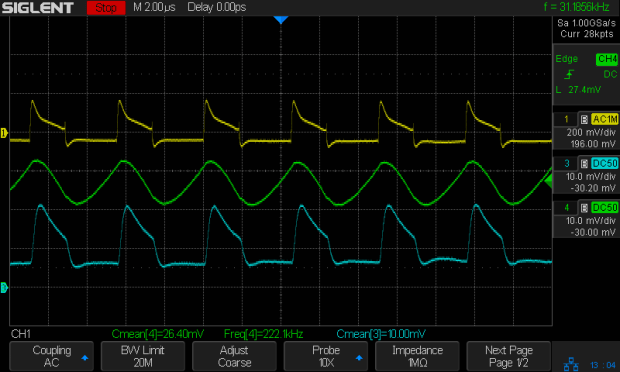

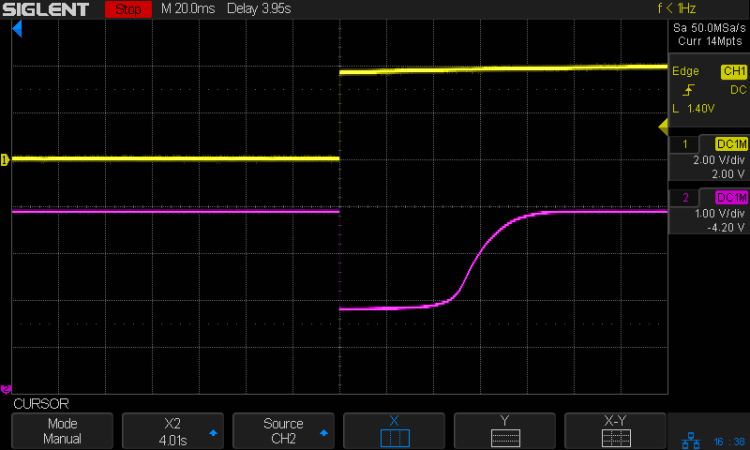

The LED pulse width should be about 50 ms:

The voltage at the bottom of the ballast resistor is directly proportional to the LED current:

So the pulse is actually 80-ish ms, which is Close Enough™ for my purposes.

The key advantage here is making both the astable’s period and the blink’s duration (roughly) proportional to the component values, so I can tweak them with some confidence the results will come out more-or-less right.

I love it when a plan comes together!