Adding two hard drive platters draws attention away from the printed puck holding the microcontroller:

Granted, it looks odd. I think it’s a step in the right direction, if there is any right direction at all.

The Smell of Molten Projects in the Morning

Ed Nisley's Blog: Shop notes, electronics, firmware, machinery, 3D printing, laser cuttery, and curiosities. Contents: 100% human thinking, 0% AI slop.

Electrical & Electronic gadgets

Adding two hard drive platters draws attention away from the printed puck holding the microcontroller:

Granted, it looks odd. I think it’s a step in the right direction, if there is any right direction at all.

With RF projects looming on the horizon, now seemed like a good time to restock the silver-mica capacitor supply:

That’s 150-ish little brown envelopes, found on eBay in the lowest-entropy state I can imagine, with about 11 pounds of caps delivered for a bit under $5/pound.

The envelopes bear date stamps from the mid- to late-60s:

I think these came directly from the Electro-Motive Mfg Co production line or QC lab, because some of the envelopes have notes about “WE”, “Bell Labs”, and suchlike. They seem to be special-production items, not the usual caps from your usual distributor.

The values and tolerances are weird beyond belief:

If you’re taking notes, 6160 pF lies halfway between the 6120 and 6190 values in the E192 series.

And, yes, that’s a cap with ½% tolerance (forgive the bright-red color imbalance):

Most of the caps are 1%, which is kinda-sorta typical for silver-mica. Then you find something unbelievable:

Stipulated, I’ve lived a sheltered existence. Have you ever seen a 0.1% tolerance cap? The assortment has more of those, scattered throughout the range.

Regrettably, the entire decade from just over 300 pF to just under 3000 pF has gone missing: somewhere out there, someone has another box from the room that housed this collection. So it goes; given the plethora of values, I can always make series-parallel combinations to get what’s needed.

While at another Vassar concert, I noticed a manufacturing date stamp on one of the LED exit signs in Skinner Hall:

I like the “Replacement lamp not applicable” line. I wonder how recently they’ve tested the battery for the projected 90 minutes of backup time…

These old LEDs show the expected brightness variations:

So, now you know what your discrete LEDs will look like after two decades of continuous use. That’s if anybody (else) still uses discrete LEDs, of course.

One of the Hobo dataloggers asked for a new battery during its most recent data dump. The old battery dates back to January 2015:

That was when a batch of Energizer cells failed in quick succession: it wasn’t the datalogger’s fault. I’ve been handling the cells a bit more carefully, too, although that certainly doesn’t account for the much longer life.

With batteries, particularly from eBay, you definitely can’t tell what you’re going to get or how long it’ll last; that’s true of many things in life.

A long time ago, I discovered some quasi-AAAA cells inside 9 V batteries:

It occurred to me that I should dismantle a defunct Rayovac Maximum 9 V alkaline battery from the most recent batch (*) to see what it looked like:

Surprise!

A closer look at those pancake cells:

They look like separate cells bonded into a stack, although there’s no easy way to probe the inter-cell contacts; the leftmost cell probably died first.

(*) Which has apparently outlived the Rayovac Maximum brand, as they don’t appear on the Rayovac site.

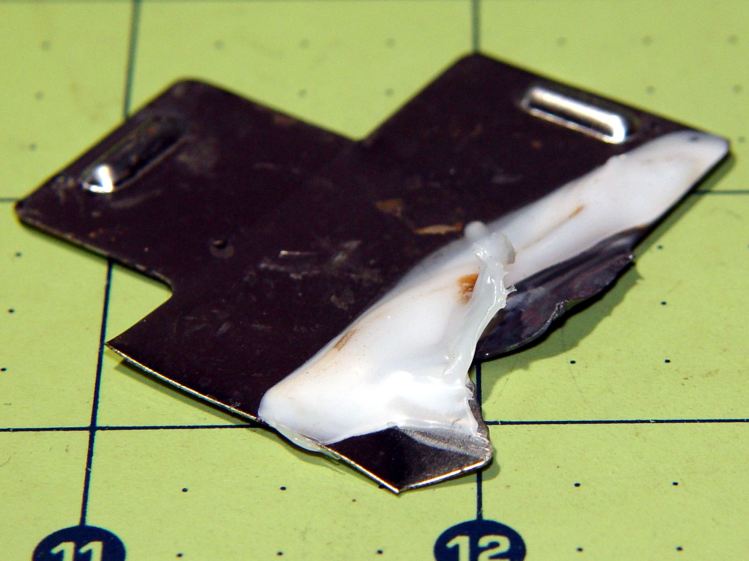

Sacrificing a scrap EMI shield from a junked PC as the electrolysis anode, I grabbed a tab with the battery charger clamp:

Turns out it didn’t survive the encounter:

That white blob extends around to the other side:

Yeah, it got hot enough to melt a blob from the 6 gallon plastic bucket before burning through.

I tossed that into the garage so I wouldn’t forget it aaaand here we are …

The single moving part on my first-generation (2011) Kindle Fire tablet stopped working: the power switch became erratic, to the point where the only dependable way to turn the thing on required the USB charging cable. Obviously not a long-term solution.

Having nothing to lose, I consulted the Internet’s vast steaming pile of advice on how to pop the Kindle’s cover, picked one, and ran with it. Basically, you jam a sharp tool into the end with the speakers, then crack the back off along both sides, leading to this:

Things to note:

Remove the six obvious screws, pull the battery edge of the board upward, and rotate the whole affair out of the chassis:

Protip: the power switch is not mounted on the tiny PCB (under the ribbon cable with the blue tab) sometimes advertised as the Power Button Board. That tiny PCB suspends an amber/green LED behind the visible button, but a yoke surrounds the LED to transfer the button motion to the power switch soldered to the CPU board. Replacing that board will not cure an erratic power switch; I think the entire CPU board is the FRU.

Fortunately, I can actually see the power switch and know sorta-kinda what to expect.

A bit of awkward multimeter probing showed the switch was defunct, with intermittent action and generally high resistance when pressed. I unsoldered the switch, verified that it didn’t work in isolation, and examined some likely candidates from the Big Box o’ Small Switches:

Some could be made to fit and maybe actually function, with effort ranging from tedious to Really Hard.

Then it occurred to me that maybe, just maybe, I could refurbish / clean / repair the Kindle’s switch contacts. Shaving off the two heat-staked plastic bumps on the front and prying the side latches outward produced an explosion of small parts:

That’s after cleaning the expected grunge from the three contact strips in the body and the innermost of the two (!) buckling-spring contact doodads (bottom left). I scrubbed with the cardboard-ish stem of a cotton swab and, as always, a dot of DeoxIT Red, inserted the unused-and-pristine contact spring doodad (bottom right) first, and reassembled the switch in reverse order.

The metal shell around the body has two locating tabs that fit in two PCB holes, giving the switch positive alignment and good strain relief. The front view shows the three human-scale components amid a sea of 0201 SMD parts:

For completeness, the view from the battery side:

It’s worth noting that you can see right through the 3.5 mm headphone jack, which accounts for the remarkable amount of dust & fuzz I blew out of the chassis. The overall dust sealing isn’t great, but after five years of life in my pocket, I suppose that’s to be expected.

Installing the board requires holding all the cables out of the way (tape the antenna & speaker wires to the battery), aiming the USB connector into its cutout, rotating the battery edge of the board downward, pushing the mesh EMI shield along the battery upward to clear the board edge, not forcing anything, and eventually it slides into place.

Insert cables, latch latches, plug in the battery, snap the rear cover in place, and It Just Works again. The power switch responds to a light touch with complete reliability; it hasn’t worked this well in a year.

Bonus: To my utter & complete astonishment, disconnecting the battery for few hours had no effect on the stored data: it powered up just fine with all the usual settings in place. I expected most of the settings to live in the Flash file system, but apparently nothing permanent lives in RAM.

Take that, entropy!