Pondering the Reversal Zittage Bestiary led me to wonder about the formal relationship between pressure and flow in a viscous fluid passing through a nozzle. I’ll cheerfully admit my never-very-puissant fluid dynamics fu has become way rusty and, this being the first time I’ve collected all this stuff in one place, there’s certainly something I’m overlooking (to put it charitably), but here goes…

Assuming that (semi-)molten plastic:

- Is an incompressible and highly viscous fluid, which means a very low Reynold’s Number

- Obeys Testicle’s Deviant (pronounced tes-tuh-cleez) to Fudd’s First Law of Opposition: What goes in must come out, unless it stays there

Counterargument:

The hot end contains about 20 mm of molten filament, which is 140 mm3 of 3 mm filament. During filament swaps, the filament pushes back about 2 mm = 14 mm3 without any external force, so there’s about 10% springiness in the hot end. That suggests the plastic really isn’t incompressible. Some of the springiness may come from the PTFE tube expanding against the surrounding metal tube, but the fact that the (solidified) molten zone has a larger diameter than the rest of the filament says the PTFE expansion is not very dynamic: the filament solidified at zero pressure.

Boldly assuming incompressiblity anyway, the always-right-and-never-lies Wikipedia tells us that the equations of state boil down to the Stokes Equations, herewith directly cribbed:

That’s using this symbology, typographically modified to eliminate the need for embedded graphics:

- The del operator represents the spatial gradient

- ∇p = pressure gradient

- u = fluid velocity

- ∇·u = divergence of velocity (pointiness)

- ∇2 u = Laplacian of velocity (sharpness of pointiness)

- μ = dynamic viscosity

- f = applied force

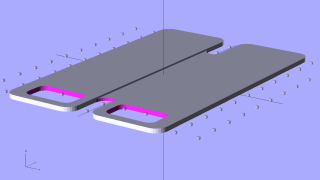

Under the breathtakingly aggressive simplifying assumption that we can model slices across the extruder’s nozzle as nearly 2D radially symmetric pipes with a teeny frustum shape, we have a mostly one-dimensional situation:

- The first equation says that axial pressure gradient is directly proportional to the applied force, which makes sense, plus a huge term due to the nozzle shape (how abruptly the velocity gradient changes)

- The second equation is a generalization of GladOS‘s explanation of the conservation of momentum across Portal transfers: Speedy thing goes in, speedy thing comes out. For slightly conical slices, the axial speed increases as the radial area decreases, but the overall velocity gradient comes out zero.

All the force f comes from a stepper motor ramming filament into the hot end:

- To a good first order approximation, stepper motor torque is proportional to winding current.

- For a given filament diameter, drive wheel diameter, and speed, a constant-current stepper applies constant force to the filament.

- Stepper power being roughly constant for a given current, the available force varies inversely with rotational speed.

Vigorous handwaving

The low Reynolds number says the inertial forces don’t amount to squat, so everything depends on viscous flow. There’s nothing to accelerate; try accelerating a spoon through honey.

Given a desired velocity u (mostly axial, for a particular extruding speed) and a nozzle, the first equation says the required force varies linearly with the pressure gradient ∇p. The gradient runs from atmospheric pressure on one end to the molten pool on the other, with the steepest change in the narrowest part of the nozzle. This suggests a short nozzle aperture is good.

Conversely, a long smooth nozzle reduces ∇2 u by reducing abrupt velocity changes. For a given ∇p, the required force varies directly with the second (spatial) derivative of the velocity; lower velocity doesn’t mean lower force, but smoother changes (and their derivatives) certainly do.

During reversal, the extruder must produce a negative ∇p very quickly to inhale the filament and prevent drooling. Assuming ∇p has the same order of magnitude in both directions (thus, different signs), changing the fluid velocity will produce huge changes in ∇2 u.

Fluid compressibility means that, during the early part of the reversal operation, moving the filament doesn’t change the pressure by very much at all: the first equation remains pretty much constant.

Caveats

The Stokes equations are time-invariant: the velocity is a constant. So we’re looking at the steady state and making dangerous assumptions about changing conditions.

The force variation seems linear with pressure gradient around a given flow, which is comforting: at least it’s not quadratic or something even more horrible.

Given the low Reynolds number, even moderate flow variations should be roughly linear, as the velocity gradients won’t change much with changing velocity.

This explains why Reversal Zittage gets so much worse at higher speeds: the extruder operates under constant (and, at least in my TOM, low) power that can keep pace with normal extrusion, but doesn’t have an order of magnitude more force in reserve for retraction.