Although it’s common practice to exchange your empty 20 pound propane tank for a full one, I vastly prefer to keep my own tanks: I know where they’ve been, how they’ve been used, and can be reasonably sure they don’t have hidden damage. Two of my tanks have old-style threaded connections, but the barby has a quick-disconnect fitting on the regulator and I’ve been using an adapter on those tanks.

The adapter comes with a plastic tool that you use to install it in the tank valve. In principle, you insert the tool into the adapter, thread the adapter into the valve, then tighten with a wrench until the neck of the plastic tool snaps, at which point you eject the stub and the adapter becomes permanently installed. I don’t like permanent, so I carefully tightened the adapter to the point where the O-ring seals properly and the tool didn’t quite break. I’ve always wanted a backup tool, just in case the original broke, and now I have one:

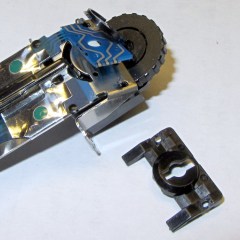

It fit into both the adapter body and the 5/8 inch wrench (the OEM tool is 9/16 inch) without any fuss at all:

The solid model has a few improvements over the as-printed tool above:

- Shorter wrench flats

- More durable protrusions to engage the locking balls

It took about an hour to design and another 45 minutes to print, so it’s obviously not cost-effective. I’ll likely never print another, but maybe you will.

The OpenSCAD source code:

// Propane tank QD connector adapter tool

// Ed Nisley KE4ZNU November 2012

include </mnt/bulkdata/Project Files/Thing-O-Matic/MCAD/units.scad>

include </mnt/bulkdata/Project Files/Thing-O-Matic/Useful Sizes.scad>

//- Extrusion parameters must match reality!

// Print with +1 shells and 3 solid layers

ThreadThick = 0.25;

ThreadWidth = 2.0 * ThreadThick;

HoleWindage = 0.2;

function IntegerMultiple(Size,Unit) = Unit * ceil(Size / Unit);

Protrusion = 0.1; // make holes end cleanly

//----------------------

// Dimensions

WrenchSize = (5/8) * inch; // across the flats

WrenchThick = 10;

NoseDia = 8.6;

NoseLength = 9.0;

LockDia = 12.5;

LockRingLength = 1.0;

LockTaperLength = 1.5;

TriDia = 15.1;

TriWide = 12.2; // from OD across center to triangle side

TriOffset = TriWide - TriDia/2; // from center to triangle side

TriLength = 9.8;

NeckDia = TriDia;

NeckLength = 4.0;

//----------------------

// Useful routines

module PolyCyl(Dia,Height,ForceSides=0) { // based on nophead's polyholes

Sides = (ForceSides != 0) ? ForceSides : (ceil(Dia) + 2);

FixDia = Dia / cos(180/Sides);

cylinder(r=(FixDia + HoleWindage)/2,

h=Height,

$fn=Sides);

}

module ShowPegGrid(Space = 10.0,Size = 1.0) {

Range = floor(50 / Space);

for (x=[-Range:Range])

for (y=[-Range:Range])

translate([x*Space,y*Space,Size/2])

%cube(Size,center=true);

}

//-------------------

// Build it...

$fn = 4*6;

ShowPegGrid();

union() {

translate([0,0,(WrenchThick + NeckLength + TriLength - LockTaperLength - LockRingLength + Protrusion)])

cylinder(r1=NoseDia/2,r2=LockDia/2,h=LockTaperLength);

translate([0,0,(WrenchThick + NeckLength + TriLength - LockRingLength)])

cylinder(r=LockDia/2,h=LockRingLength);

difference() {

union() {

translate([0,0,WrenchThick/2])

cube([WrenchSize,WrenchSize,WrenchThick],center=true);

cylinder(r=TriDia/2,h=(WrenchThick + NeckLength +TriLength));

cylinder(r=NoseDia/2,h=(WrenchThick + NeckLength + TriLength + NoseLength));

}

for (a=[-1:1]) {

rotate(a*120)

translate([(TriOffset + WrenchSize/2),0,(WrenchThick + NeckLength + TriLength/2 + Protrusion/2)])

cube([WrenchSize,WrenchSize,(TriLength + Protrusion)],center=true);

}

}

}