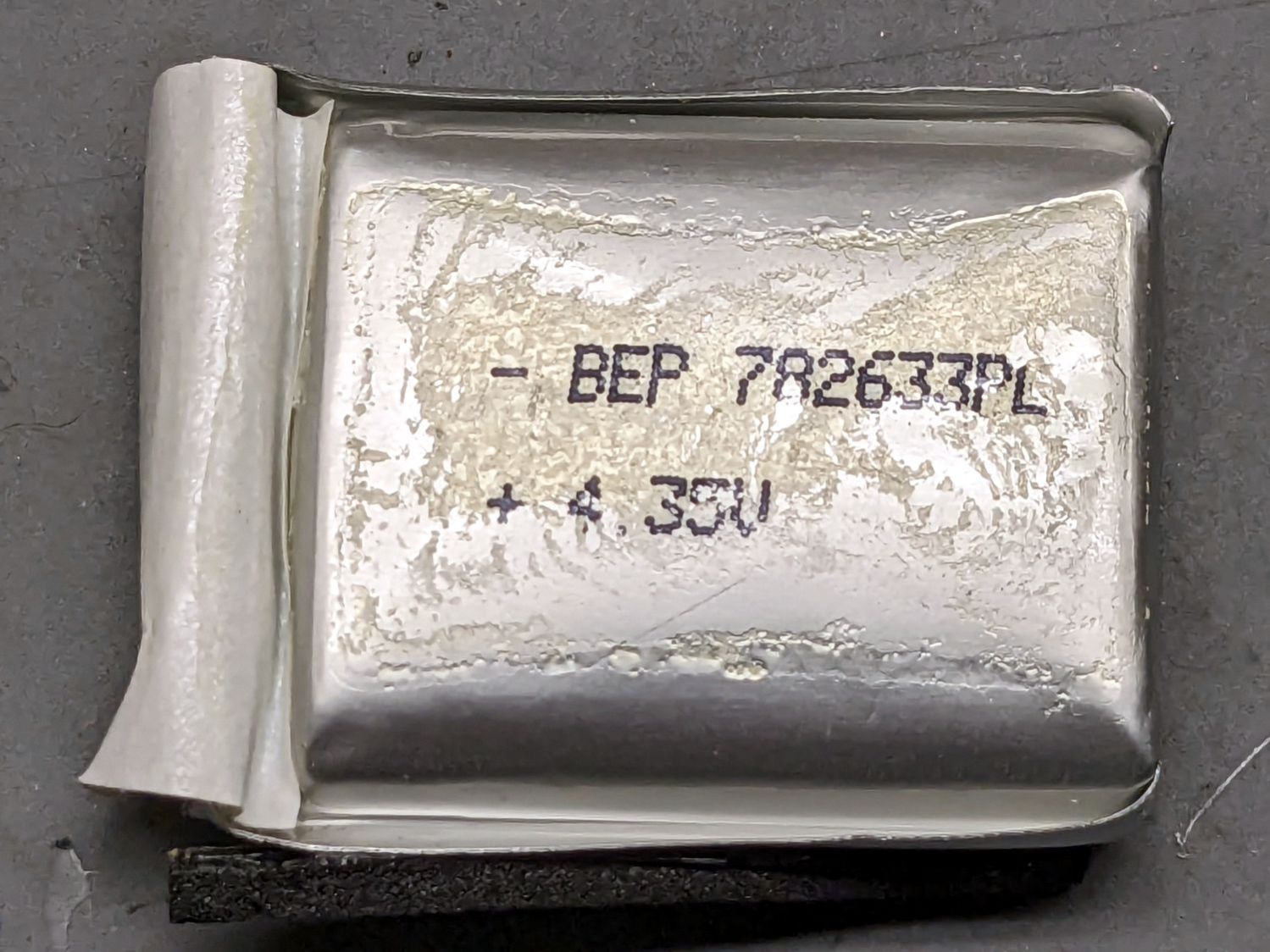

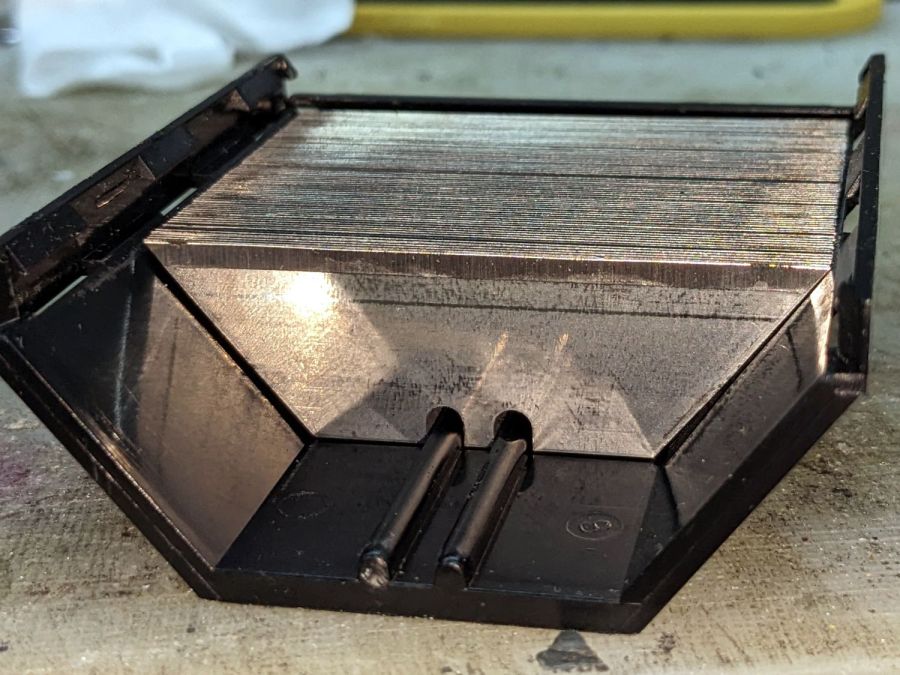

A little tweakage to the NP-BX1 battery holder for the astable multivibrator blinkies produced a simple version with the wire exit holes on the bottom:

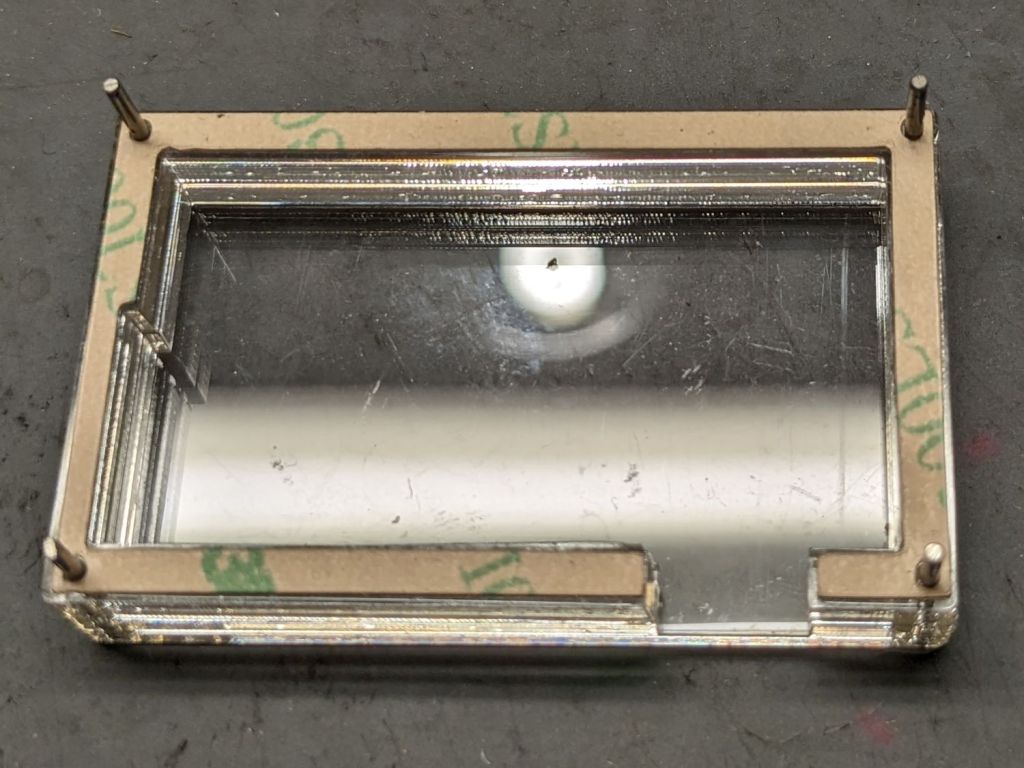

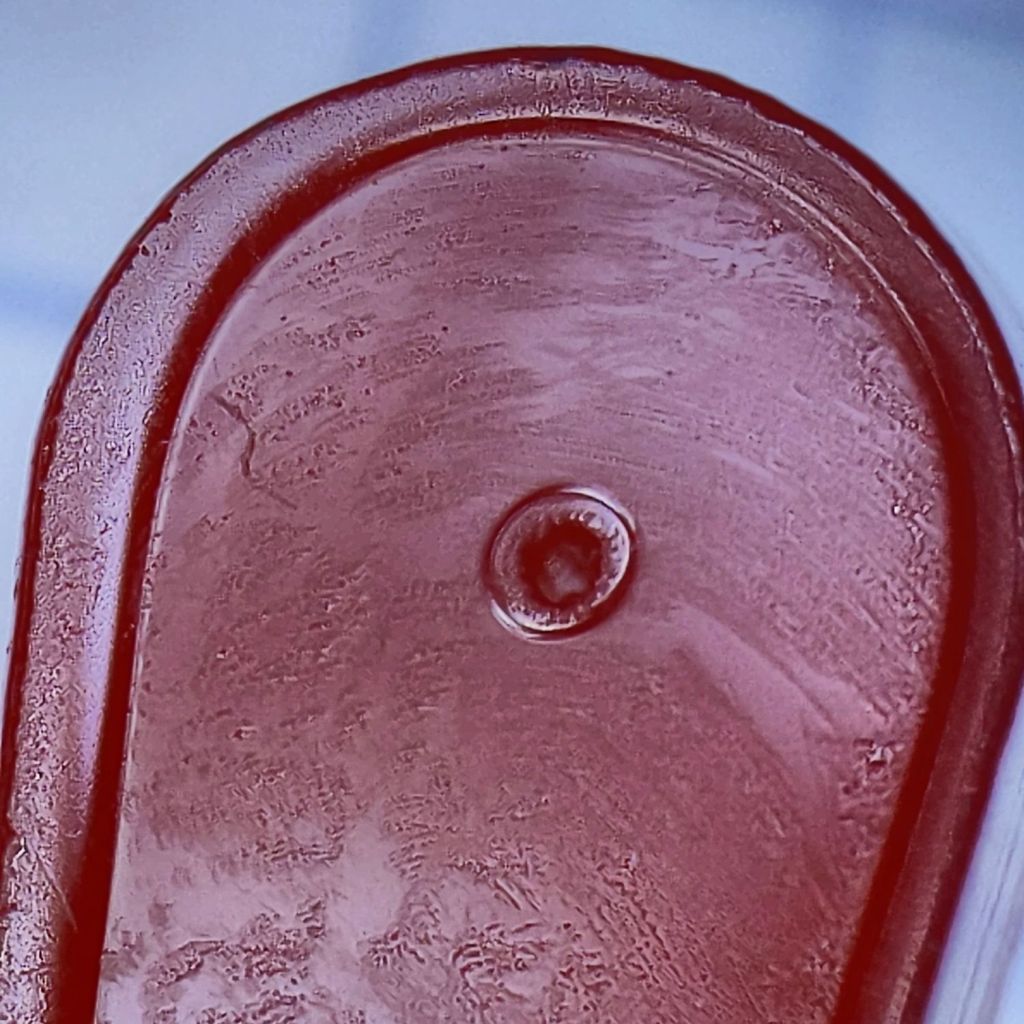

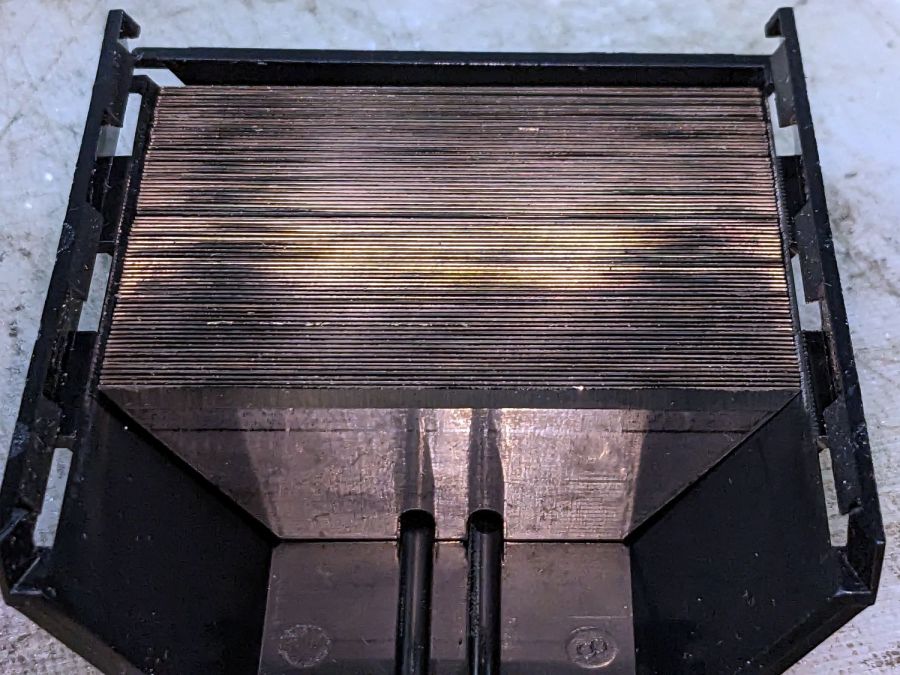

The four corner holes hold locating pins in the layered acrylic base:

Those pins got cut slightly shorter to fit in the battery holder; in this photo they’re serving to align the layers and adhesive sheets while I stacked them up.

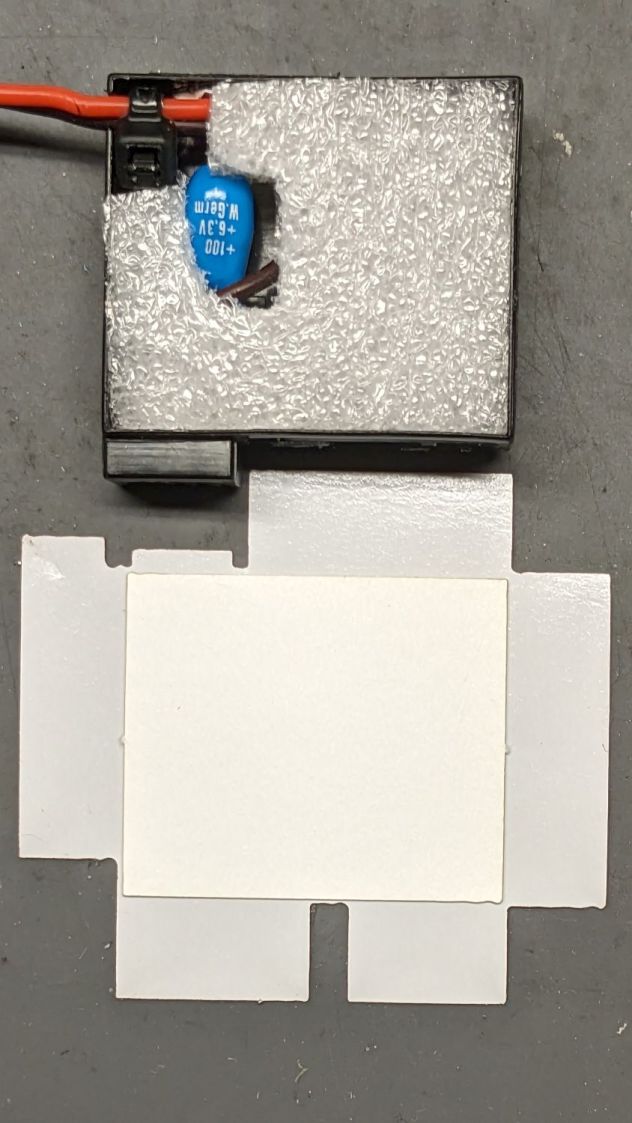

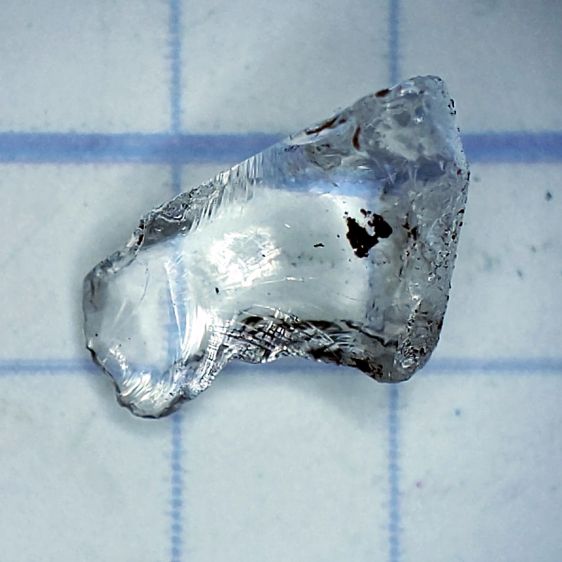

The geometry is straightforward, with the outer perimeter matching the 3D printed battery holder:

Cut one base and two wall layers from 3 mm (or a bit less) transparent acrylic, plus three adhesive sheets. I stuck adhesive on both sides of one wall layer, using the pins to align the adhesive, stuck the layer to the base, then topped it with the second wall layer, again using the alignment pins.

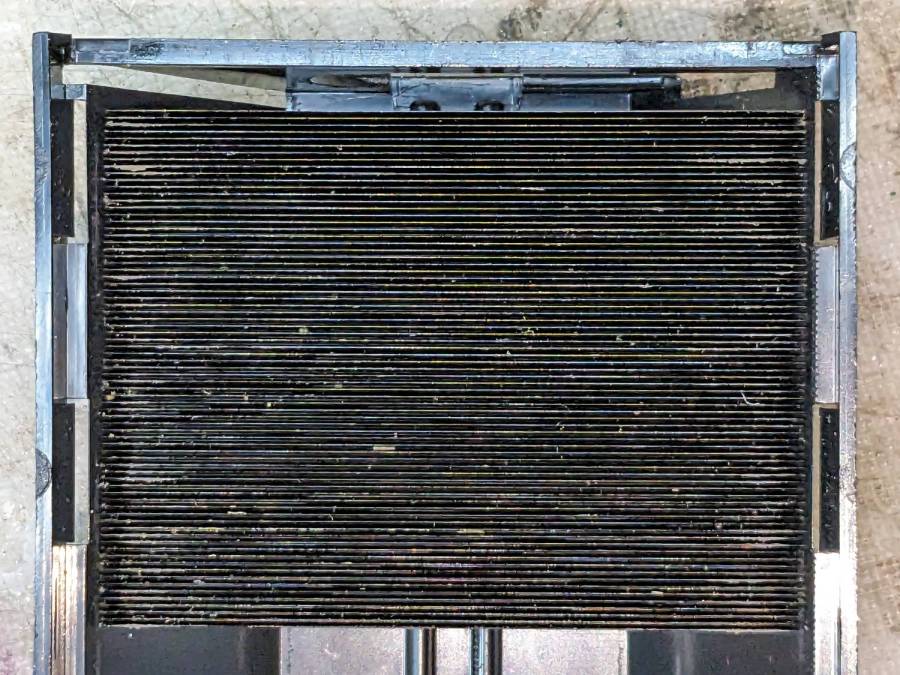

The motivation for transparent layered acrylic is being able to see the charge controller’s red and green status LEDs glowing inside the box. This probably isn’t required, but seemed like a Good Idea™ for the initial version.

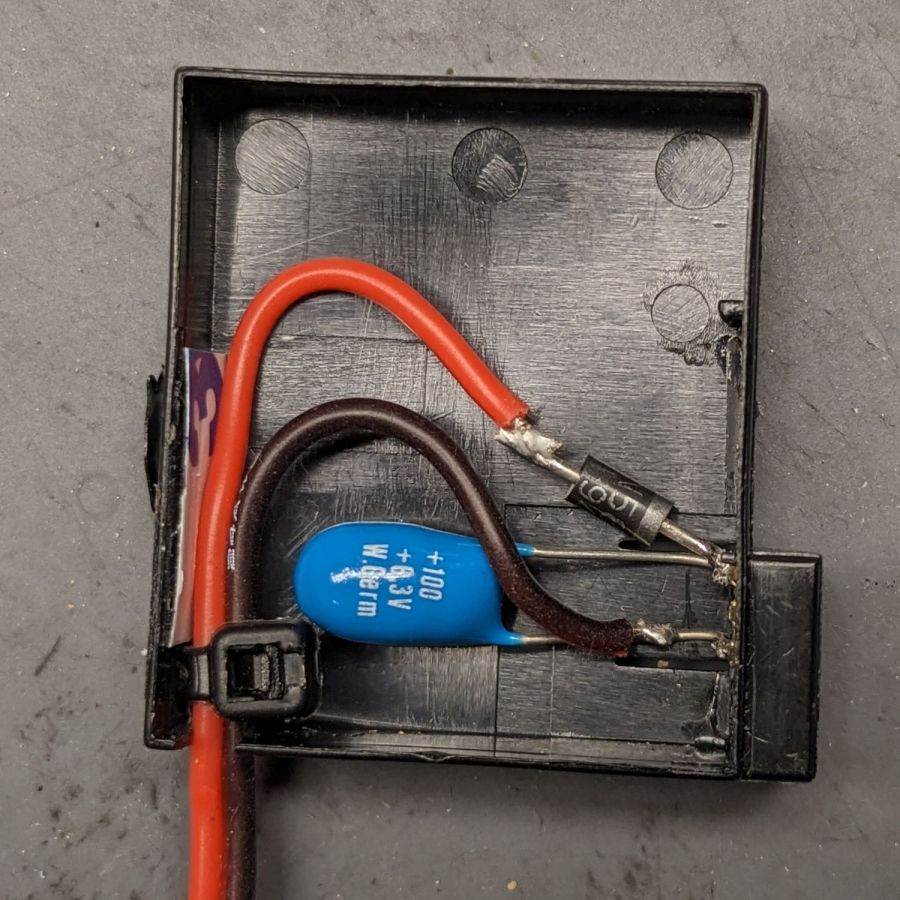

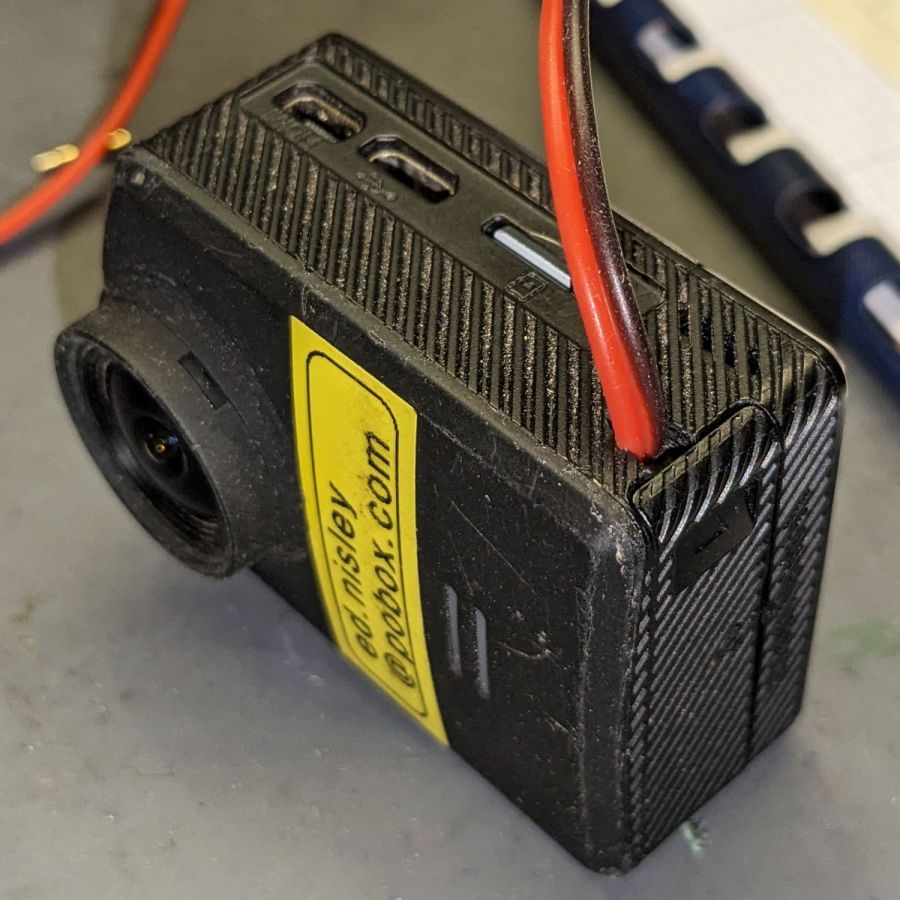

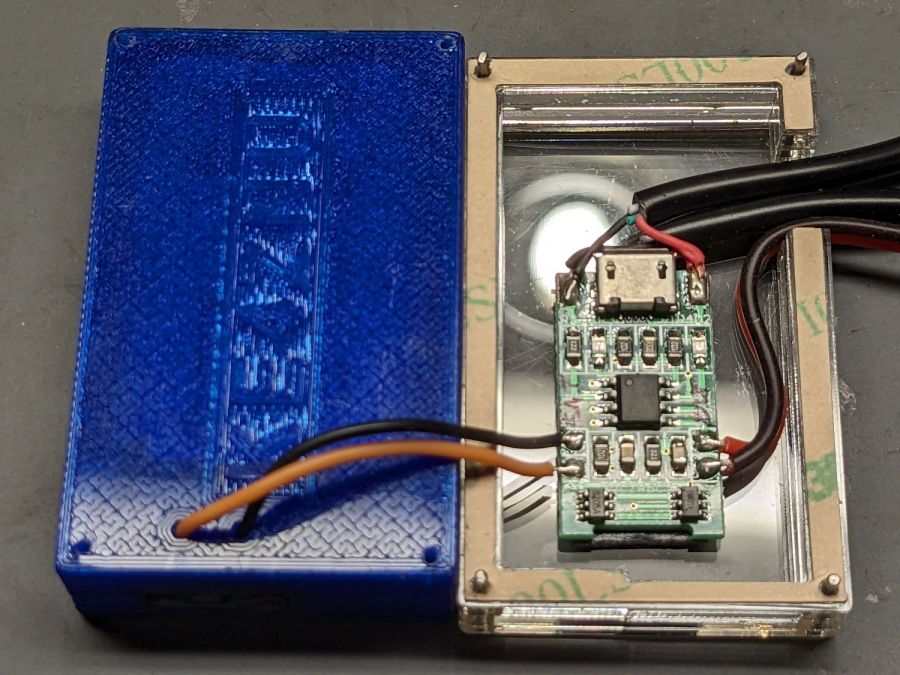

With all that in hand, wire it up:

The USB charger PCB sits atop a layer of double-sided foam tape. After verifying that the circuitry worked, I globbed the wires in place with hot-melt glue to make it less rickety than the picture suggests.

The alert reader will have noticed the holes in the 3D printed NP-BX1 holder were drilled, not printed. In the unlikely event I need another case, the holes will automagically appear in the right place.

I haven’t yet peeled the protective paper off that top adhesive sheet to make a permanent assembly:

We use the car so infrequently that it’ll take a while to build up enough confidence to stick it together and stick it to the dashboard.

On the whole, it’s ugly but sufficient to the task.

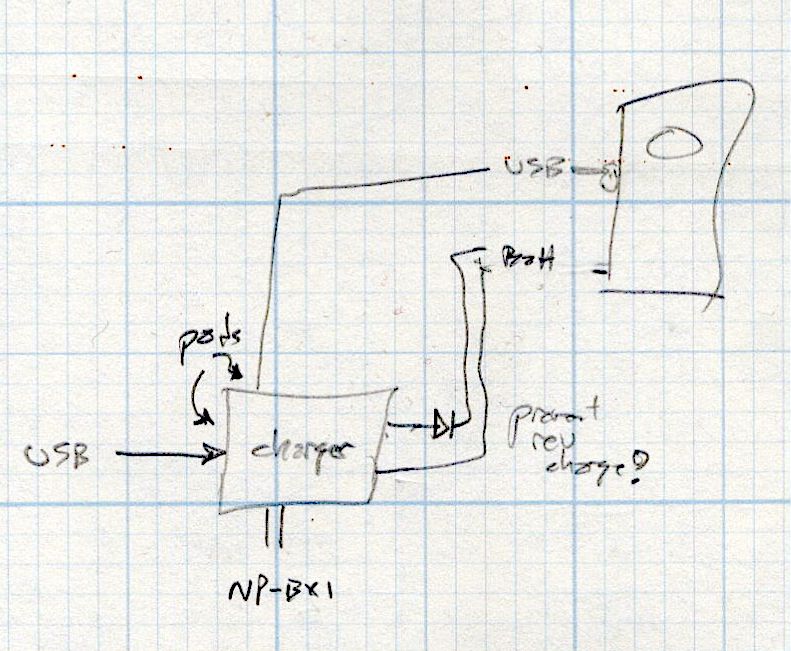

A doodle with key dimensions, plus some ideas not surviving contact with reality:

I truly hope this entire effort is a waste of time.