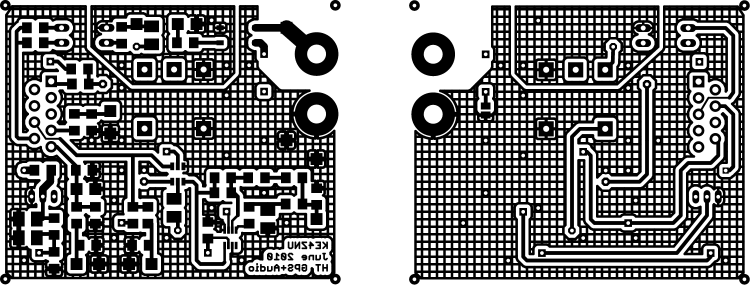

Early on, I decided that the whole APRS + voice interface for our bikes had to fit on the back of the radio, which meant it had to look a lot like a BP-171 battery pack. The first step was to get all the relevant dimensions from an existing pack.

I laid a (rebuilt) pack on the scanner and took its picture. There’s a lip on the bottom (top in the image), so I held it level with the end of the calipers you can see near the bottom. That puts it slightly above the scanner’s focal plane, but it’s close enough.

Then I scanned some graph paper (remember that?) with 10 lines per inch, overlaid that on the pack image, rotated to line it up with the pack, scaled the grid so that the major lines were 1 cm apart on the pack in both directions, and that gave me a nice 1 mm grid to eyeball the measurements.

Printed the image out at about twice real size and there you have it:

The doodles around the bottom give the Z-axis dimensions for tabs & contact slots & suchlike.

The notes near the top were a first pass at how to mill the thing; two years later, the actual G-Code bears little resemblance to that.

I put the origin at the lower-left corner of the part that fits into the radio body, 2.4 mm inside the left edge that mates with the outside of the body. That was probably a mistake, as it meant I had to touch off the final part at X=-2.4 rather than just 0.0.

We live & learn.