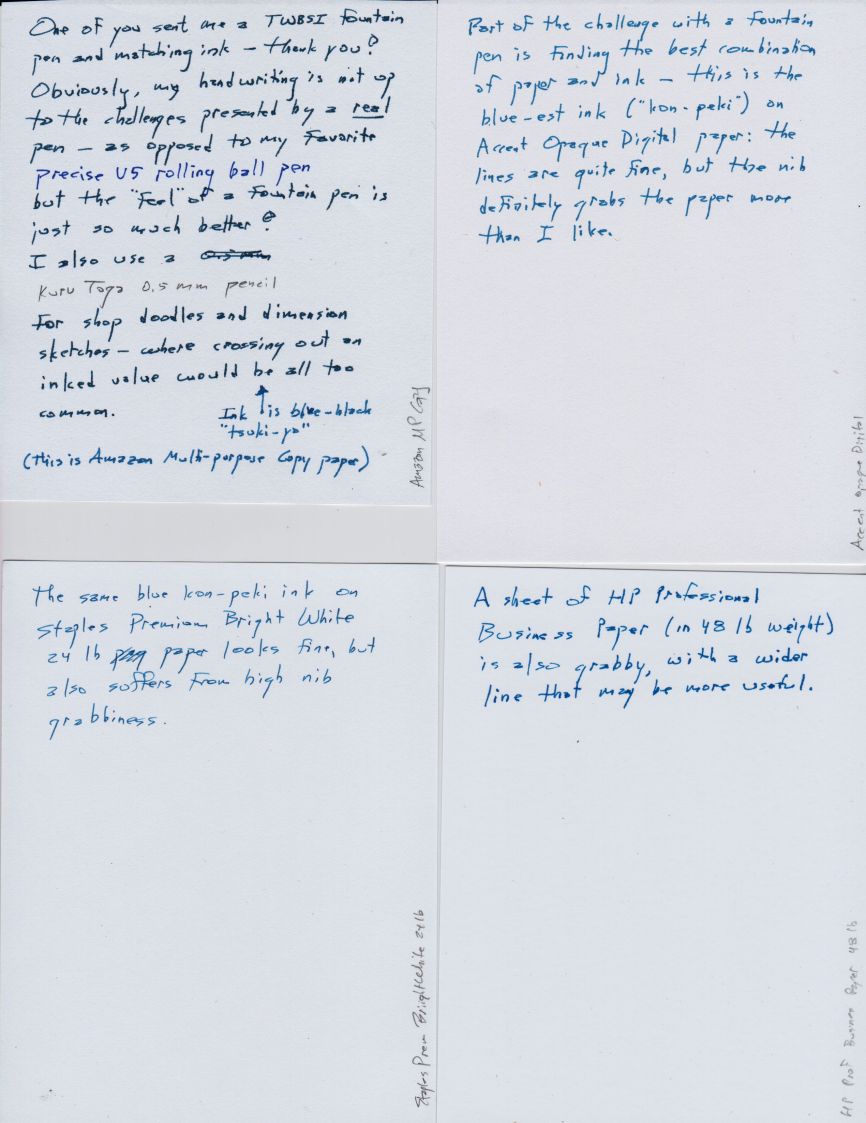

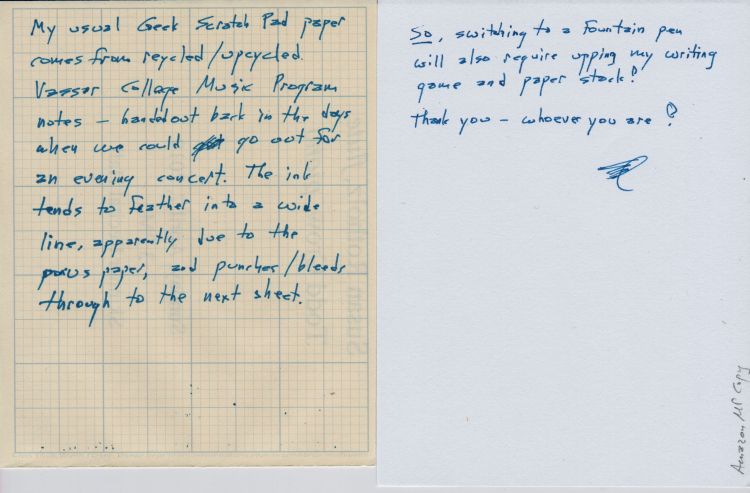

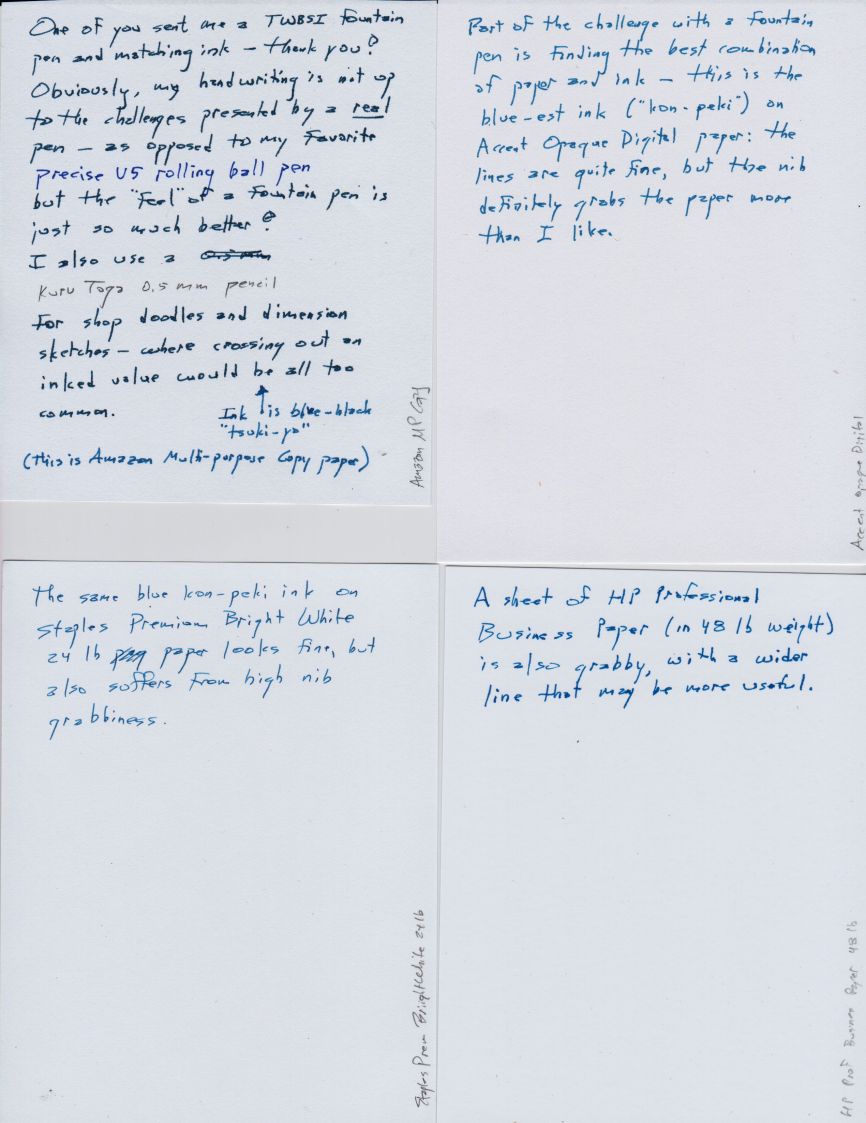

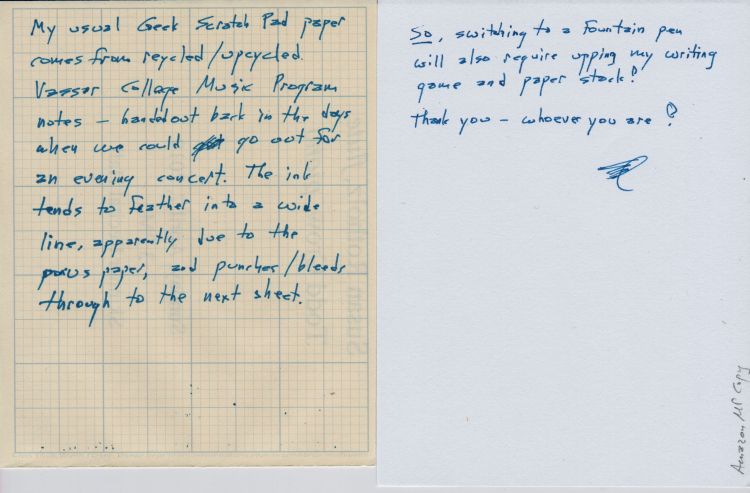

A present arrived:

Man, my handwriting printing is terrible.

The Smell of Molten Projects in the Morning

Ed Nisley's Blog: Shop notes, electronics, firmware, machinery, 3D printing, laser cuttery, and curiosities. Contents: 100% human thinking, 0% AI slop.

Mechanical widgetry

A present arrived:

Man, my handwriting printing is terrible.

A lithium battery management system can (and should!) disable the battery output to prevent damage from overcurrent or undervoltage, after which it must be reset. The inadvertent charge port short may have damaged the BMS PCB, but did not shut down the battery’s motor output, which means the BMS will not should not require resetting. However, because all this will happen remotely, it pays to be prepared.

A description of how to reset the BMS in a similar battery involves poking bare hot wires into the battery terminals, which IMO is akin to Tickling The Dragon’s Tail. The alert reader will note that the “Shark” battery shown on that page has its terminal polarity exactly opposite of the “Ultra Slim Shark” battery on our bikes. Given the energies involved, eliminating any possible errors makes plenty of sense.

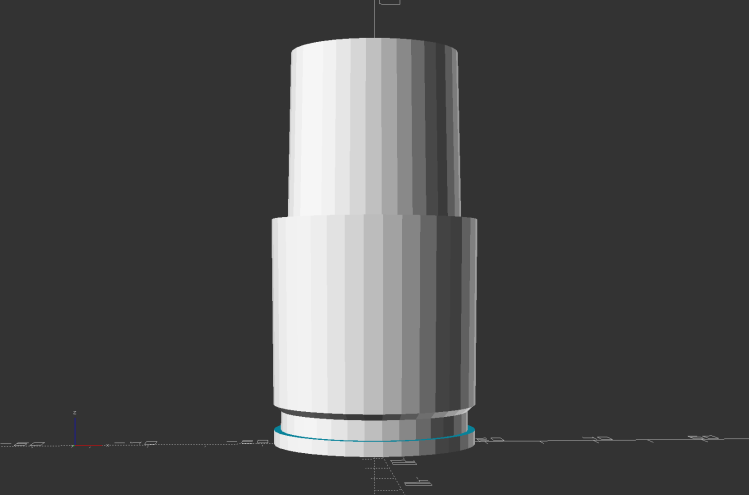

The battery connector looks like this:

For this battery, the positive terminal is on the right, as shown by the molded legend and verified by measurement.

A doodle with various dimensions, most of which are pretty close:

Further doodling produced a BMS reset adapter keyed to fit the battery connector in only one way:

Which turned into the rectangular lump at the top of the tool kit, along with the various shell drills and suchlike discussed earlier:

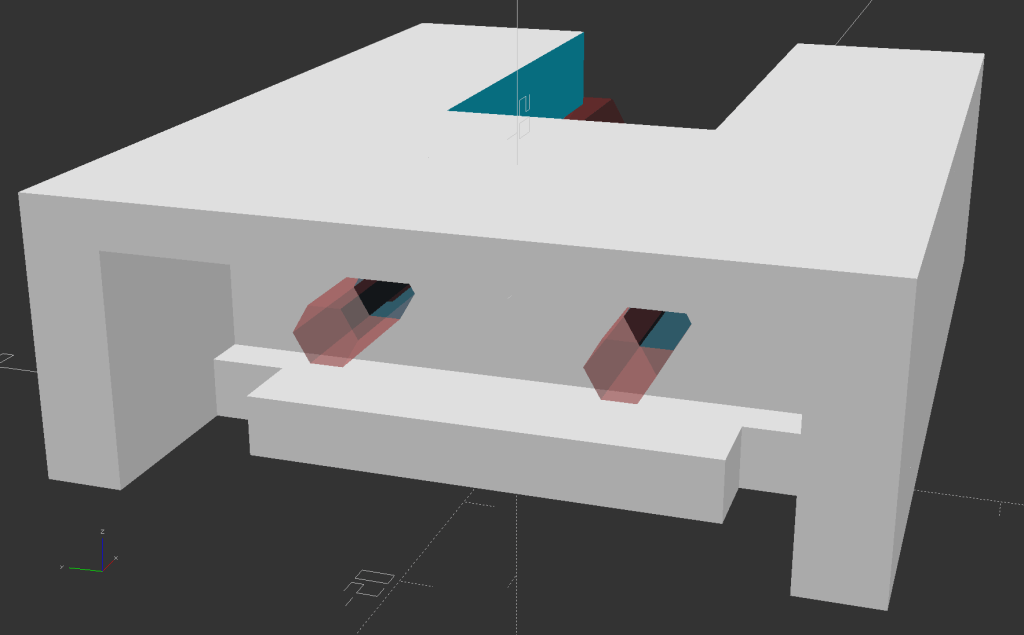

Looking into the solid model from the battery connector shows the notches and projections that prevent it from making incorrect contact:

The pin dimensions on the right, along with a mysterious doodle that must have meant something at the time :

The pins emerged from 3/16 inch brass rod, with pockets for the soldered wires:

The wires go into a coaxial breakout connector that’s hot-melt glued into the recess. The coaxial connectors are rated for 12 V and intended for CCTV cameras, LED strings, and suchlike, but I think they’re good for momentary use at 48 V with minimal current.

I printed the block with the battery connector end on top for the best dimensional accuracy and the other end of the pin holes held in place by a single layer of filament bridging the rectangular opening:

I made a hollow punch to cut the bridge filaments:

The holes extend along the rectangular cutout for the coaxial connector, so pressing the punch against the notch lines it up neatly with the hole:

Whereupon a sharp rap with a hammer clears the hole:

A dollop of urethane adhesive followed the pins into their holes to lock them in place. I plugged the block and pins into the battery to align the pins as the adhesive cured, with the wire ends carefully taped apart.

After curing: unplug the adapter, screw wires into coaxial connector, slobber hot melt glue into the recess, squish into place, align, dribble more glue into all the gaps and over the screw terminals, then declare victory.

It may never be needed, but that’s fine with me.

[Update: A few more doodles with better dimensions and fewer malfeatures appeared from the back of the bench.]

The OpenSCAD source code as a GitHub Gist:

| // Adapter to reset Bafang battery management system | |

| // Ed Nisley KE4ZNU Dec 2021 | |

| Layout = "Block"; // [Show, Build, Pins, Block, CoaxAdapter, Key] | |

| Gap = 4.0; | |

| /* [Hidden] */ | |

| ThreadThick = 0.25; | |

| ThreadWidth = 0.40; | |

| HoleWindage = 0.2; | |

| Protrusion = 0.1; // make holes end cleanly | |

| inch = 25.4; | |

| function IntegerMultiple(Size,Unit) = Unit * ceil(Size / Unit); | |

| module PolyCyl(Dia,Height,ForceSides=0) { // based on nophead's polyholes | |

| Sides = (ForceSides != 0) ? ForceSides : (ceil(Dia) + 2); | |

| FixDia = Dia / cos(180/Sides); | |

| cylinder(d=(FixDia + HoleWindage),h=Height,$fn=Sides); | |

| } | |

| ID = 0; | |

| OD = 1; | |

| LENGTH = 2; | |

| //———————- | |

| // Dimensions | |

| WallThick = 3.0; | |

| PinSize = [3.5,4.75,9.0 + WallThick]; // LENGTH = exposed + wall | |

| PinFerrule = [3.5,4.75,10.0]; // larger section for soldering | |

| PinOC = 18.0; | |

| PinOffset = [-9.0,0,9.0]; | |

| Keybase = 4.0; // key bottom plate thickness | |

| KeyBlockSize = [15.0,50.0,15.0]; | |

| CoaxSize = [35.0,15.0,11.0]; | |

| CoaxGlue = [0,2*2,1]; | |

| // without key X section | |

| BlockSize = [CoaxSize.x + WallThick + PinFerrule[LENGTH],KeyBlockSize.y,KeyBlockSize.z + WallThick]; | |

| echo(BlockSize=BlockSize); | |

| //———————- | |

| // Battery connection pin | |

| // Used to carve out space for real brass pin | |

| // Long enough to slide ferrule through block | |

| module Pins() { | |

| for (j=[-1,1]) | |

| translate(PinOffset + [0,j*PinOC/2,0]) | |

| rotate([0,90,0]) | |

| rotate(180/6) { | |

| PolyCyl(PinSize[ID],BlockSize.x,6); | |

| translate([0,0,PinSize[LENGTH]]) | |

| PolyCyl(PinSize[OD],BlockSize.x,6); | |

| } | |

| } | |

| //———————- | |

| // Coaxial socket adapter nest | |

| // X=0 at left end of block, Z=0 at bottom | |

| // includes glue, extends rightward to ensure clearance | |

| module CoaxAdapter() { | |

| translate([0,0,CoaxSize.z]) | |

| cube(CoaxSize + CoaxGlue + [CoaxSize.x,0,CoaxSize.z],center=true); | |

| } | |

| //———————- | |

| // Block without key | |

| // X=0 at connector face, Z=0 at bottom of block | |

| module BareBlock() { | |

| difference() { | |

| translate([BlockSize.x/2,0,BlockSize.z/2]) | |

| cube(BlockSize,center=true); | |

| Pins(); | |

| translate([BlockSize.x,0,Keybase]) | |

| CoaxAdapter(); | |

| } | |

| translate([BlockSize.x – CoaxSize.x,0,BlockSize.z/2]) // bridging layer | |

| cube([ThreadThick,BlockSize.y,BlockSize.z],center=true); | |

| } | |

| //———————- | |

| // Complete block | |

| module Block() { | |

| BareBlock(); | |

| BatteryKey(); | |

| } | |

| //———————- | |

| // Battery connector key shape | |

| // Chock full of magic sizes | |

| // Polygons start at upper left corner | |

| module BatteryKey() { | |

| // base outline | |

| kb = [[-15,KeyBlockSize.y/2],[0,KeyBlockSize.y/2],[0,-KeyBlockSize.y/2],[-15,-KeyBlockSize.y/2]]; | |

| // flange cutout | |

| kf = [[kb[0].x,20],[-3,20],[-3,15],[-8,15],[-8,-15],[-3,-15],[-3,-20],[kb[0].x,-20]]; | |

| // sidewalls | |

| kw = [[-15,KeyBlockSize.y/2],[0,KeyBlockSize.y/2],[0,20],kf[0]]; | |

| linear_extrude(height=Keybase) | |

| difference() { | |

| polygon(kb); | |

| polygon(kf); | |

| } | |

| linear_extrude(height=KeyBlockSize.z) | |

| polygon(kw); | |

| mirror([0,1,0]) | |

| linear_extrude(height=KeyBlockSize.z) | |

| polygon(kw); | |

| translate([0,0,KeyBlockSize.z]) | |

| linear_extrude(height=BlockSize.z – KeyBlockSize.z) | |

| polygon(kb); | |

| } | |

| //———————- | |

| // Build it | |

| if (Layout == "Block") { | |

| BareBlock(); | |

| } | |

| if (Layout == "Pins") { | |

| Pins(); | |

| } | |

| if (Layout == "Key") { | |

| BatteryKey(); | |

| } | |

| if (Layout == "CoaxAdapter") { | |

| CoaxAdapter(); | |

| } | |

| if (Layout == "Show") { | |

| Block(); | |

| color("Brown",0.3) | |

| Pins(); | |

| } | |

| if (Layout == "Build") { | |

| rotate([0,90,0]) | |

| translate([-BlockSize.x,0,0]) | |

| Block(); | |

| } | |

Continuing to mull the problem of removing a brass nugget fused to the center pin of the Bafang battery’s charge port without the risk of causing further damage suggested a shell drill fitting over the pin and guided by an insulating bushing:

That’s our undamaged battery, now sporting labels inspired by my friend’s mishap.

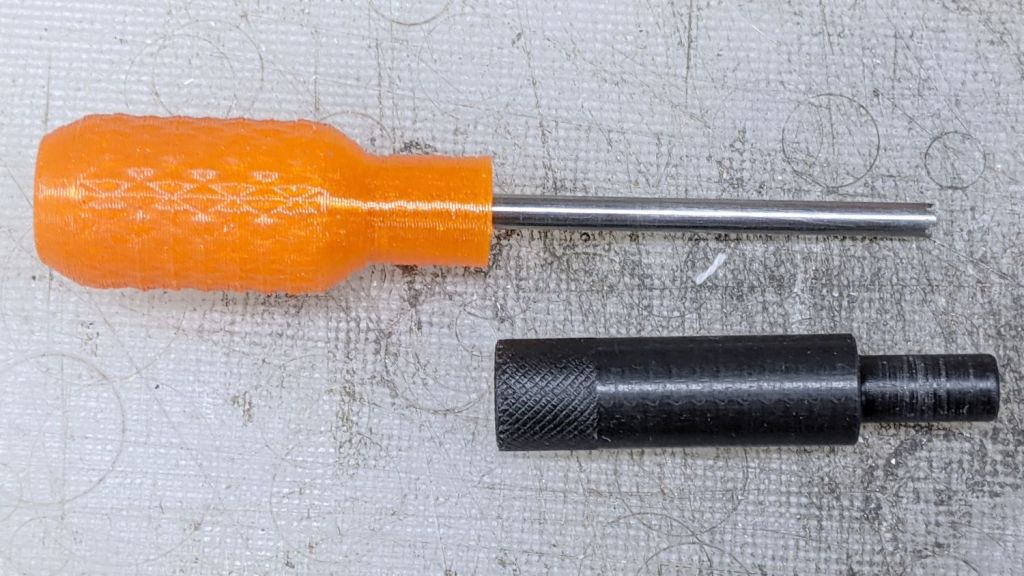

The first pass was a 3 mm (actually, 1/8 inch) brass tube rammed into a printed handle descending from the Sherline Tommy Bar handles:

The black stuff is coarse grinding compound held on by a dot of oil, with a pair of notches filed into the tip for a little griptivity.

This worked surprisingly well, at least if you weren’t in much of a hurry, although the grinding compound also erodes the drill:

I hadn’t thought this through enough to realize there’s no good way to convince the grit to not work its way up into the acetal bushing and jam the rod. While this might be good for final polishing, it’s not going to work well against the nugget, so it’s time for a harder drill with real teeth.

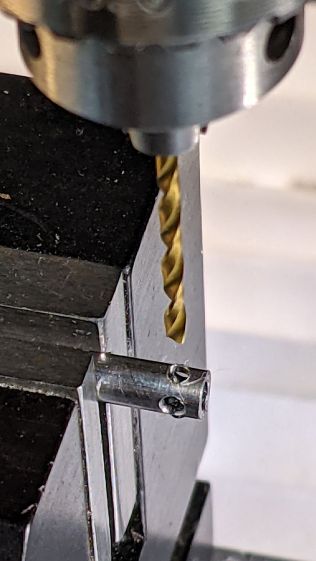

Drilling a 2.3 mm hole into the end of some non-hardened 3 mm (for real!) ground rod provided enough clearance for the charge port pin and a pair of cross-drilled holes laid the groundwork for a shell drill:

I filed the end off down to leave about 3/4 of the holes, then applied a Swiss pattern file with a safe edge to cut some relief behind the tips:

It would be better to harden the end of the rod, but this is a single-use tool.

Ram the shank into another printed handle:

The new drill is long enough to reach past the wounded end of the pin and short enough to not bottom out inside the connector.

A few minutes of twirling and re-filing the tiny teeth improved the cut enough to produce a convincing result in the simulated connector:

I’m reasonably sure the ID of the acetal bushing won’t fit over the nugget, but that’s easy enough to drill out while leaving an insulating shell.

The charge port’s center pin probably can’t withstand too much torque, so the drill must take small cuts.

Vacuuming out the chips while cutting will be critical, as you don’t want an accumulation of conductive chaff down in the hole!

Rather than poke things into the undamaged charge port of our battery, I built a quick-and-dirty mechanical duplicate:

The “center pin” is a snippet of what’s almost certainly 5/64 inch brass tube measuring Close Enough™ to 2.1 mm, with a few millimeters of 3/32 inch tube soldered on the end to simulate the nugget.

The aluminum rod has a 5.5 mm hole matching the coaxial jack’s diameter and depth, with a smaller through hole for the “pin” and a dab of Loctite bushing adhesive.

Then I turned the end of a 3/8 inch acetal rod down to a 5.5 mm bushing that completely fills the jack:

It has a 3 mm hole down the middle to aim homebrew shell drills directly at the pin, while preventing a short to the side contact.

The first test looked encouraging:

The nugget in the damaged jack is definitely larger than my soldered brass tube, but this was in the nature of exploratory tinkering while mulling the problem.

Short-circuiting the Bafang battery’s charge port may have done anything from completely destroying the battery management circuit to just welding a brass nugget onto the port’s center pin. The main output to the bike motor remained functional, so my friend used it on rides over the next few days to reduce the charge level.

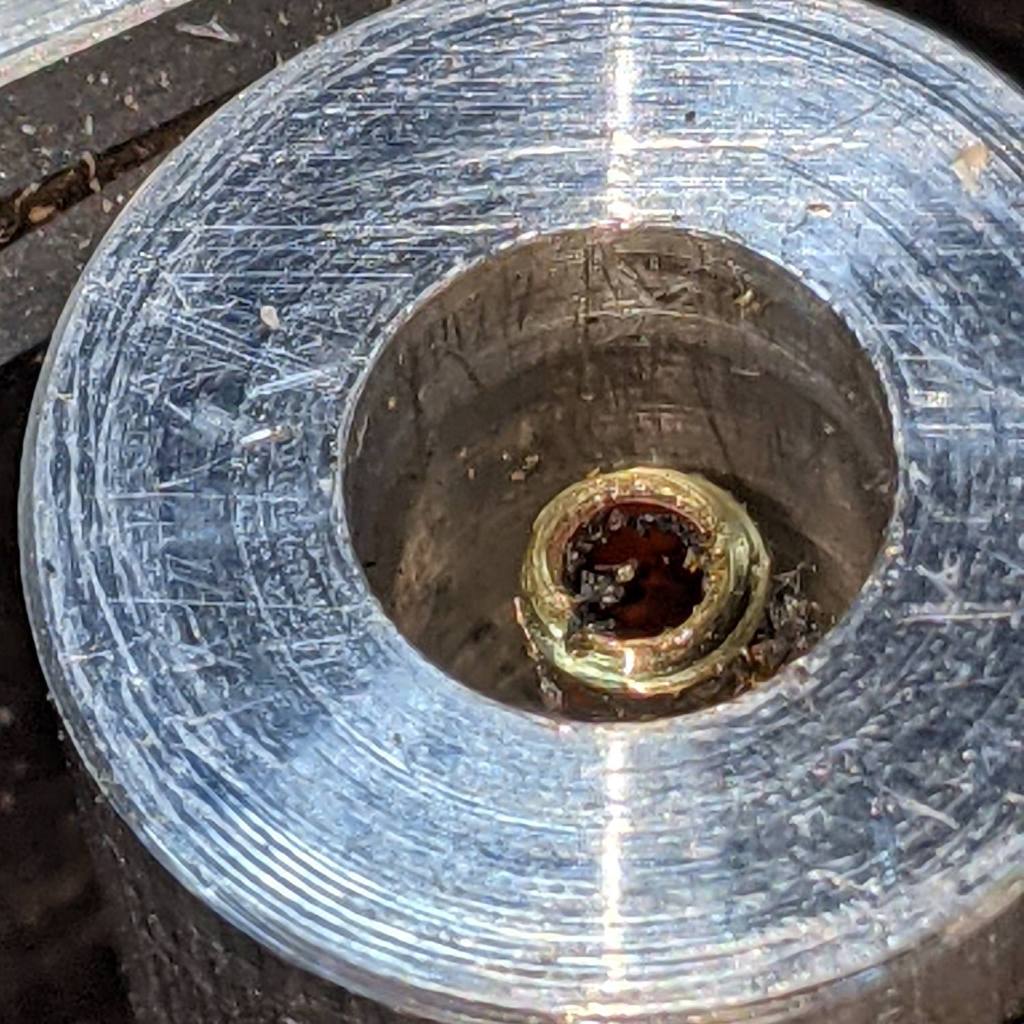

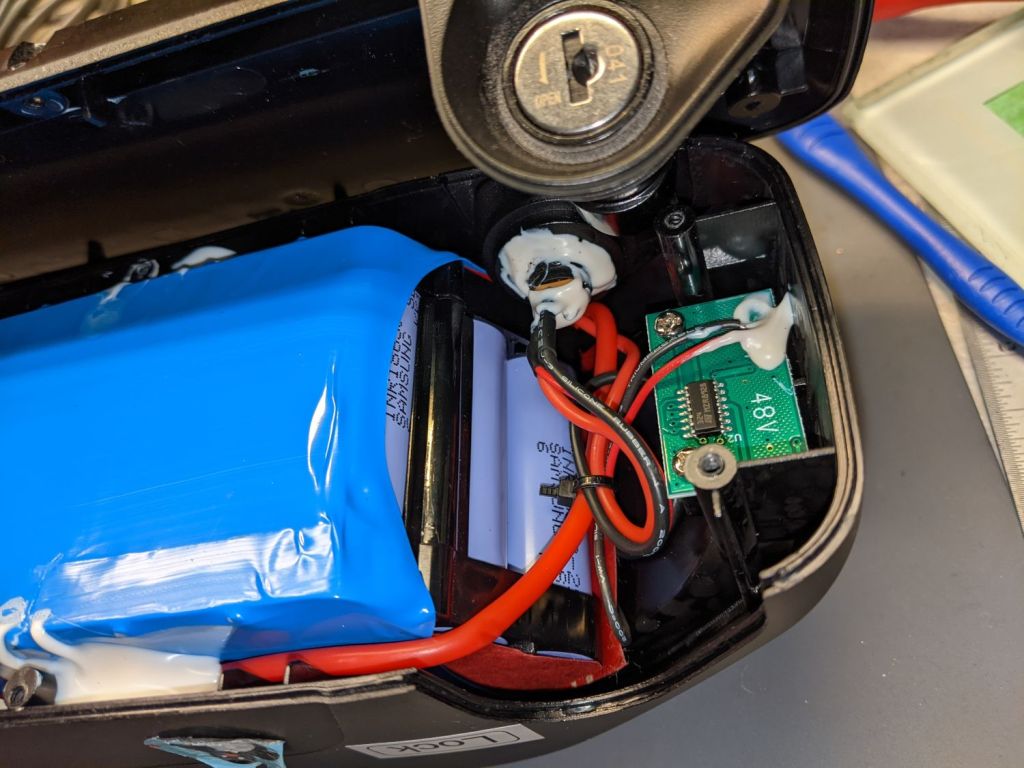

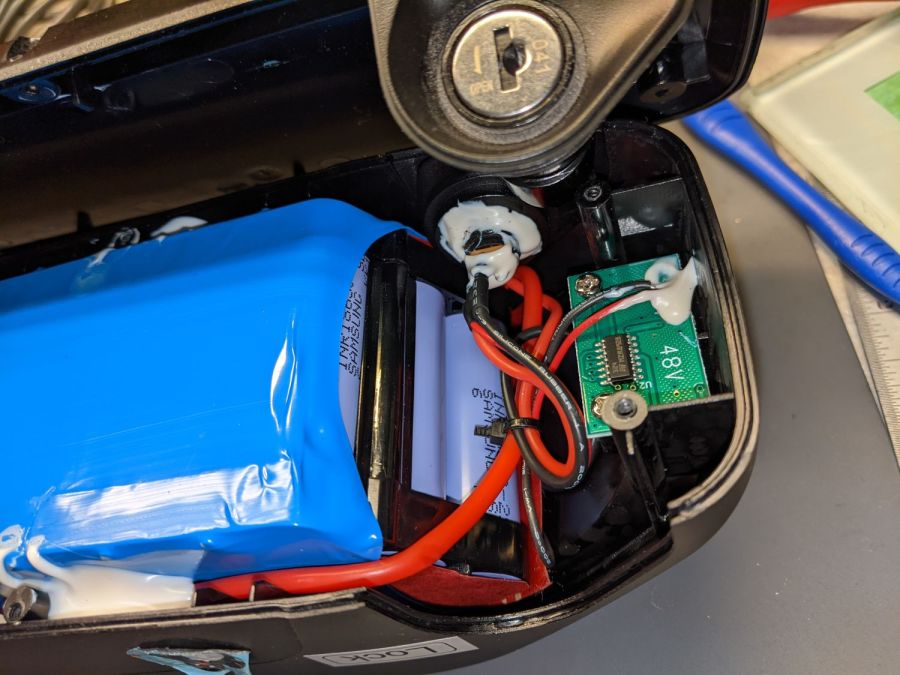

Meanwhile, I peeked inside the undamaged battery on Mary’s bike:

The battery pack is neatly shrink-wrapped and firmly glued into the plastic shell, with the battery management PCB on the other side of the battery. Some gentle prying suggests it will be difficult to disengage the adhesive, so getting the pack out will likely require cutting the blue wrap, extricating the cells as an unbound set, then cutting the blue wrap to release the wires.

A closer look at the nose of the battery:

The large red wire entering on the left comes from the motor connector, loops around the nose of the battery, and probably connects to the battery’s most positive terminal or, perhaps, to the corresponding BMS terminal.

The medium black wire from the side contact of the coaxial jack (atop the pair of red wires) burrows under the battery and likely connects to the most negative battery terminal. This is the charger plug’s outer terminal.

The small red wire from the center contact of the coaxial jack (between the medium black and red wires) goes to the charge indicator PCB in the nose of the battery. This is basically a push-to-test voltmeter with four LEDs indicating the charge state from about 40 V through 54 V. The small black wire from that PCB burrows under the battery on its way to the BMS.

The medium red wire from the center contact goes to the BMS.

There is no way to determine how much damage the short might have done, although the silicone-insulated wires should have survived momentary heating, unlike cheap PVC insulation that slags down at the slightest provocation.

Removing and replacing the coaxial jack requires Cutting Three Wires then rejoining them, a process fraught with peril. You must already have a profound respect for high voltages, high currents, and high power wiring; this is no place for on-the-job learning and definitely not where you can move fast and break things.

With this in mind, the only hope is to remove the nugget and see if the battery charges properly.

The trick will be to do this without any possibility of shorting a metallic tool between the center pin and the side contact.

The Bafang mid-drive e-bike kits I installed on Mary’s Tour Easy recumbent and a friend’s Terry Symmetry used the “Ultra-Slim Shark” lithium battery, a rectangular lump with a tapered snout:

The battery has a key lock on its left side:

The lock might deter casual thievery, but really prevents the battery from bouncing out of its mounting plate while riding.

The right side has a charge port closed with a rubber plug:

The cover protects a coaxial jack with a 5.5 mm OD and a 2.1 mm center pin:

My friend in Raleigh generally removes the battery before hoisting the bike into the back of her car to haul it to a friend’s house for their companionable rides: not lifting an additional seven pounds is a Good Idea™.

A momentary distraction in the middle of that process caused her to insert the brass key into the charging port, rather than the lock. The key put a very short circuit between the coaxial jack’s side contact and the center pin, melting the key tip and welding a brass nugget onto the side of the pin:

The charger plug normally sits almost flush to the port’s surface:

The nugget keeps the plug out the damaged port, preventing the plug from making electrical contact:

She owned the problem and immediately bought another battery, which tells you the value she places on riding her e-bike.

Verily it is written: let someone who is without whoopsie cast the first shade.

Any takers? Yeah, the way I see it, someone who says they’ve never done anything quite like that is either not doing anything or not telling the complete truth. For sure, I’ve done plenty of inadvertent damage!

Here’s the problem:

How would you proceed?

More to come …

For reference:

Basically, it is possible to ship lithium batteries up to 100 W·h.

My tool adapters for the Dirt Devil stick vacuum cleaner worked fine when inserted into the power unit, but got stuck in the floor brush extension tube:

The adapter rotated freely inside the socket, so its diameter was correct and it wasn’t jammed, but pushing the latch button (at the depression on the right) didn’t release the adapter.

Popping the latch out of the tube let the adapter slide easily out of the socket and exposed the innards:

The two bosses inside the latch originally captured a nice conical spring:

The tab on the left side of the latch button engages a slot in the OEM brush head and the recessed ring around my adapters:

It turns out the molded tab was slightly too long, so pushing the latch button all the way down didn’t retract the tab out of the bore, so it remained engaged in the adapter’s ring.

The conical spring also didn’t seem to collapse completely flat, so the bosses inside the latch button couldn’t quite bottom out, leaving the tab protruding even further inside the bore. It also required an inordinate amount of force to push the latch all the way down.

While fiddling with all this, I noticed that the OEM floor brush would sometimes hang up on the tab, so the operation wasn’t all that smooth even with the original equipment.

So I trimmed maybe half a millimeter off the tab, just enough to release the adapter with the button fully pressed and without the conical spring, then replaced the conical spring with a tiny spring (from the Big Box o’ Random Springs) trimmed to allow the full range of travel. This not only released the adapter, it also let the OEM floor brush pop out more easily.

A zero-dollar repair, although with considerable annoyance.