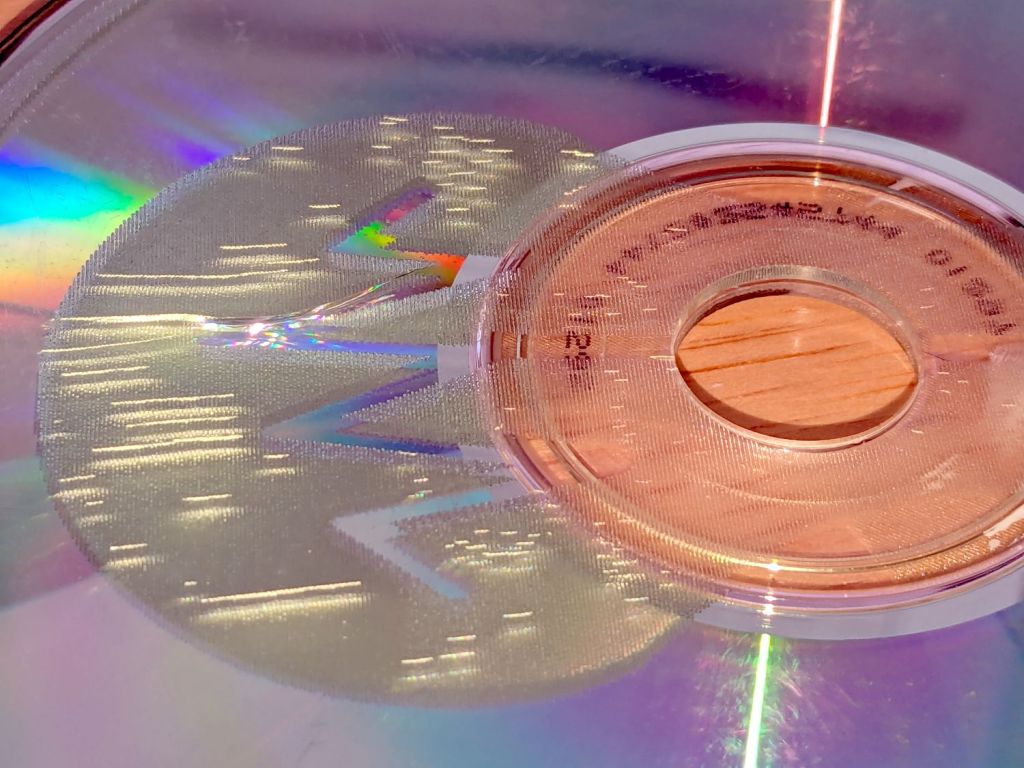

I asked for the images from recent X-ray and MRI sessions, whereupon a CD arrived in the mail. Popping it into my desktop Linux box produced this directory listing:

ll /run/media/ed/Feb\ 21\ 2025/

total 146M

dr-xr-xr-x 2 ed ed 136 Feb 21 13:14 ./

drwxr-x---+ 3 root root 60 Mar 2 13:40 ../

-r--r--r-- 1 ed ed 146M Feb 21 13:14 -NISLEY-DMBG8yMQcf8qXcVj.iso

It seems whoever / whatever produced the CD copied the ISO image to the CD, rather than burning the ISO directly to the CD. As a result, the CD has one file.

Raise your hand if you’ve never done that.

Well, I was going to save the CD as an ISO file anyway, so I just copied it to the file server.

Attempting to mount it produces an odd result:

sudo mount -o loop "-NISLEY-DMBG8yMQcf8qXcVj.iso" /mnt/loop/

[sudo] password for ed: <make up your own>

mount: failed to set target namespace to ISLEY-DMBG8yMQcf8qXcVj.iso: No such file or directory

Oh, right, starting a filename with a leading dash is never a Good Idea™.

Rename it:

mv -NISLEY-DMBG8yMQcf8qXcVj.iso NISLEY-DMBG8yMQcf8qXcVj.iso

mv: invalid option -- 'N'

Try 'mv --help' for more information.

Which is why leading dashes are a Terrible Idea™.

Force the rename to happen:

mv ./-NISLEY-DMBG8yMQcf8qXcVj.iso NISLEY-DMBG8yMQcf8qXcVj.iso

The same syntax works in the mount command, but it’s easier to solve the problem once and be done with it.

Now mount the file:

sudo mount NISLEY-DMBG8yMQcf8qXcVj.iso /mnt/loop

mount: /mnt/loop: WARNING: source write-protected, mounted read-only.

That’s entirely expected, because the whole filesystem is intended for a non-writeable CD.

What’s inside?

ll /mnt/loop/

ls: cannot open directory '/mnt/loop/': Permission denied

Why would that be?

ll /mnt

total 58K

drwxr-xr-x 15 root root 4.0K May 21 2023 ./

drwxr-xr-x 17 root root 4.0K Mar 2 13:43 ../

… omitted …

drwxrwx--- 4 496 495 2.0K Feb 21 13:13 loop/

… omitted …

Maybe 496 and 495 are the UID and GID of whatever created the CD?

Force it to my UID:

sudo umount /mnt/loop

[ed@shiitake tmp]$ sudo mount -o uid=ed NISLEY-DMBG8yMQcf8qXcVj.iso /mnt/loop

mount: /mnt/loop: WARNING: source write-protected, mounted read-only.

[ed@shiitake tmp]$ ll /mnt/loop

total 16K

drwxrwx--- 4 ed 495 2.0K Feb 21 13:13 ./

drwxr-xr-x 15 root root 4.0K May 21 2023 ../

drwxrwx--- 4 ed 495 2.0K Feb 21 13:12 data/

drwxr-xr-x 5 ed 495 2.0K Feb 21 13:13 DICOM/

-rw-rw---- 1 ed 495 1.7K Feb 21 13:12 README.txt

-rw-rw---- 1 ed 495 3.2K Feb 21 13:12 view-studies.html

Now that’s more like it.

Finally, I can fire up Weasis to look at pretty DICOM images:

Apparently things looks suspicious around L4.