I have a pair of underseat packs on my Tour Easy that have sagged rather badly over the years. That might have something to do with the fact that my toolkit and other odds & ends weighs more than some bike frames; while I don’t need that stuff very often, it’s good to have around.

Tools & suchlike live in the left-side pack, the near one in the photo, and you can see the problem. The right-side pack holds HT batteries, my belt pack, and other relatively lightweight stuff; I’ll fix that one when I see whether this works. The panniers at the rear wheel are for groceries and other bulky items. The trailer, well, that’s how we do groceries…

Anyway, the underseat packs have a black plastic (styrene?) backing that cracked under the stress of the stuff inside, allowing the top corners to cave in and the bottom to droop.

The hooks holding the pack to the underseat rack were riveted through the backing sheet and the hardware, but a couple of good shots with a punch broke them free.

Some rummaging in the Parts Heap turned up a big acrylic sheet (“100 times stronger than glass!”) that’s absolutely the wrong material for the job: it’s too brittle. However, I’d like to see whether a stiff backplate will solve the problem or if I’m going to have to get ambitious and build an internal pack frame.

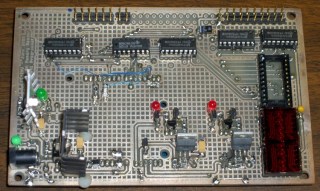

It’s essentially impossible to get a picture of a project built largely from acrylic sheet, but here goes.

I traced the outline of the old backplate onto the new sheet’s protective paper, introduced it to Mr Belt Sander to get those nice round corners, then drilled the holes. It turns out to not be quite symmetric, so there’s a right way and a wrong way to insert it into the pack.

All the hardware is stainless steel. They used aluminum rivets, which is the only reason I could punch them out without too much difficulty, that I’m replacing with SS 10-32 machine screws & nuts.

The aluminum stiffener is a random chunk of ribbed extrusion from the Heap; the original was almost exactly twice as long as one backplate, so the two halves (one for the other pack) are precisely right. I milled out the center rib around the nuts to get enough clearance for a nut driver.

Herewith, a closeup of the hardware. There’s an acrylic sheet in there, honest, it’s under the aluminum extrusion and fender washer. Really!

I put an automobile license plate in the bottom of each underseat pack to act as a floor for all the crap inside; it’s an almost perfect fit and should give you an idea of the pack’s size. It also maintains the bottom’s rectangular shape and keeps heavy stuff from sagging; there’s a hole scuffed in the bottom from the intersection of a high curb and just such an oversight.

Having washed the pack while it was apart (there’s a first time for everything), it looks a lot better than it did before. The yellow block in the front pocket is the kickstand plate mentioned there. It used to have a mesh pocket along the side, too, but that snagged on something and got pretty well ripped, so Mary trimmed it off when she sewed a patch over the aforementioned hole.

It’s still saggy, but the top corners of the plate are holding it up a lot better now. If they crack again, I might just have to go with some aluminum sheet.

These packs seem to be obsolete. The ERRC Lloonngg panniers (search for them) seem to be, well, too long for most purposes; they look as though they would interfere with ordinary rack packs. If I were doing it over, I’d look into hacking a pair of smallish duffel bags.