Having previously concluded running the CNC 3018-Pro steppers from 12 V would let the DRV8825 chips provide better current control in Fast Decay mode at reasonable speeds, I wondered what effect a 24 V supply would have at absurdly high speeds with the driver in 1:8 microstep mode to reduce the IRQ rate.

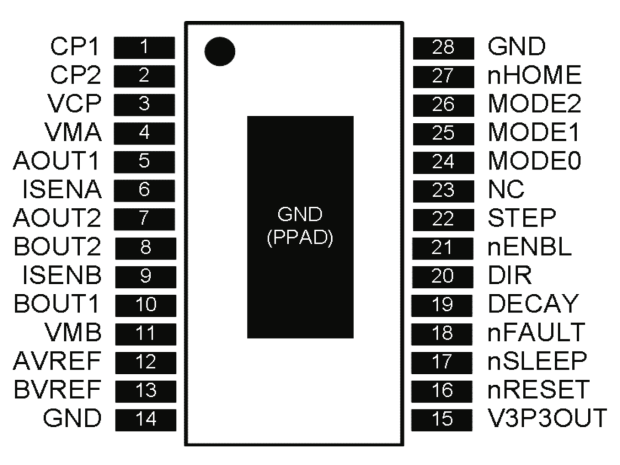

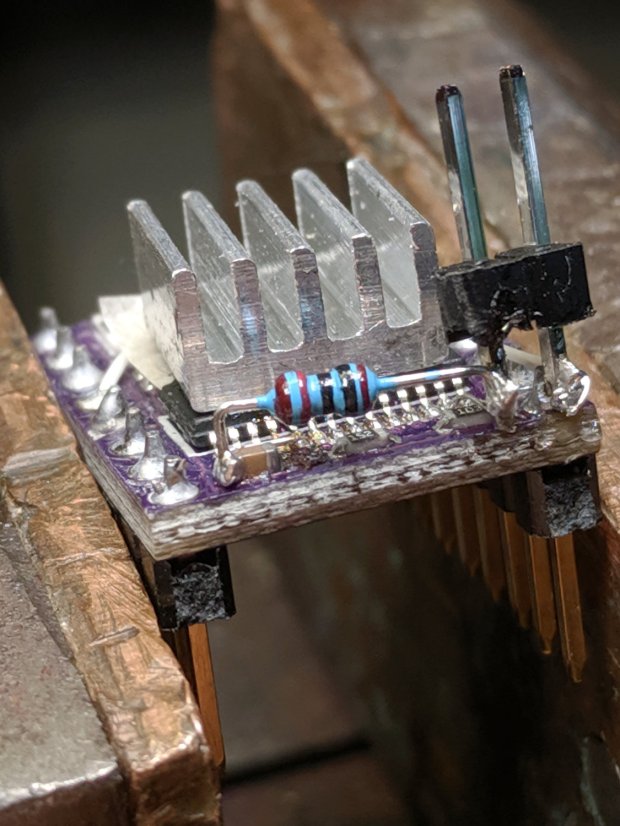

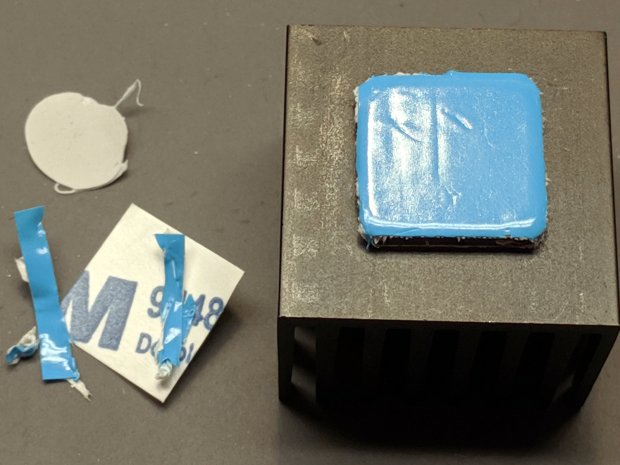

So, in what follows, the DRV8825 chip runs in 1:8 microstep mode with Fast Decay current control. You must apply some hardware hackage to the CAMTool V 3.3 board on the CNC 3018-Pro to use those modes.

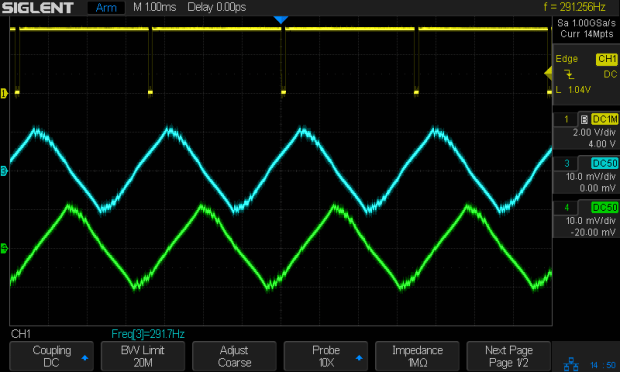

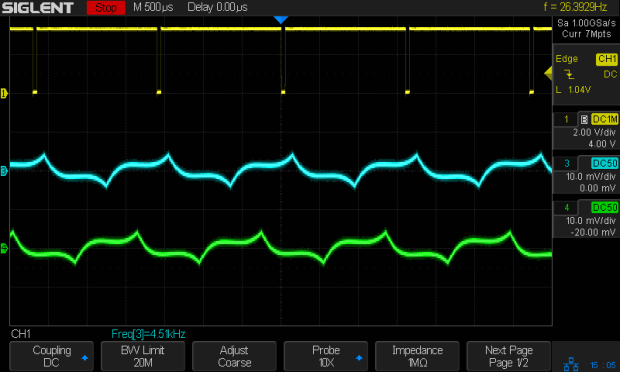

In all the scope pix, horizontal sync comes from the DRV8825 Home pulse in the top trace, with the current in the two windings of the X axis motor in the lower traces at 1 A/div. Because only the X axis is moving, the actual axis speed matches the programmed feed rate.

Homework: figure out the equivalent two-axis-moving speed.

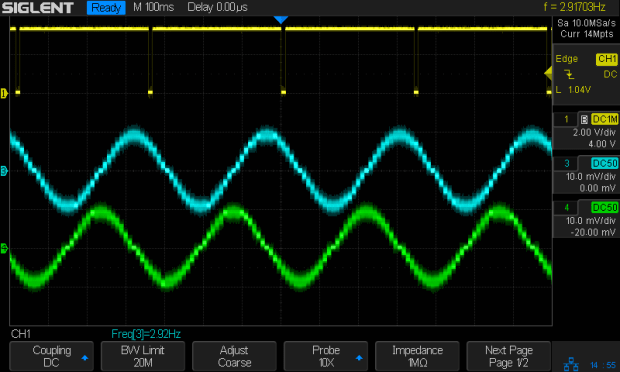

The 12 V motor supply works well at 140 mm/min, with Fast Decay mode producing clean microstep current levels and transitions:

The sine waves deteriorate into triangles around 1400 mm/min, suggesting this is about as fast as you’d want to go with a 12 V supply:

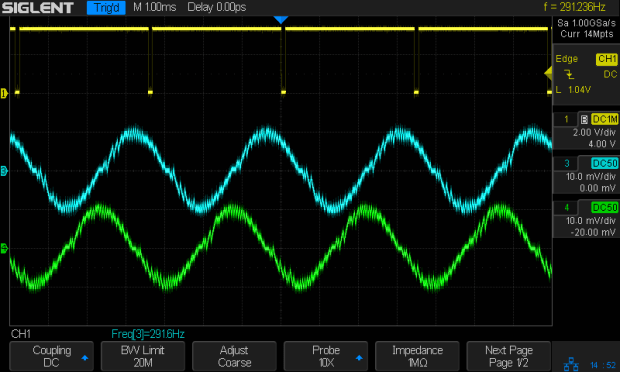

Although the axis can reach 3000 mm/min, it’s obviously running well beyond its limits:

The back EMF fights the 12 V supply to a standstill during most of the waveform, leaving only brief 500 mA peaks, so there’s no torque worth mentioning and terrible position control.

Increasing the supply to 24 V, still with 1:8 microstepping and Fast Decay …

At a nose-pickin’ slow 14 mm/min, Fast Decay mode looks rough, albeit with no missteps:

At 140 mm/min, things look about the same:

For completeness, a detailed look at the PWM current control waveforms at 140 mm/min:

The dead-flat microstep in the middle trace happens when the current should be zero, which is comforting.

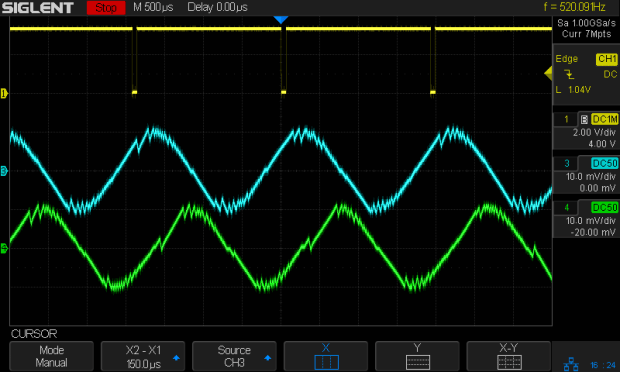

At 1400 mm/min, where the 12 V waveforms look triangular, the 24 V supply has enough mojo to control the current, with increasing roughness and slight undershoots after the zero crossings:

At 2000 mm/min, the DRV8825 is obviously starting to have trouble regulating the current against the increasing back EMF:

At 2500 mm/min, the back EMF is taking control away from the DRV8825:

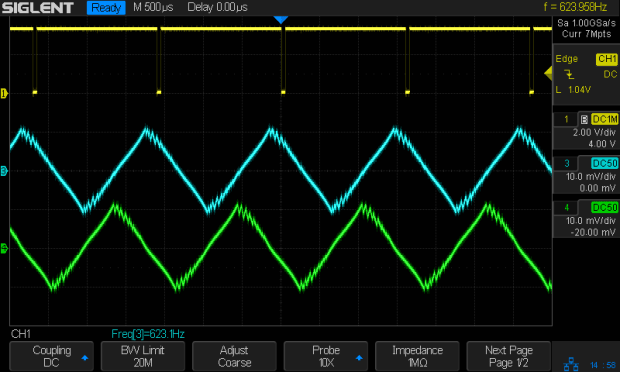

The waveforms take on a distinct triangularity at 2700 mm/min:

They’re fully triangular at 3000 mm/min:

In round numbers, you’d expect twice the voltage to give you twice the speed for a given amount of triangularity, because the current rate-of-change varies directly with the net voltage. I love it when stuff works out!

At that pace, the X axis carrier traverses the 300 mm gantry in 6 s, which is downright peppy compared to the default settings.

Bottom lines: the CNC 3018-Pro arrives with a 24 V supply that’s too high for the DRV8825 drivers in Mixed Decay mode and the CAMTool V3.3 board’s hardwired 1:32 microstep mode limits the maximum axis speed. Correcting those gives you 3000 mm/min rapids with good-looking current waveforms.

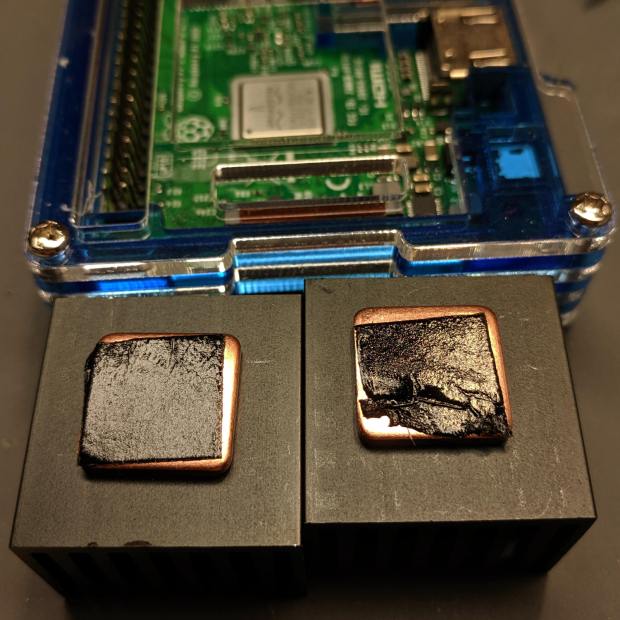

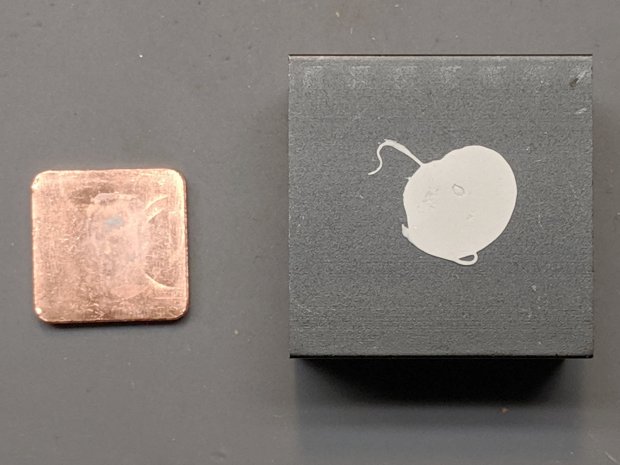

I’m reasonably sure engraving plastic and metal disks at 3000 mm/min is a Bad Idea™, but having some headroom seems desirable.