Putting that battery into the Dell 8100 laptop produced the dreaded blinky light of doom, so it has been on the shelf for maybe half a year. Having gutted the cells from the case, the next step was to discharge the cells completely, thereby producing the lower four curves in this plot:

I arbitrarily labeled the cell pairs 1 through 4. Pair 1 has the lowest remaining charge and the other three seem very closely matched.

I recharged the four cell pairs one-at-a-time from a bench power supply set to 4.2 V. Each pair started charging at about 2 A, somewhat lower than the pack’s 3.5 A limit, so the supply’s 3 A current limit didn’t come into play. You probably don’t want to do this at home, but …

The usual charge regime for lithium cells terminates when the charging current at 4.2 V drops below 3% of the rated current (other sources say 10%, take your pick). The pack’s dataplate sayeth the charging current = 3.5 A, so the termination current = 100 mA. I picked 3% of the initial 2 A current = 60 mA and stopped the charge there, so I think the cells were about as charged as they were ever going to get.

As nearly as I can tell, increasing the voltage enough to charge at a current-limited 3.5 A (a bit beyond my bench supply’s upper limit, but let’s pretend), then reducing the voltage to 4.2 V as the current drops would be perfectly OK and in accordance with accepted practice, but I’m not that interested in a faster charge.

Unlike the other three pairs, Pair 1 quickly became warm and I stopped the charge. Warming is not a nominal outcome of charging lithium-based cells, so those were most likely the cells that caused the PCB to pull the plug on the pack. The other pairs remained cool during the entire charge cycle, the way they’re supposed to behave.

However, even with that limited charge, Pack 1 had about the same capacity as the (presumably) fully charged Pack 2, showing that the cells get most of their charge early in the cycle. Pairs 3 and 4 had more capacity, but they’re not in the best of health.

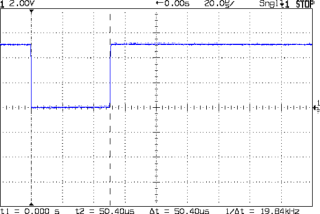

The blue curve in this graph shows the discharge curve for the 1.1 A·h Canon NB-5L battery (actually, a cell) that came with the SX230HS camera:

Notice that it remains above 3.4 V until it produces 1.1 A·h at 500 mA, which is roughly its rated capacity. The other traces come from those crap eBay NB-5L batteries.

The two best pairs of Dell cells can each produce about 1.3 A·h at 1 A before dropping below 3.4 V (the cursor & box mark that voltage in the top graph), so they’re in rather bad shape. Strapping the best two pairs together would give a hulking lump with perhaps three times the life of the minuscule NB-5L battery, so I think that’s probably not worth the effort.

Particularly when one can get a prismatic 3.7 V 5 A·h battery for about $30 delivered, complete with protective PCB and pigtail leads…