Nuheara predicts two to three years of battery lifetime for their IQbuds² MAX not-really-hearing-aids and, indeed, after 2-½ years of more-or-less steady use, the right bud developed a bad case of not charging fully and discharging quickly. The batteries are not, of course, customer-replaceable, so one can:

- Buy a single bud

- Buy a complete new pair + case + accessories

- Ask about their repair service

Unsurprisingly, a single bud costs more than half the cost of the full set and the repair service is a complete mystery. Given that the left bud’s battery will likely fail in short order, let’s find out what’s inside.

Your ear sees this side:

The dark oval is a (probably IR) sensor telling the bud when it’s jammed in your ear.

Everybody else sees this side:

The small slit over on the right and the two holes around the top seem to be for various microphones.

Jamming a plastic razor blade into the junction between the two parts of the case, just under the mic slit, and gently prying around the perimeter eventually forces the adhesive apart:

Do not attempt to yank the two pieces apart, because a ribbon cable joins the lower and upper PCBs:

The metallic disk in the lower part is the lithium battery.

Ease the upper part away, being very careful about not tugging on the ribbon cable:

The battery has moved upward, revealing the lower PCB.

Rolling the upper part toward the ribbon cable eventually produces enough space to extract the battery:

Note the orientation:

- The rebated end is the negative terminal and faces outward

- The wider end is the positive terminal and faces inward

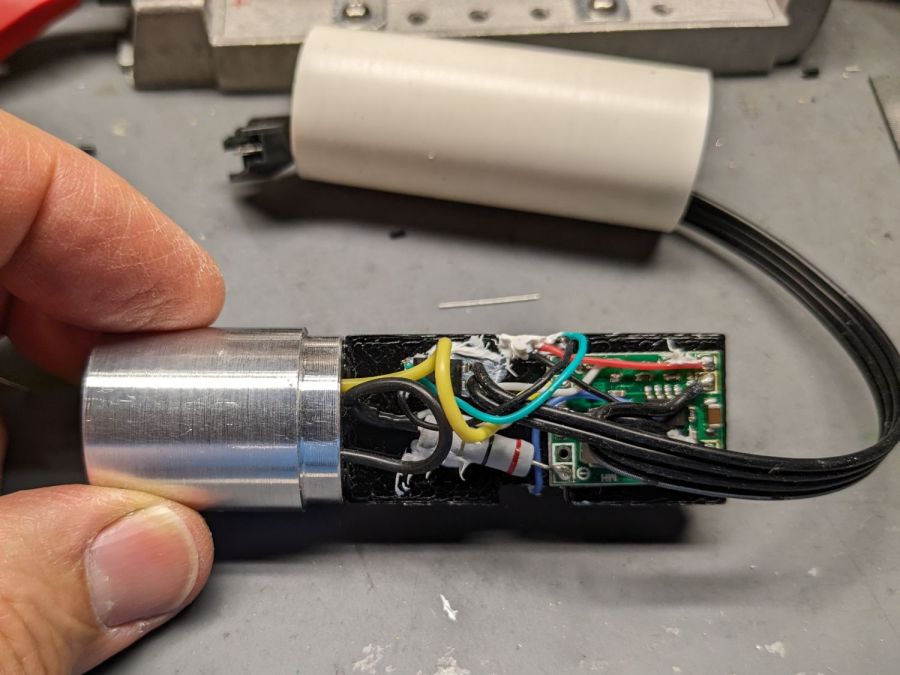

With the battery out, you can admire the PCBs and ribbon cable:

What is not obvious from the picture: two pairs of spring-loaded pogo pins contacting the battery. There is no actual battery holder, as it’s just tucked into the structure of the bud, with the perimeter adhesive providing the restraining force for the pogo pins.

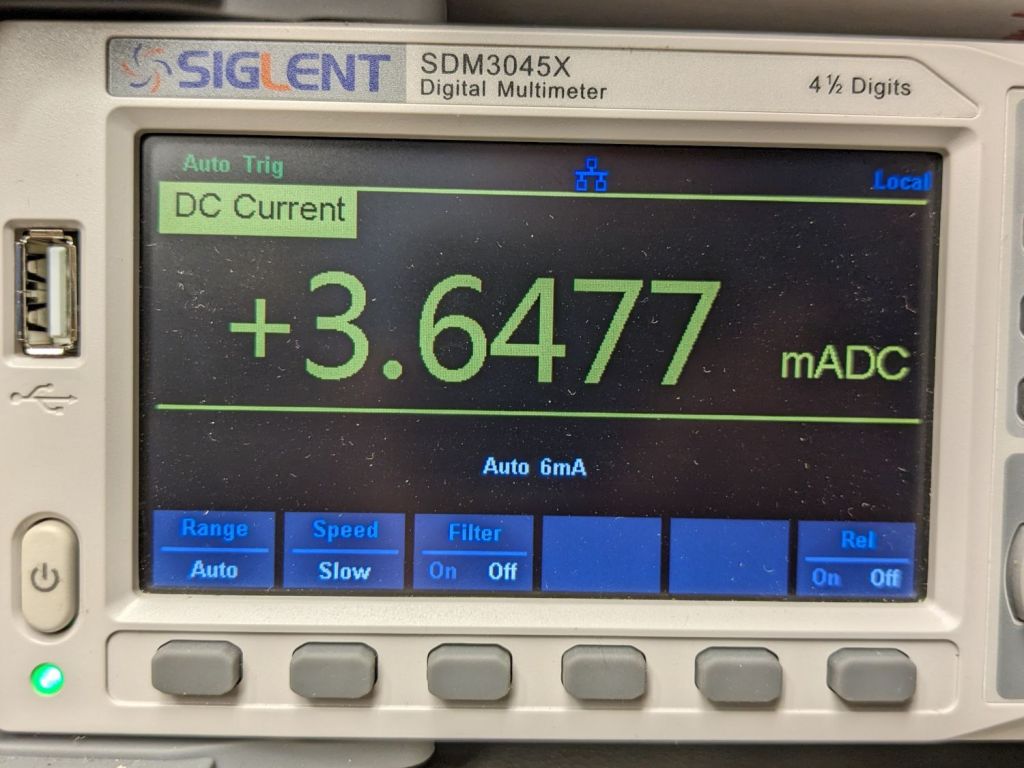

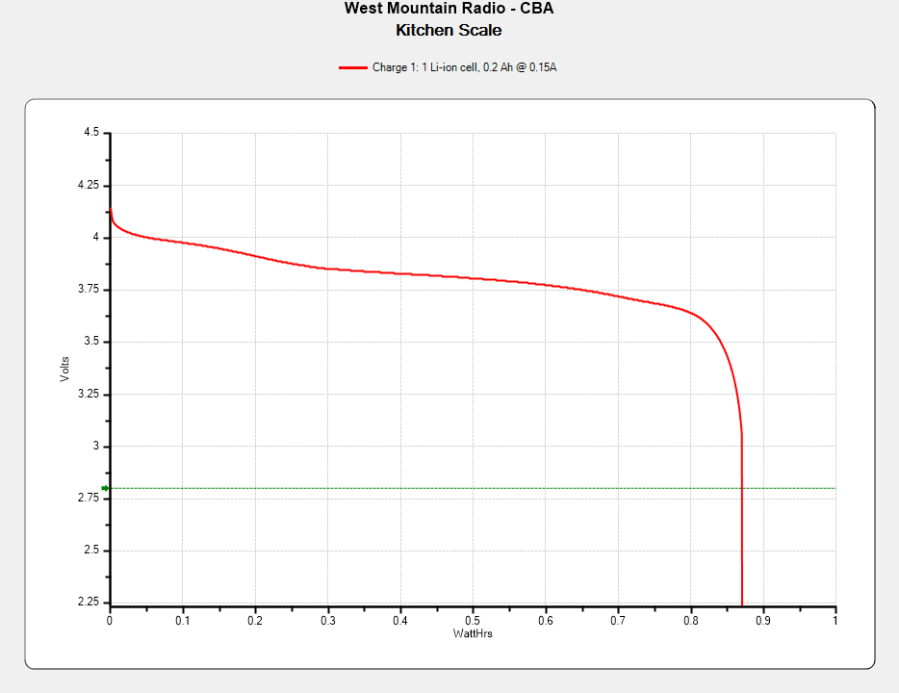

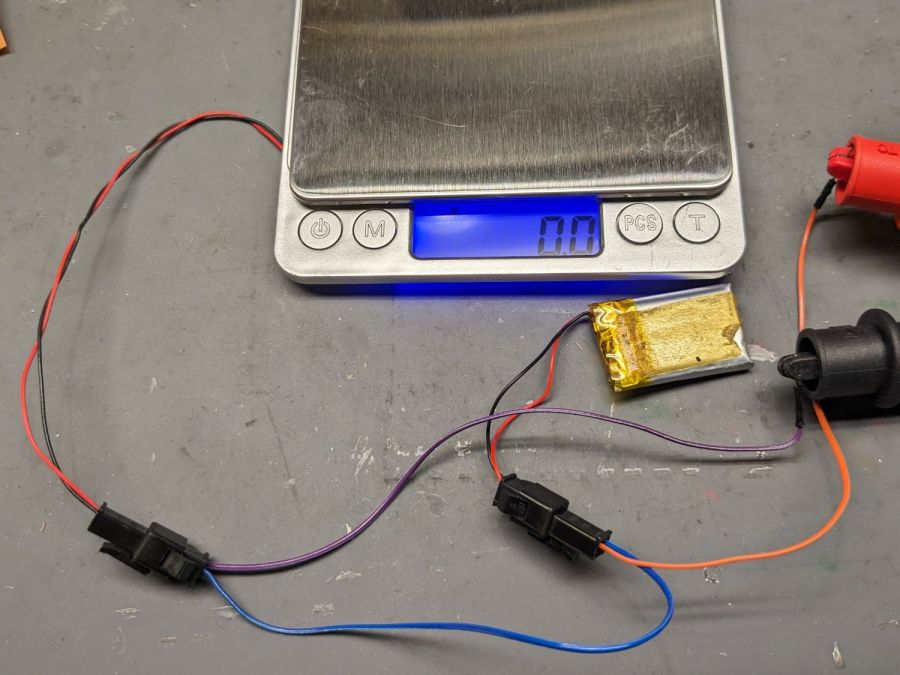

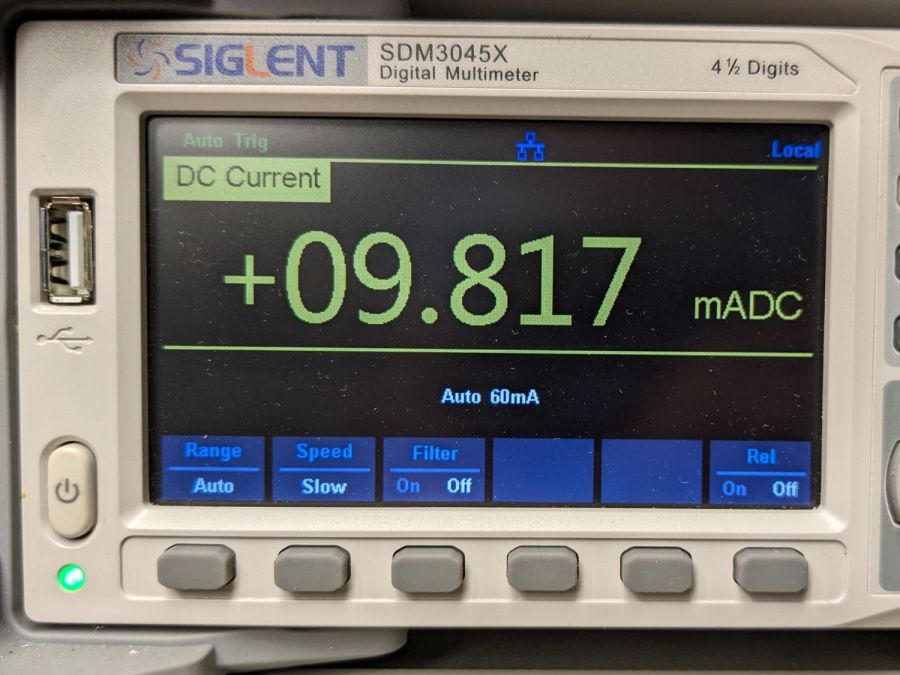

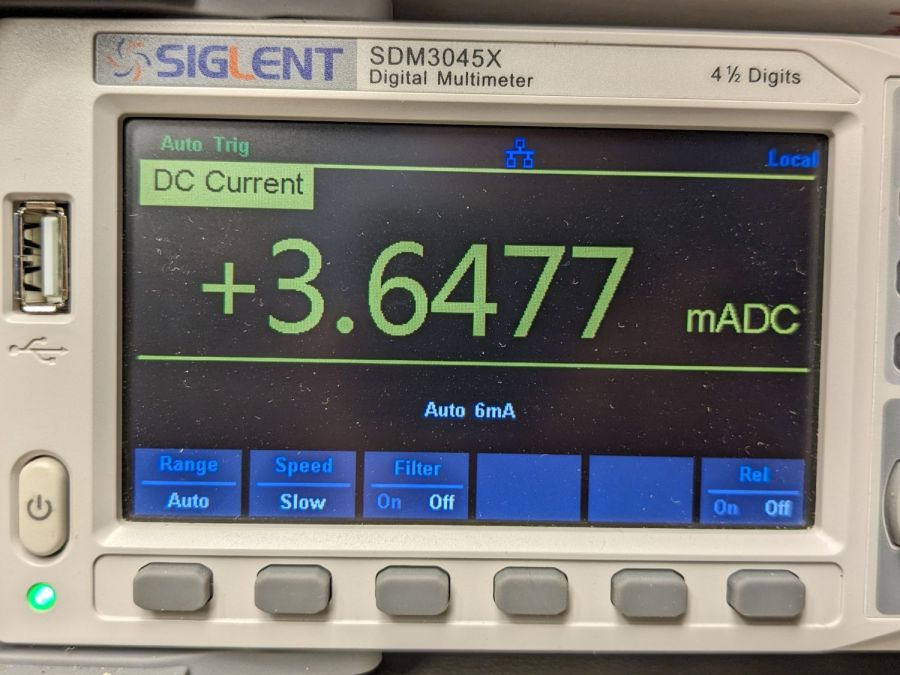

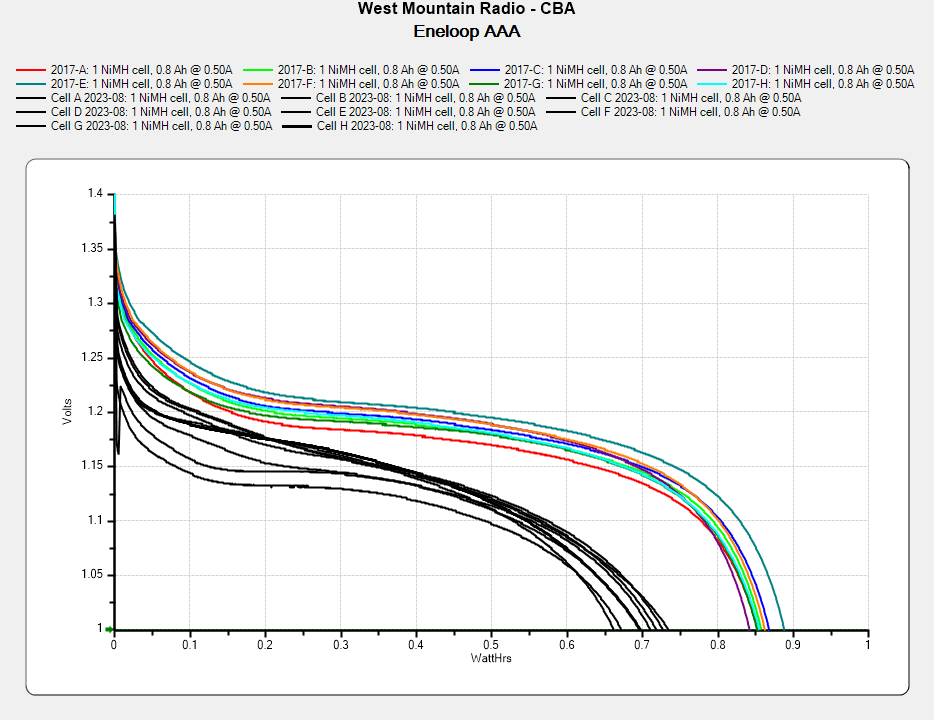

The battery seems a variant of a standard 1654-size lithium cell:

The 1654 cells I got came with wire leads welded to the cell and a complete Kapton enclosure; apparently other devices use soldered connections rather than pins. They proudly proclaim their “Varta” heritage, but I have no way to prove they actually came from Germany.

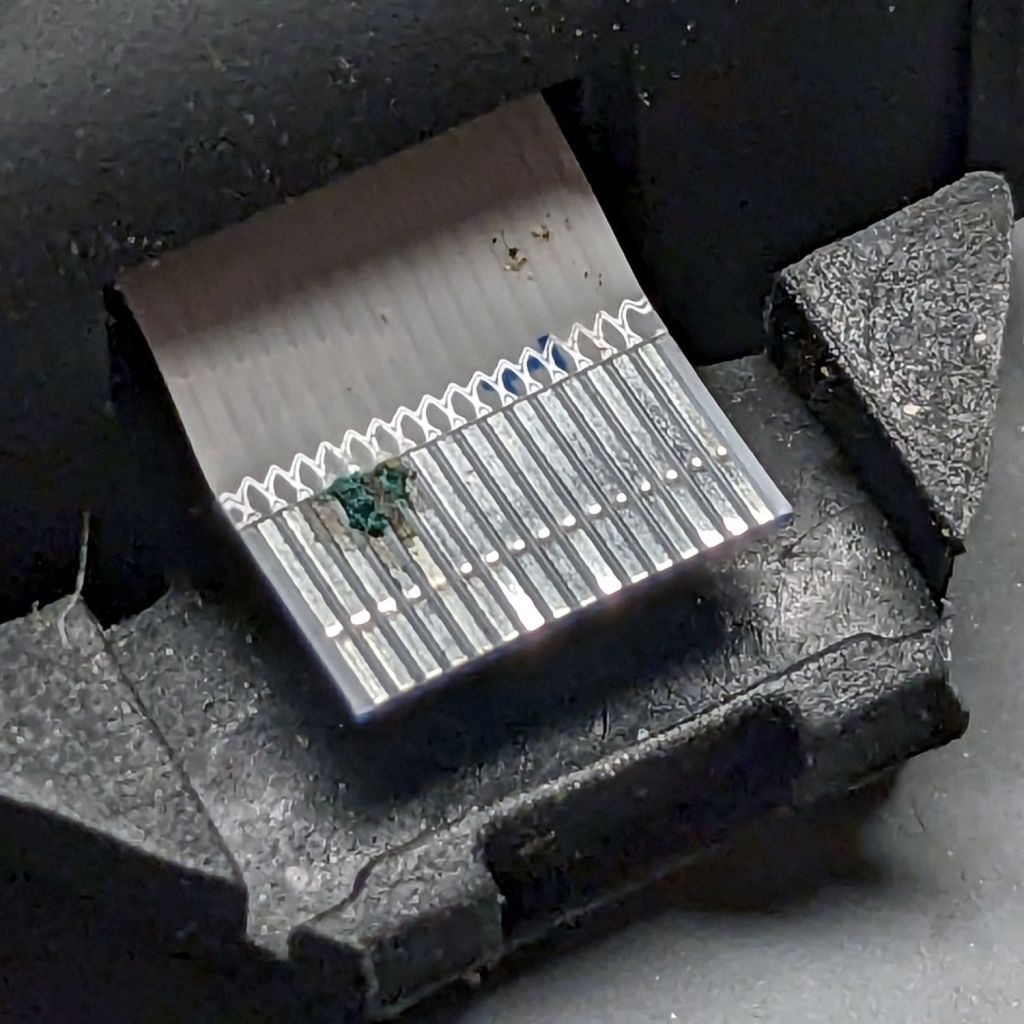

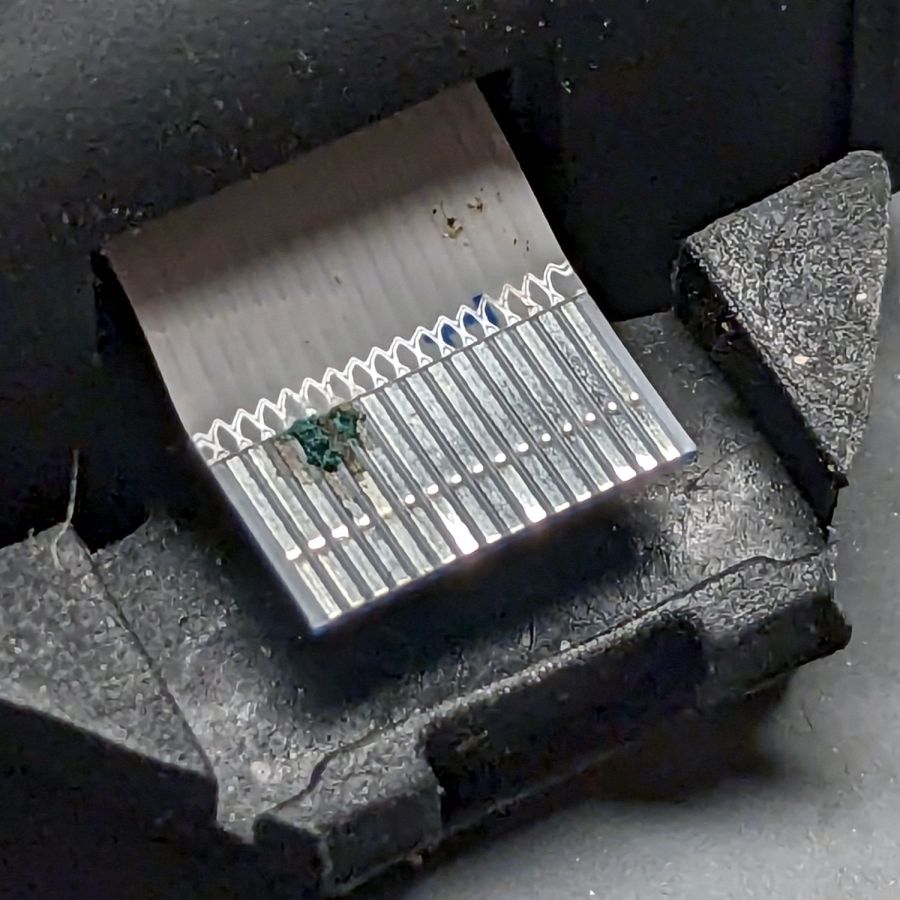

I snipped off the wires, carved a pair of holes through their Kapton for the contact pins, tucked the cell in the bud, pressed the halves together, applied a clamp, then wrapped a strip of Kapton tape around the perimeter:

It seems remarkably easy to wrap the tape over the front microphone, but don’t do that. Conversely, sealing the entire perimeter is the only way to prevent acoustic feedback, so I added a snippet of tape just under the front mic opening.

Do that for the other bud and declare victory.

That is, fer shure, not the most stylin’ repair you’ve ever seen, but I was (for what should be obvious reasons) reluctant to glue the halves together. I expect the tape to peel off / lose traction after a while, but I have plenty of tape at the ready. Worst case, I can glop some adhesive in there and hope for the best.

Because the buds lost power during their adventure, they required a trip through their charging case to wake them up again. After that, they work as well as they did before, with consistently longer run time from both buds.

Whew!