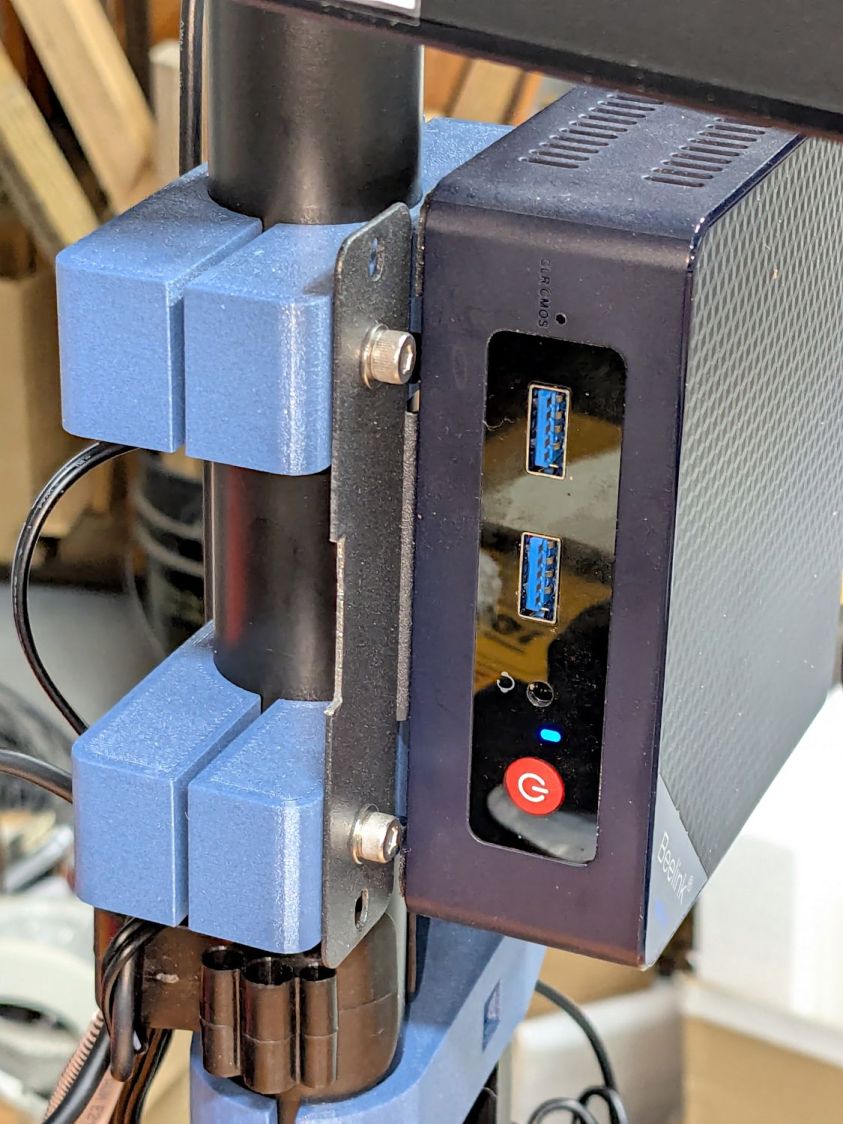

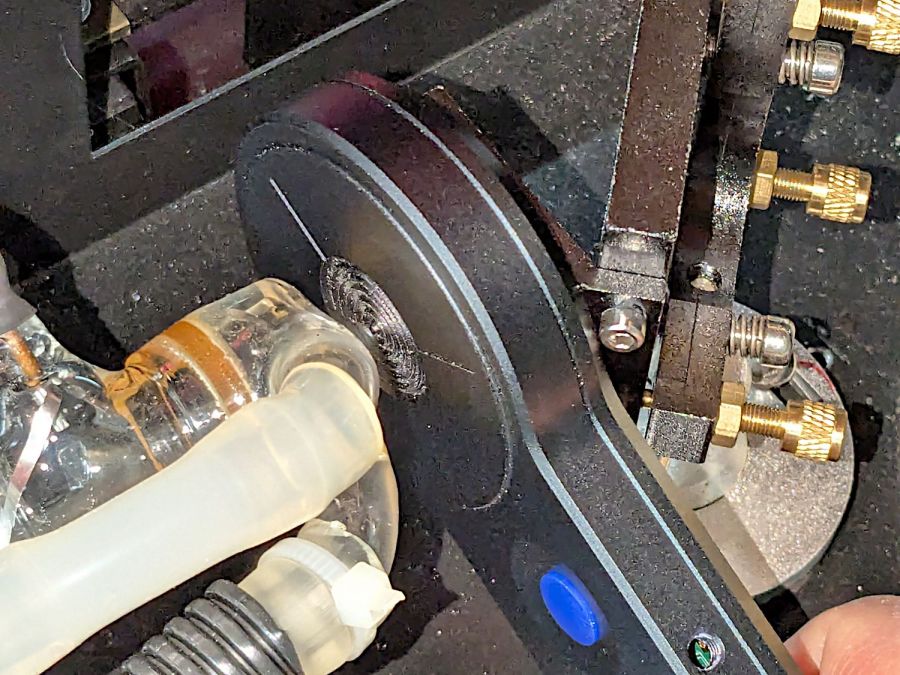

Along with the Beelink PC, putting the Anker USB hub on the monitor mount pole helped tidy the cables just a little bit:

It’s still jumbled, but at least the cables aren’t wagging the hub.

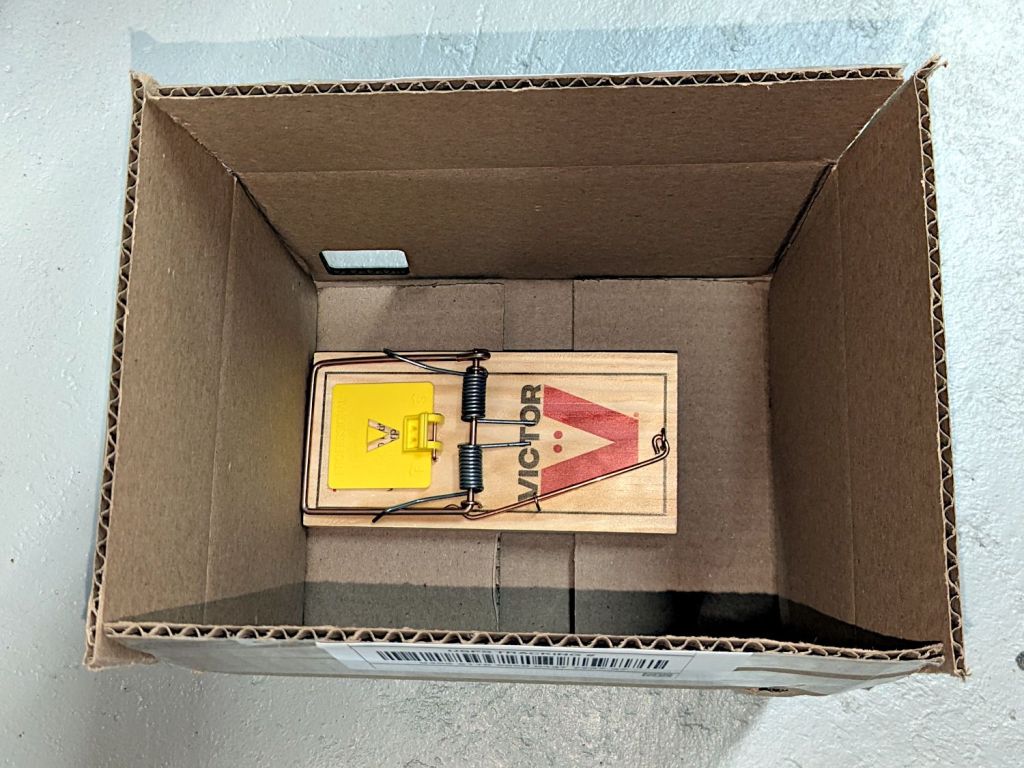

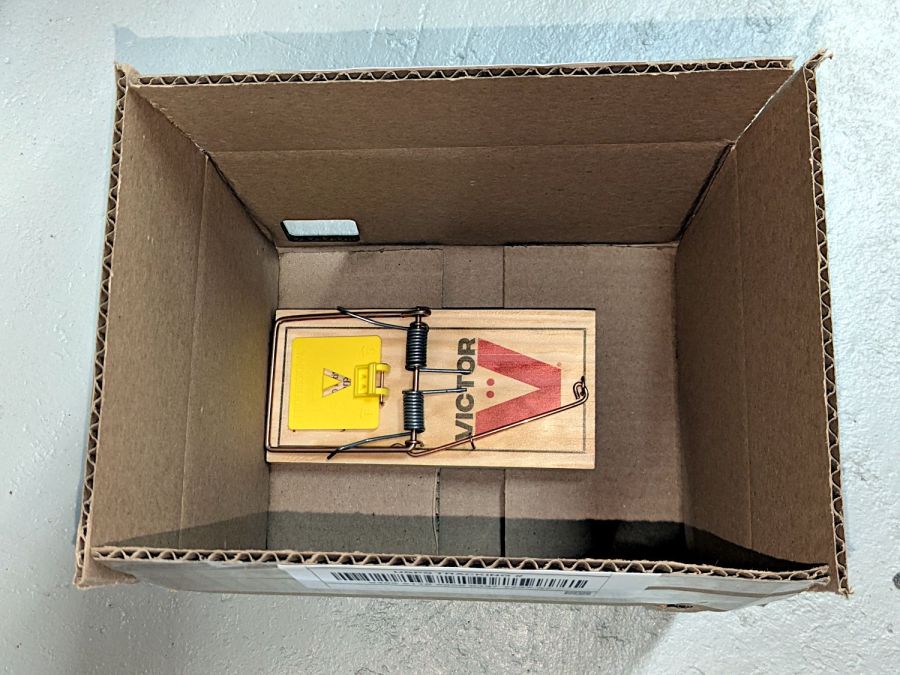

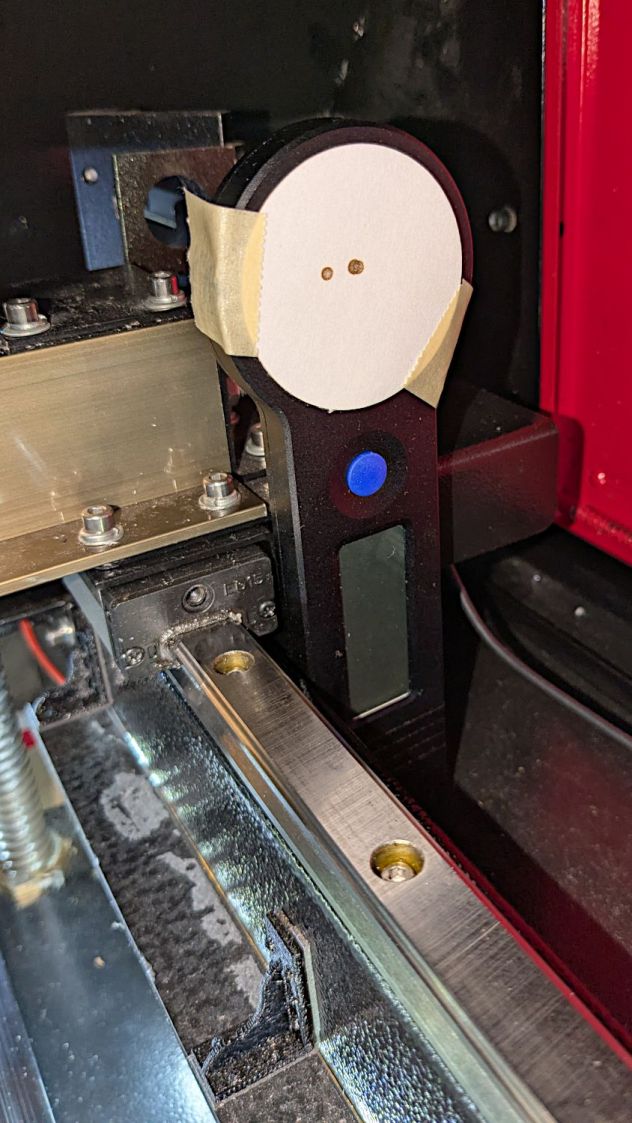

This clamp needs only one M6 screw into a square nut:

Again better seen in cross-section:

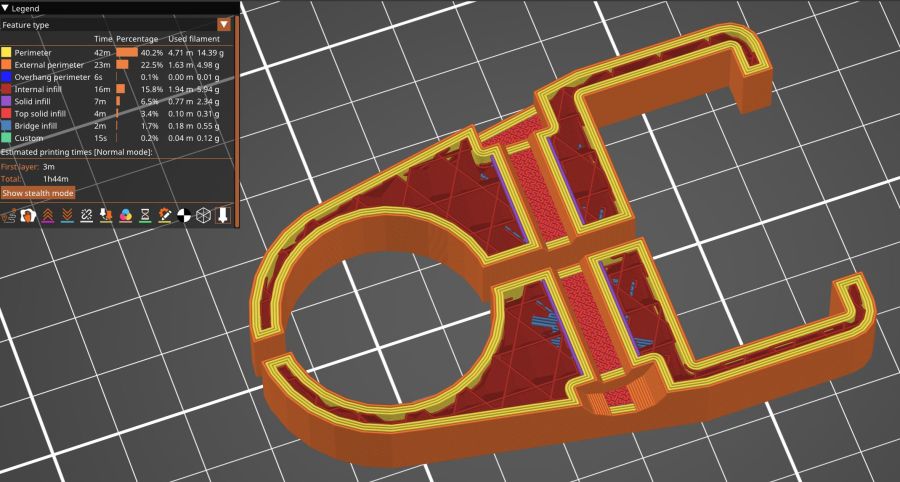

The OpenSCAD code extrudes the shape from a 2D arrangement, then punches the screw through the side:

// Monitor Pole box clamp

// Ed Nisley - KE4ZNU

// 2025-01-23

include <BOSL2/std.scad>

/* [Hidden] */

ID = 0;

OD = 1;

LENGTH = 2;

Protrusion = 0.1;

Box = [22.5,45.5,25.0]; // Z is clamp height

BoxGrip = 5.0; // on outer side clearing connectors

PoleOD = 30.5;

WallThick = 5.0;

Kerf = 3.0; // clamping space

Clearance = 2*0.2; // space around objects

Washer = [6.0,12.0,1.5]; // M6 washer

Nut = [6.0,10.0,5.0]; // M6 square nut

MidSpace = 35.0; // pole to box spacing

ClampOAL = Box.x + MidSpace + PoleOD + 2*WallThick;

//----------

// Build it

difference() {

linear_extrude(height=Box.z,convexity=5)

difference() {

hull() {

right(MidSpace/2 + Box.x/2)

rect(Box + 2*[WallThick,WallThick],rounding=WallThick);

left(MidSpace/2 + PoleOD/2)

circle(d=PoleOD + 2*WallThick);

}

right(MidSpace/2 + Box.x/2)

square(Box + [Clearance,Clearance],center=true);

right(MidSpace/2 + Box.x)

square([Box.x,Box.y - 2*BoxGrip],center=true);

left(MidSpace/2 + PoleOD/2)

circle(d=PoleOD + Clearance);

square([2*ClampOAL,Kerf],center=true);

}

up(Box.z/2) {

xrot(90)

cylinder(d=Washer[ID] + Clearance,h=2*Box.y,center=true,$fn=6);

fwd(Box.y/2 - Washer[LENGTH])

xrot(90) zrot(180/12)

cylinder(d=Washer[OD] + Clearance,h=Box.y,center=false,$fn=12);

back(Box.y/2 + Nut[LENGTH]/2)

xrot(90)

cube([Nut[OD],Nut[OD],2*Nut[LENGTH]],center=true);

}

}

The alert reader will have noticed I didn’t peel the protective film off the hub, which tells you how fresh this whole lashup is.