Most analog projects will benefit from an adjustment knob; the notion of pressing those UP and DOWN arrows just doesn’t give that wonderful tactile feedback. These days “knob” means a rotary encoder with quadrature outputs and some software converting digital bits into an adjustment value.

Sounds scary, doesn’t it?

This is actually pretty simple for most microcontrollers and the Arduino in particular. The Arduino website has some doc on the subject, but it seems far too complicated for most projects.

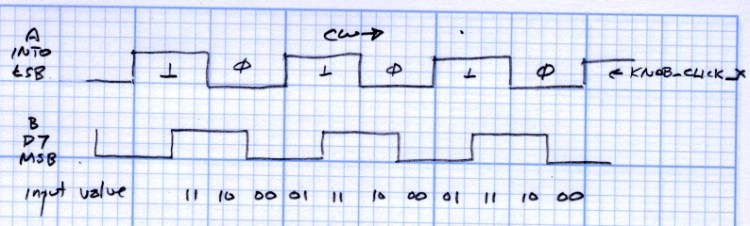

A quadrature rotary encoder has two digital outputs, hereinafter known as A and B. The cheap ones are mechanical switch contacts that connect to a common third terminal (call it C), the fancy ones are smooth optical interrupters. You pay your money and get your choice of slickness and precision (clicks per turn). I take what I get from the usual surplus sources: they’re just fine for the one-off projects I crank out most of the time.

How does quadrature encoding work?

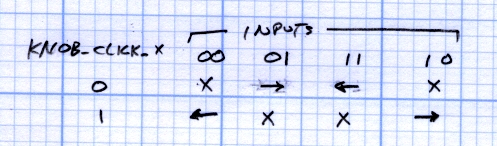

On each falling edge of the A signal, look at the B signal. If it’s HIGH, the knob has turned one click thataway. If it’s LOW, the knob has turned one click the other way. That’s all there is to it!

Here’s how you build a knob into your code…

Connect one of the outputs to an external interrupt, which means it goes to digital input D2 or D3 on the Arduino board. The former is INT0, the latter INT1, and if you need two interrupts for other parts of your project, then it gets a lot more complex than what you’ll see here. Let’s connect knob output A to pin D2.

Connect the other output, which we’ll call B, to the digital input of your choice. Let’s connect knob output B to D7.

Define the pins and the corresponding interrupt at the top of your program (yeah, in Arduino-speak that’s “sketch”, but it’s really a program):

#define PIN_KNOB_A 2 // digital input for knob clock (must be 2 or 3!))

#define IRQ_KNOB_A (PIN_KNOB_A - 2) // set IRQ from pin

#define PIN_KNOB_B 7 // digital input for knob quadrature

The external circuitry depends on whether you have a cheap knob or fancy encoder. Assuming you have a cheap knob with mechanical contacts, the C contact goes to circuit common (a.k.a, “ground”). If you have a fancy knob with actual documentation, RTFM and do what it say.

The two inputs need resistors (“pullups”) connected to the supply voltage: when the contact is open, the pin sees a voltage at the power supply (“HIGH“), when it’s closed the voltage is near zero (“LOW“).

Ordinary digital inputs have an internal pullup resistor on the ATmega168 (or whatever the Arduino board uses) that will suffice for the B signal. Unfortunately, the external interrupt pins don’t have an internal pullup, so you must supply your own resistor. Something like 10 kΩ will work fine: one end to the power supply, the other to INT0 or INT1 as appropriate.

With the knob connected, set up the pins & interrupt in your setup() function:

attachInterrupt(IRQ_KNOB_A,KnobHandler,FALLING);

pinMode(PIN_KNOB_B,INPUT);

digitalWrite(PIN_KNOB_B,HIGH);

The first statement says that the interrupt handler will be called when the A signal changes from HIGH to LOW.

The Arduino idiom for enabling the chip’s internal pullup on a digital input pin is to define the pin as an input, then write a HIGH to it.

Set up a variable to accumulate the number of clicks since the last time:

volatile char KnobCounter = 0;

The volatile tells the compiler that somebody else (the interrupt handler or the main routine) may change the variable’s value without warning, so the value must be read from the variable every time it’s used.

The variable’s size depends on the number of counts per turn and the sluggishness of the routine consuming the counts; a char should suffice for all but the most pathological cases.

Define the handler for the knob interrupt:

void KnobHandler(void)

{

KnobCounter += (HIGH == digitalRead(PIN_KNOB_B)) ? 1 : -1;

}

KnobHandler executes on each falling edge of the A signal and either increments or decrements the counter depending on what it sees on the B signal. This is one of the few places where you can apply C’s ternary operator without feeling like a geek.

Define a variable that will hold the current value of the counter when you read it:

char KnobCountIs, Count;

Now you can fetch the count somewhere in your loop() routine:

noInterrupts();

KnobCountIs = KnobCounter; // fetch the knob value

KnobCounter = 0; // and indicate that we have it

interrupts();

Turning interrupts off while fetching-and-clearing KnobCounter probably isn’t necessary for a knob that will accumulate at most one count, but it’s vital for programs that must not lose a step.

Now you can use the value in KnobCountIs for whatever you like. The next time around the loop, you’ll fetch the count that’s accumulated since the previous sample.

Even if you RTFM, apply painstaking logic, and wire very carefully, there’s a 50% chance that the knob will turn the wrong way. In that case, change one of these:

- In the interrupt handler, change HIGH to LOW

- In the attachInterrupt() statement, change FALLING to RISING

There, now, wasn’t that easy? Three wires, a resistor, a dozen lines of code, and your project has a digital quadrature knob!

If you have a painfully slow main loop, the accumulated counts in KnobCounter could get large. In that case, this code will give you a rubber-band effect: the accumulated count can be big enough that when the knob starts turning in the other direction it’s just decreasing the count, not actually moving count to the other side of zero. Maybe you need some code in the interrupt handler to zero the count when the direction reverses?

But that’s in the nature of fine tuning… twiddle on!