A comment on yesterday’s post about quartz crystal measurements prompted me to destroy a crystal in the name of science…

The question is, what effect does exposing a crystal to the air have on its performance? I would have sworn it would never work right again, because it’s normally running in an inert atmosphere and maybe a partial vacuum. One measurement being worth a kilo-opinion, here’s what happened.

I picked random crystal from the bottom of the crystal box, based on it having a solder seal that I could dismantle without deploying an abrasive cutoff wheel or writing some G-Code to slice the can off with a slitting saw. The crystal was labeled HCI-1800 18.000 MHz and probably older than most of the folks who will eventually read this… younger than some of us, though.

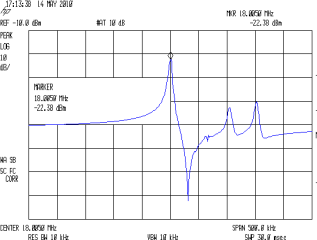

The overall response, measured in the same fixture as shown yesterday (click the pix for more detail):

The center frequency is 18.0050 MHz (at this rather broad span) and it has some ugly spurs out there to the right.

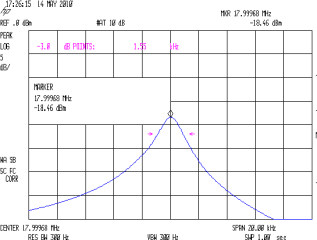

A closeup of the series-resonant peak:

The bandwidth is 1.50 kHz at 17.99950 MHz at this span.

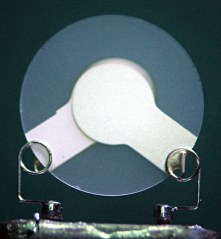

Then I applied a soldering iron around the seal and yanked the case off. I think that didn’t involve whacking the crystal with the case en passant, but I can’t be sure. In any event, it looks undamaged and seems to operate properly.

A pair of spring clips attach to the electrodes and hold the quartz disk in position. They’re just the cutest little things and quite unlike the other holders I’ve seen. I think the solder blobs fasten the spring ends together and don’t bond to the electrodes, but what do I know?

The quartz disk has a few small chips near the edge:

I think those are Inherent Vice… simply because:

- They’re not in a position where I could have whacked the disk and

- I doubt I could whack it that delicately

Anyhow, with the can off, here’s what the series resonant peak looks like:

The resonant frequency is now 17.99968, 180 Hz higher, which may be due to instability in the HP8591 spectrum analyzer’s not-stabilized-for-ten-hours ovenized oscillator. The bandwidth is 1.55 kHz, 50 Hz wider, although I think that’s one resolution quantum of difference.

Here are the two bandwidth traces overlaid.

The peak has been centered in both, so you can’t tell they’re slightly different. The interesting point is the difference in the slope to the low-frequency side of the peak, which is slightly higher for the open-case condition. Seeing as how the missing case completely changes the usual stray capacitance situation, I’m not surprised.

Anyhow, I admit to being surprised: there’s not that much difference after opening the case. I’ll put the naked crystal in a small container in a nominally safe place for a while, then retest it to see what’s happening.

Memo to Self: A “safe place” is nowhere near the Electronics Workbench!

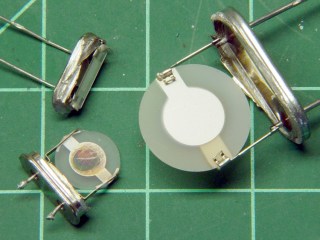

Here are some other naked crystals:

Notice the tarnished (presumably) silver electrodes on the crystal in the lower left. That one’s been sitting on my monitor and in other hazardous locations for a few years. I can’t find these anywhere right now, but if they turn up I’ll test them, too.