The main loop of the LED Curve Tracer firmware waits for a button push, then steps the LED current upward in 5 mA increments, measures a bunch of voltages, and prints the results in the tired old CSV format that feeds into Gnuplot and spreadsheets like nothing else.

The output looks thuslike:

# LED Curve Tracer

# Ed Nisley - KE4ZNU - July 2012

# VCC at LED: 4872 mV

# Bandgap reference voltage: 1039 mV

# Insert LED, press button 1 to start...

# INOM ILED VccLED VD VLED VG VS VGS VDS <--- LED 1

0 0 4867 3697 1169 0 0 0 3697

5 4585 4867 3013 1853 1959 48 1911 2965

10 9628 4867 2970 1896 2075 101 1973 2869

15 14672 4867 2917 1949 2166 154 2012 2763

20 20174 4867 2898 1969 2282 211 2070 2686

25 25218 4867 2883 1983 2339 264 2075 2619

30 30262 4867 2864 2002 2407 317 2089 2546

35 34847 4867 2850 2017 2498 365 2132 2484

40 40349 4867 2835 2031 2546 423 2123 2412

45 45393 4867 2821 2046 2614 476 2137 2344

50 49978 4872 2826 2046 2657 524 2132 2301

55 54563 4872 2811 2060 2729 572 2156 2238

60 60066 4872 2802 2070 2792 630 2161 2171

65 64651 4867 2792 2075 2874 678 2195 2113

70 69694 4867 2792 2075 2922 731 2190 2060

75 75197 4867 2777 2089 3004 789 2214 1988

# Insert LED, press button 1 to start...

I suppose calling it a “curve tracer” isn’t quite accurate, because the graphs actually come from the plotting software. Feel free to add one of those gorgeous color LCD panels and draw curves on the fly.

The code includes a constant for the measured VCC voltage from the regulator on the board, which is not, in general, ever the 5.000 V you expect. This will vary from board to board, so don’t kvetch if you get the wrong results without changing the constant. I assume that the analog reference voltage is just about exactly equal to the supply voltage, because I can’t measure it any more accurately.

Measuring VCC, however, calibrates all the other voltages, including the LED supply regulator and the bandgap.

Just for fun, the code measures & reports the 1.1 V bandgap reference voltage, which works out to be a bit on the low side at 1.039 V. That’s well within the hardware’s 10% tolerance spec, but no better than the usual power supply tolerance, so you must measure one or the other to get the right answer.

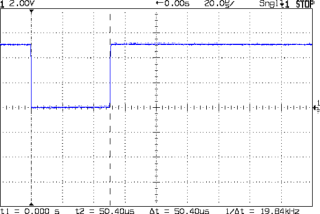

The Pro Mini board includes a cap on the analog reference pin, making it as quiet as it’ll get. The datasheet recommends an elaborate LC filter upstream of AVCC that nobody uses and there’s no room for, but it doesn’t really matter for this purpose.

The function that adjusts the gate voltage to produce a given LED current includes a bailout test to make sure the MOSFET drain-to-source voltage doesn’t drop too low. That happens with blue or violet LEDs (or, maybe white LEDs, which have a similar chemistry) at high currents, where the forward drop exceeds 4 V. There’s not enough headroom between the +5 V LED supply and the 10.5 Ω sense resistor, but the LED supply can’t exceed 5 V because we’re using the Arduino’s internal ADC and that’s limited to the supply voltage.

The Arduino source code:

// LED Curve Tracer

// Ed Nisley - KE4ANU - July 2012

#include <stdio.h>

//----------

// Pin assignments

const byte PIN_READ_LEDSUPPLY = 0; // AI - LED supply voltage blue

const byte PIN_READ_VDRAIN = 1; // AI - drain voltage red

const byte PIN_READ_VSOURCE = 2; // AI - source voltage orange

const byte PIN_READ_VGATE = 3; // AI - VGS after filtering violet

const byte PIN_SET_VGATE = 11; // PWM - gate voltage brown

const byte PIN_BUTTON1 = 8; // DI - button to start tests green

const byte PIN_BUTTON2 = 7; // DI - button for options yellow

const byte PIN_HEARTBEAT = 13; // DO - Arduino LED

const byte PIN_SYNC = 2; // DO - scope sync output

//----------

// Constants

const int MaxCurrent = 75; // maximum LED current - mA

const float Vcc = 4.930; // Arduino supply -- must be measured!

const float RSense = 10.500; // current sense resistor

const float ITolerance = 0.0005; // current setpoint tolerance

const float VGStep = 0.019; // increment/decrement VGate = 5 V / 256

const byte PWM_Settle = 5; // PWM settling time ms

#define TCCRxB 0x01 // Timer prescaler = 1:1 for 32 kHz PWM

#define MK_UL(fl,sc) ((unsigned long)((fl)*(sc)))

#define MK_U(fl,sc) ((unsigned int)((fl)*(sc)))

//----------

// Globals

float AVRef1V1; // 1.1 V bandgap reference - calculated from Vcc

float VccLED; // LED high-side supply

float VDrain; // MOSFET terminal voltages

float VSource;

float VGate;

unsigned int TestNum = 1;

long unsigned long MillisNow;

//-- Read AI channel

// averages several readings to improve noise performance

// returns value in mV assuming VCC ref voltage

#define NUM_T_SAMPLES 10

float ReadAI(byte PinNum) {

word RawAverage;

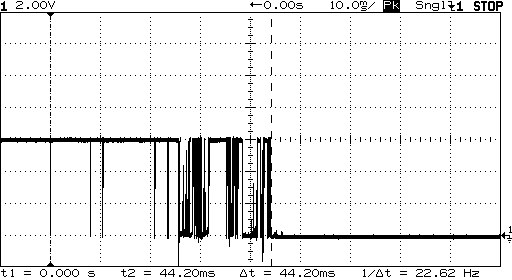

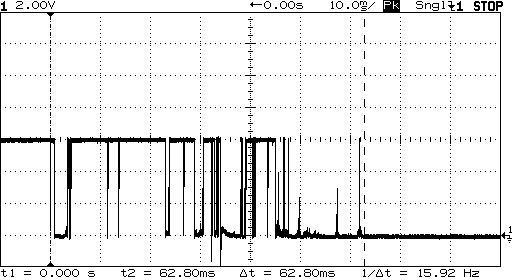

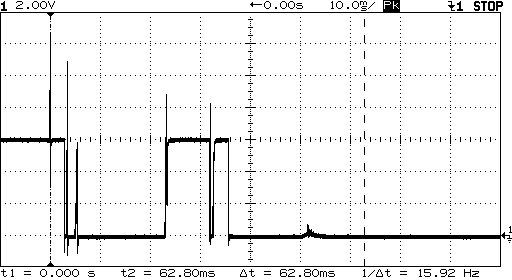

digitalWrite(PIN_SYNC,HIGH); // scope sync

RawAverage = analogRead(PinNum); // prime the averaging pump

for (int i=2; i <= NUM_T_SAMPLES; i++) {

RawAverage += (word)analogRead(PinNum);

}

digitalWrite(PIN_SYNC,LOW);

RawAverage /= NUM_T_SAMPLES;

return Vcc * (float)RawAverage / 1024.0;

}

//-- Set PWM output

void SetPWMVoltage(byte PinNum,float PWMVolt) {

byte PWM;

PWM = (byte)(PWMVolt / Vcc * 255.0);

analogWrite(PinNum,PWM);

delay(PWM_Settle);

}

//-- Set VGS to produce desired LED current

// bails out if VDS drops below a sensible value

void SetLEDCurrent(float ITarget) {

float ISense; // measured current

float VGateSet; // output voltage setpoint

float IError; // (actual - desired) current

VGate = ReadAI(PIN_READ_VGATE); // get gate voltage

VGateSet = VGate; // because input may not match output

do {

VSource = ReadAI(PIN_READ_VSOURCE);

ISense = VSource / RSense; // get LED current

// printf("\nITarget: %lu mA",MK_UL(ITarget,1000.0));

IError = ISense - ITarget;

// printf("\nISense: %d mA VGateSet: %d mV VGate %d IError %d mA",

// MK_U(ISense,1000.0),

// MK_U(VGateSet,1000.0),

// MK_U(VGate,1000.0),

// MK_U(IError,1000.0));

if (IError < -ITolerance) {

VGateSet += VGStep;

// Serial.print('+');

}

else if (IError > ITolerance) {

VGateSet -= VGStep;

// Serial.print('-');

}

VGateSet = constrain(VGateSet,0.0,Vcc);

SetPWMVoltage(PIN_SET_VGATE,VGateSet);

VDrain = ReadAI(PIN_READ_VDRAIN); // sample these for the main loop

VGate = ReadAI(PIN_READ_VGATE);

VccLED = ReadAI(PIN_READ_LEDSUPPLY);

if ((VDrain - VSource) < 0.020) { // bail if VDS gets too low

printf("# VDS=%d too low, bailing\n",MK_U(VDrain - VSource,1000.0));

break;

}

} while (abs(IError) > ITolerance);

// Serial.println("# Done");

}

//-- compute actual 1.1 V bandgap reference based on known VCC = AVcc (more or less)

// adapted from http://code.google.com/p/tinkerit/wiki/SecretVoltmeter

float ReadBandGap(void) {

word ADCBits;

float VBandGap;

ADMUX = _BV(REFS0) | _BV(MUX3) | _BV(MUX2) | _BV(MUX1); // select 1.1 V input

delay(2); // Wait for Vref to settle

ADCSRA |= _BV(ADSC); // Convert

while (bit_is_set(ADCSRA,ADSC));

ADCBits = ADCL;

ADCBits |= ADCH<<8;

VBandGap = Vcc * (float)ADCBits / 1024.0;

return VBandGap;

}

//-- Print message, wait for a given button press

void WaitButton(int Button,char *pMsg) {

printf("# %s",pMsg);

while(HIGH == digitalRead(Button)) {

delay(100);

digitalWrite(PIN_HEARTBEAT,!digitalRead(PIN_HEARTBEAT));

}

delay(50); // wait for bounce to settle

digitalWrite(PIN_HEARTBEAT,LOW);

}

//-- Helper routine for printf()

int s_putc(char c, FILE *t) {

Serial.write(c);

}

//------------------

// Set things up

void setup() {

pinMode(PIN_HEARTBEAT,OUTPUT);

digitalWrite(PIN_HEARTBEAT,LOW); // show we arrived

pinMode(PIN_SYNC,OUTPUT);

digitalWrite(PIN_SYNC,LOW); // show we arrived

TCCR1B = TCCRxB; // set frequency for PWM 9 & 10

TCCR2B = TCCRxB; // set frequency for PWM 3 & 11

pinMode(PIN_SET_VGATE,OUTPUT);

analogWrite(PIN_SET_VGATE,0); // force gate voltage = 0

pinMode(PIN_BUTTON1,INPUT_PULLUP); // use internal pullup for buttons

pinMode(PIN_BUTTON2,INPUT_PULLUP);

Serial.begin(9600);

fdevopen(&s_putc,0); // set up serial output for printf()

printf("# LED Curve Tracer\n# Ed Nisley - KE4ZNU - July 2012\n");

VccLED = ReadAI(PIN_READ_LEDSUPPLY);

printf("# VCC at LED: %d mV\n",MK_U(VccLED,1000.0));

AVRef1V1 = ReadBandGap(); // compute actual bandgap reference voltage

printf("# Bandgap reference voltage: %lu mV\n",MK_UL(AVRef1V1,1000.0));

Serial.println();

}

//------------------

// Run the test loop

void loop() {

WaitButton(PIN_BUTTON1,"Insert LED, press button 1 to start...\n");

printf("# INOM\tILED\tVccLED\tVD\tVLED\tVG\tVS\tVGS\tVDS\t<--- LED %d\n",TestNum++);

digitalWrite(PIN_HEARTBEAT,LOW);

for (int ILED=0; ILED <= MaxCurrent; ILED+=5) {

SetLEDCurrent(((float)ILED)/1000.0);

printf("%d\t%lu\t%d\t%d\t%d\t%d\t%d\t%d\t%d\n",

ILED,

MK_UL(VSource / RSense,1.0e6),

MK_U(VccLED,1000.0),

MK_U(VDrain,1000.0),

MK_U(VccLED - VDrain,1000.0),

MK_U(VGate,1000.0),

MK_U(VSource,1000.0),

MK_U(VGate - VSource,1000),

MK_U(VDrain - VSource,1000.0)

);

}

SetPWMVoltage(PIN_SET_VGATE,0.0);

}