-

Transformer Parameter Extraction & BH Curve Plotting

In addition to building a Spice model for a transformer, it’s also important to know whether the core can support the flux generated by the primary winding. This is similar to the inductor problem I mentioned there.

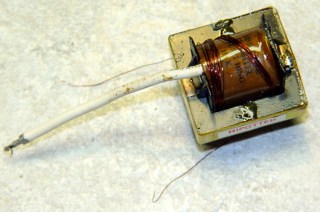

Small HV transformer with test winding Measure the core’s area and path length. One can reasonably expect all cores to have hard metric measurements these days: Yankees set those calipers to millimeters and get over it. Besides, you need metric units for everything that follows.

This transformer has two E-shaped core halves, so the center leg (the one with the windings on it) has twice the area of the outside legs, which are 7 mm thick and 5 mm wide. The central leg is twice that width: 10 mm.

Figure the stacking factor for a ferrite core is, oh, say, 0.9, making the effective core are:

Ac = 0.9 · 7 · 10 = 63 mm^2 = 0.63 cm^2

You need cm^2 here to get gauss later on.

The core is square, 30 mm on each side. Divide it in half, right down the middle of the center leg, then figure the mean path length around the middle of that rectangle:

MPL = 2 · (30 – 5) + 2 · (15 – 5) = 70 mm = 7 cm

Again, you need cm here to get oerstead down below.

Put a few turns Nt of fine wire around the core, outside all the other windings. This particular transformer has three small imperfections where the varnish / sealant didn’t quite bridge from the bobbin to the outer core legs, so I managed to sneak 20 turns of wire through the holes. Call this the test winding: Nt = 20.

Incidentally, that’s why you should always buy at least three units from surplus outlets: one to sacrifice, one to use, and one for a spare. I usually get five of anything.

Connect the transformer primary to a signal generator & oscilloscope Channel 1, connect the test winding to Channel 2, set the channels to maybe 100 mV/div. Set the signal generator for sine wave at maybe 1 kHz, crank on a few hundred millivolts, then read RMS voltages from both channels: Chan 1 = Vp, Chan 2 = Vt.

Knowing Vp and Vt and the number of turns Nt in the just-added extra winding, find the number of primary turns Np:

Vp / Vt = Np / Nt

136 / 40 = Np / 20

So Np = 68

Repeat that exercise, stuffing voltage into the transformer’s actual secondary winding (the HV winding):

4000 / 46 = Ns / 20

So Ns = 1739

Comfortingly, the turns ratio works out to what you’d expect from the voltage ratio measured while extracting those pi model parameters:

N = Np / Ns = 68 / 1739 = 0.039 = 1/25.6

(You may want the turns ratio as Ns/Np = 25.6. Either will work if you make the appropriate adjustments in the equations.)

Having measured the primary inductance as about 15 mH, the reactance at 60 Hz is:

5.6 Ω = 2 · π · 60 ·15e-3

So it’s reasonable to use a 100 mΩ current sensing resistor.

Plug a 6 VAC (not DC!) wall wart into the Variac and wire it to the primary through the resistor. Connect the oscilloscope X axis across the resistor, set the gain to maybe 10 mV/division.

Connect a 220 kΩ resistor in series with a 1 μF non-polarized capacitor, connect that to the normal HV secondary winding, connect the Y axis across the capacitor, set it for maybe 50 mV/div.

The capacitor voltage is the integral of the secondary voltage, scaled by 1/RC. The RC combination has a time constant of 220 ms, far longer than the 16.7 ms power-line period, so it’s a decent integrator.

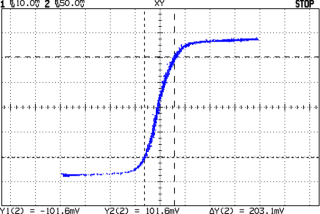

Small HV transformer BH curve Fire up the scope, set it for XY display, turn on the Variac, slowly crank up the voltage, and see something like this on the scope:

Tweak the offsets so the middle of the curve passes through the center of the graticule, maybe turn on the bandwidth limiting filters, adjust the gains as needed, then measure the point at the upper right at the end of the straightest section in the middle.

That point, as marked by the cursors, is more or less:

X = 6.5 mV

Y = 100 mV

Now plug all those numbers into the equations and turn the crank…

The magnetizing force H in oersteads:

H = (0.4 · π · Np · Ip) / MPL = (0.4 ·3.14 · 68 · Ip) / 7

H = 12.2 · Ip

Because the 100 mΩ current sensing resistor scales the current by 10 A/V, the scope X-axis calibration is:

H = 122 · Vsense

The core flux density B in gauss (noting that the turns is Ns and converting the peak Vcap voltage to RMS):

B =(0.707 · Vcap) · (R · C · 10^8) / (Ns · Ac) = Vcap · (220e3 ·1e-6 ·1e8) / (1739 · 0.63)

B = 14e3 · Vcap

Finally, at that point where the cursors meet in the upper right part of the curve:

H = 122 · 6.5e-3 = 0.8 Oe

B = 14e3 · 0.1 = 1400 G

Assuming there’s a straight line from the origin to that point (which is close to the truth), the B/H ratio gives the slope of the line and, thus, the core’s permeability:

µ = B / H = 1400 / 0.8 = 1700

It’s allegedly a ferrite core, so that’s in the right ballpark given the rough-and-ready approximations in the measurements.

The answer to the key question comes right off the scope without any fancy math, though. Just beyond the upper-right point the BH curve becomes horizontal, which means the slope is zero, which means the core is saturated, which means the circuit stops working.

Sooo, the maximum value of the primary current is pretty nearly:

Imax = 6.5 mV ·10 A/V = 65 mA

My back of the envelope for the high-voltage DC supply is that a peak of 30 mA will pretty much do the trick, so I’m in good shape. Might be a bit higher during startup, but it’ll sort itself out in short order.

Whew!

Correction: I did a total arithmetic faceplant in the previous version. I think this is now correct, but you should always cross-check anything you find on the InterWeb, fer shure!

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.